I watched Tell Them We Were Here at the McMurtry Building at Stanford. It is a documentary about artists living and working in San Francisco.

One woman started by talking with prisoners. Later, she made a podcast called Ear Hustle with someone in prison. It won a Peabody Award.

One man has pushed a sewing machine on wheels through downtown San Francisco every month for 15 years. He mends clothes for free. He is not a tailor, but he wants to help.

One woman became known for drawing colorful lines. She gave her time and money to paint a big wall in San Francisco.

This 90-minute documentary made me stop and question. Why do these artists offer their talent so freely, expecting nothing in return? Am I overlooking something more meaningful that I should be pursuing?

As Melissa Kirsch wrote in The New York Times,

I often move between two minds, and lately this swing feels even more intense. When I attend AI seminars, efficiency becomes my top priority. When I speak with museum curators, I feel drawn to beauty or simply to helping others. Art and AI seem to sit at opposite ends of the spectrum.

**

Reference

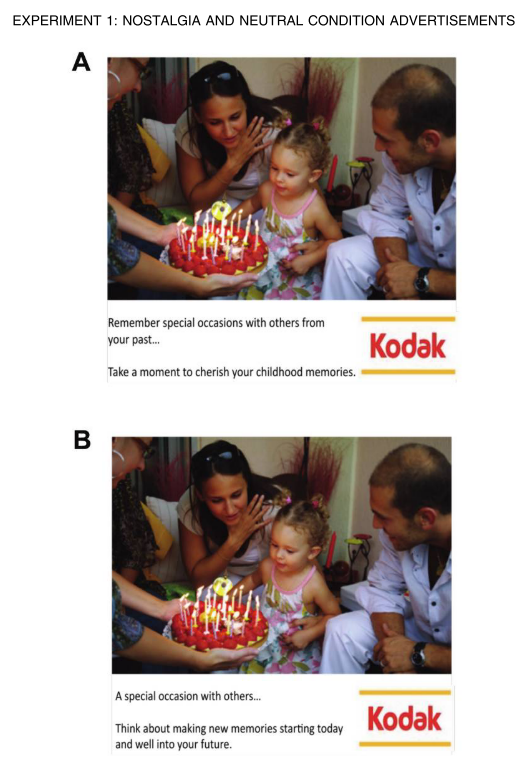

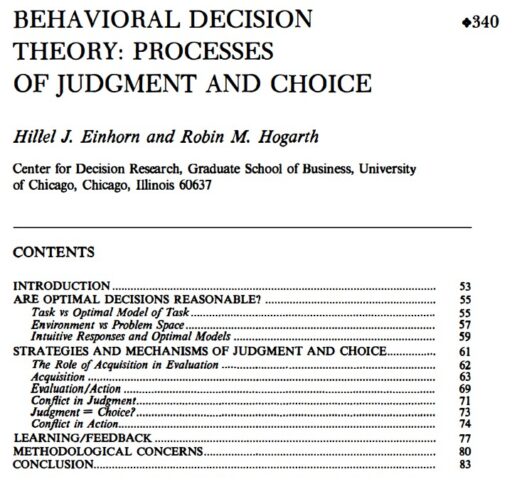

Lasaleta, J. D., Sedikides, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2014). Nostalgia Weakens the Desire for Money. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(3), 713–729.

Nostalgia has a strong presence in the marketing of goods and services. The current research asked whether its effectiveness is driven by its weakening of the desire for money. Six experiments demonstrated that feeling nostalgic decreased people’s desire for money. Using multiple operationalizations of desire for money, nostalgia (vs. neutral) condition participants were willing to pay more for products (experiment 1), parted with more money but not more time (experiment 2), valued money less (experiments 3 and 4), were willing to put less effort into obtaining money (experiment 5), and drew smaller coins (experiment 6). Process evidence indicated that nostalgia’s weakening of the desire for money was due to its capacity to foster social connectedness (experiments 5 and 6). Implications for price sen- sitivity, willingness to pay, consumer spending, and donation behavior are dis- cussed. Nostalgia may be so commonly used in marketing because it encourages consumers to part with their money.