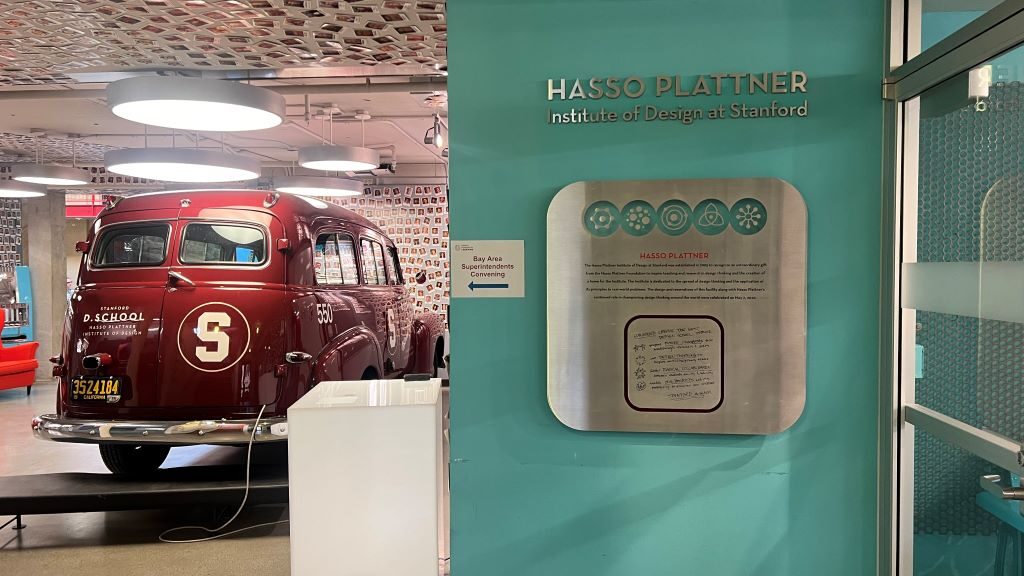

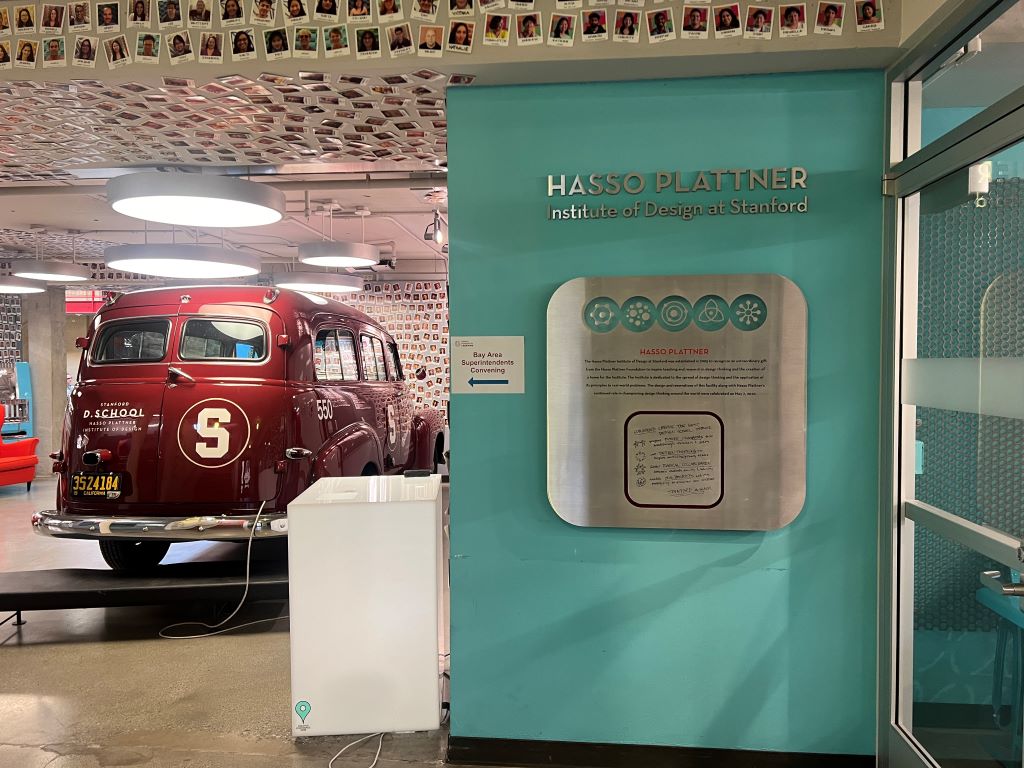

Stanford’s d.school workshop, Unleash Creativity, offers a unique hands-on approach to learning. During my visit, I could feel the creative energy, from the open second-floor view to the iconic d.school truck inside the building to the this year’s course schedule packed with hands-on activities.

In Unleash Creativity, participants jumped straight into exercises without explanation. For instance, instead of talking about ideas, they started by drawing, connecting, and coloring dots. The interesting part is that they only learned why they did each activity afterward, as the instructor, Dustin Liu, explained the purpose and effect. This approach—learning by doing—really made them feel the power of creative expression.

One memorable activity had them listen to others share about someone they admire and then draw that person without talking. This helped them see deeper into one another’s perspectives. Through the carefully designed powerful exercises of listening, sharing, and drawing, they experienced the true power of empathy.

***

Reference

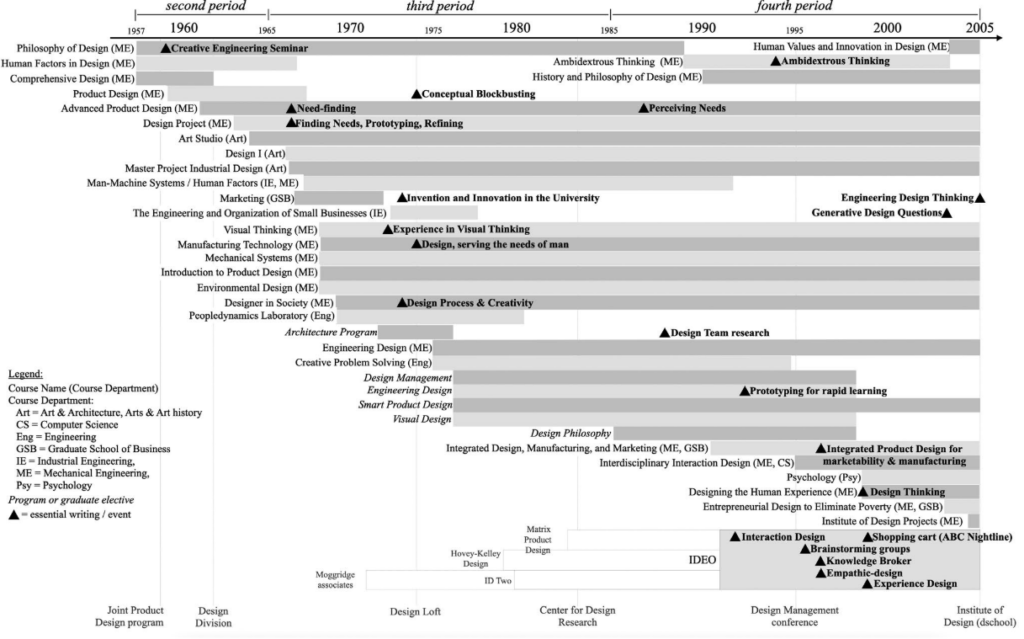

Auernhammer, J., & Roth, B. (2021). The origin and evolution of Stanford University’s design thinking: From product design to design thinking in innovation management. Journal of Product Innovation, 38(July), 623–644.

This article outlines the origin and evolution of one of the most influential design thinking perspectives in the Innovation Management discourse. This study addresses two significant criticisms of design thinking, namely, theoretical grounding and construct clarity. It also illustrates how this humanistic and creative design practice transcended into a comprehensive Innovation Management approach, facilitating entrepreneurship and innovation. Our research analyzes the evolution of the design philosophy and practices developed at Stanford University from 1957 to 2005 through document analysis. We identified design qualities that have been consistent over the decades, providing further construct clarity and insights on managing Design- driven Innovation. These design qualities elucidate design thinking as a cognitive process, creative practice, organizational routine, and design culture. They emphasize finding profound needs and problems and translate them into tangible designs, creating value for people. This design philosophy is deeply rooted in humanistic psychology theories, particularly on creativity and human values. Collaborations between psychologists, industrial researchers, and designers created this creative and human- centered design approach, known today as design thinking. This value- driven innovation offers a humanistic perspective on innovation theory and practice. It also offers an Innovation Management schema of design qualities essential for developing Design- driven Innovation capabilities in organizations and educational institutions. We emphasize that developing a creative design culture in which people have the human values, abilities, and confidence to collaboratively identify continuous emerging problems and needs and contribute through tangible designs generates an era of innovation and is essentially innovation management.

Practitioner Points

- Design thinking as a step-by-step process with tools prevents fluency in thinking and flexibility in approach, which are essential in Design-driven Innovation.

- An essential innovation management task is to develop a design culture and capabilities by freeing teams from emerging blocks imposed by the environment.

- In organizations, Design-driven Innovation requires the development of micro-foundation, such as abilities and attitudes & values, and capabilities, such as creative routines and environments of support and psychological safety and freedom.

- Innovation managers and educators need to consider essential design qualities when enabling people to design tangible solution for open and complex problems.