> Continued from Experiment for collaborative office space in Seoul (1)

The team discovered two issues for building a collaborative office space in Seoul.

- First, people have a double standard. They generally use the open space for serious reasons such as discussing business issues or having meetings with clients. However, when they notice others occupying the space, the others “seem to” chat over a cup of coffee, read casual books, or just have fun. This unnecessary strictness of others inhibits them from visiting the open space.

- Second, people prefer the sofas located next to the window over the white table located in the middle. This skewed flow does not allow accidental interactions.

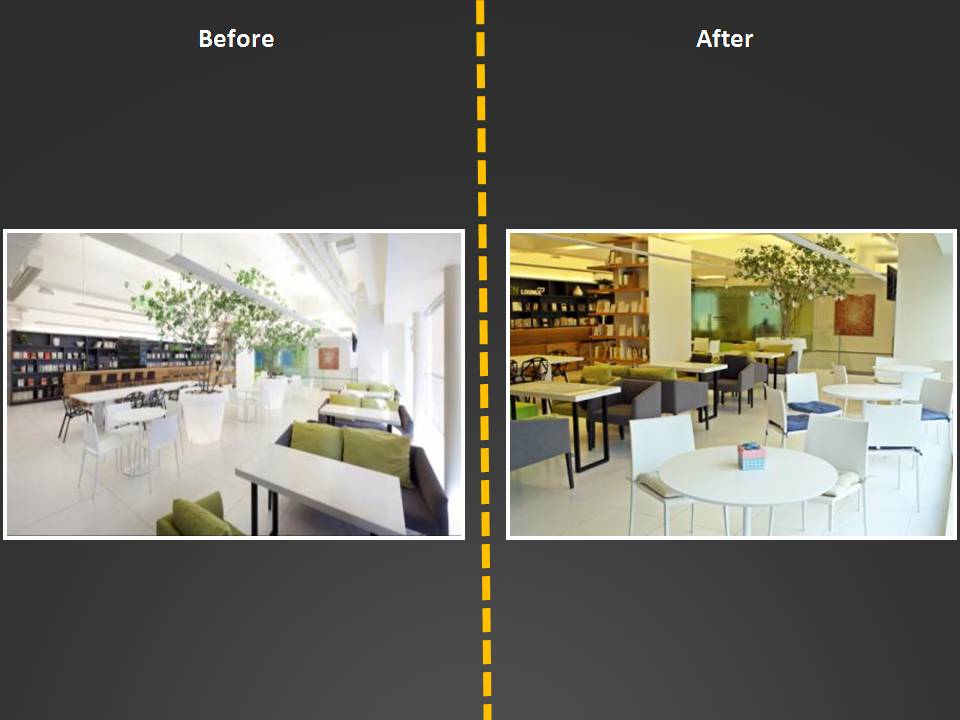

The team decided not to attack the first, psychological issue but to attack the second, technical issue and then conducted a few experiments to smooth the flow with a hope to make the whole space more vital. For example, the sofas and the round tables with chairs switched each other. As shown below, many people followed the sofas and while doing so, they made some accidental interactions, which is a key feature for collaborative office spaces (see Adam Alter’s post).

This project shows that a minor change in an office space determines the flow, which in turn makes the space where collaboration can happen.