Barry Schwartz argues in his book, the Paradox of Choice, that increasing choices does not make us happy. Instead, reducing choices boosts sales and giving more options lowers choices.

Autonomy and Freedom of choice are critical to our well being, and choice is critical to freedom and autonomy. Nonetheless, though modern Americans have more choice than any group of people ever has before, and thus, presumably, more freedom and autonomy, we don’t seem to be benefiting from it psychologically. —quoted from Ch.5, The Paradox of Choice, 2004

Then, does giving more choices enhance the enjoyment choosers experience? It may not be, either. I had a similar experience at the cheese section of the Annam Gourmet at Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam. It provided a wide variety of cheeses. Therefore, spent a significant amount of time in carefully comparing multiple cheeses and eventually choosing one. When I tasted the selected cheese, unfortunately, I was confused which one to choose because I spent too much time on thinking about several cheeses.

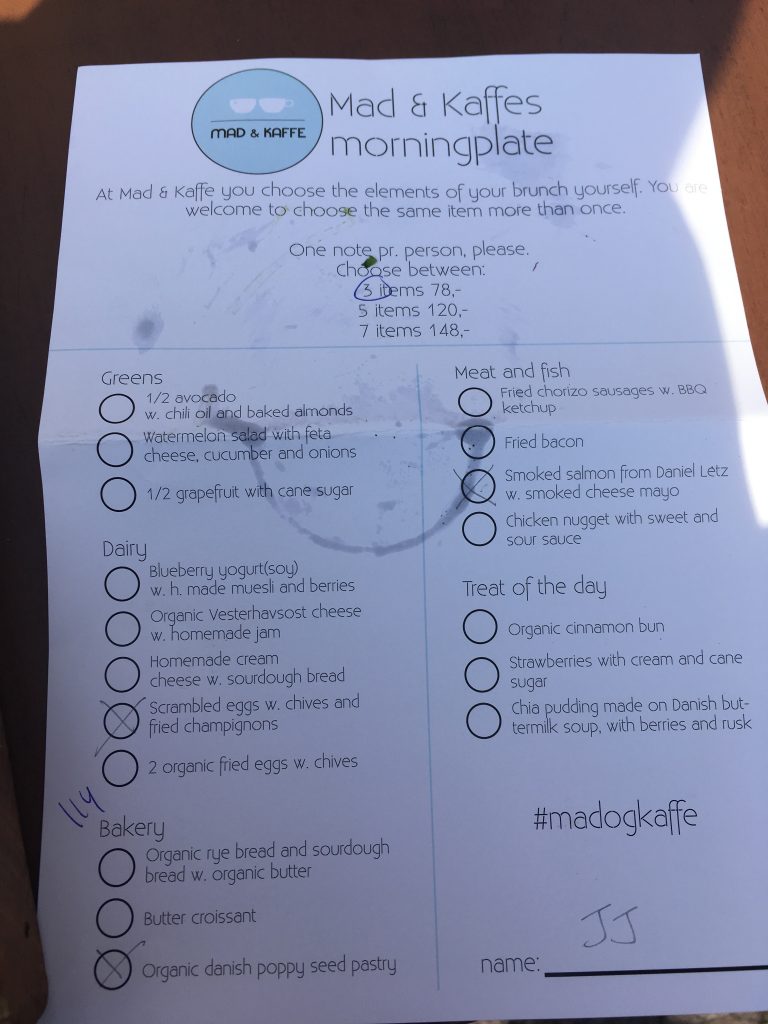

Then, what could marketers do to help people enjoy their experience? One suggestion is that when customers experience the option, they are reminded which one was chosen. For instance, if the option name is shown, customers will be able to keep focused on it.

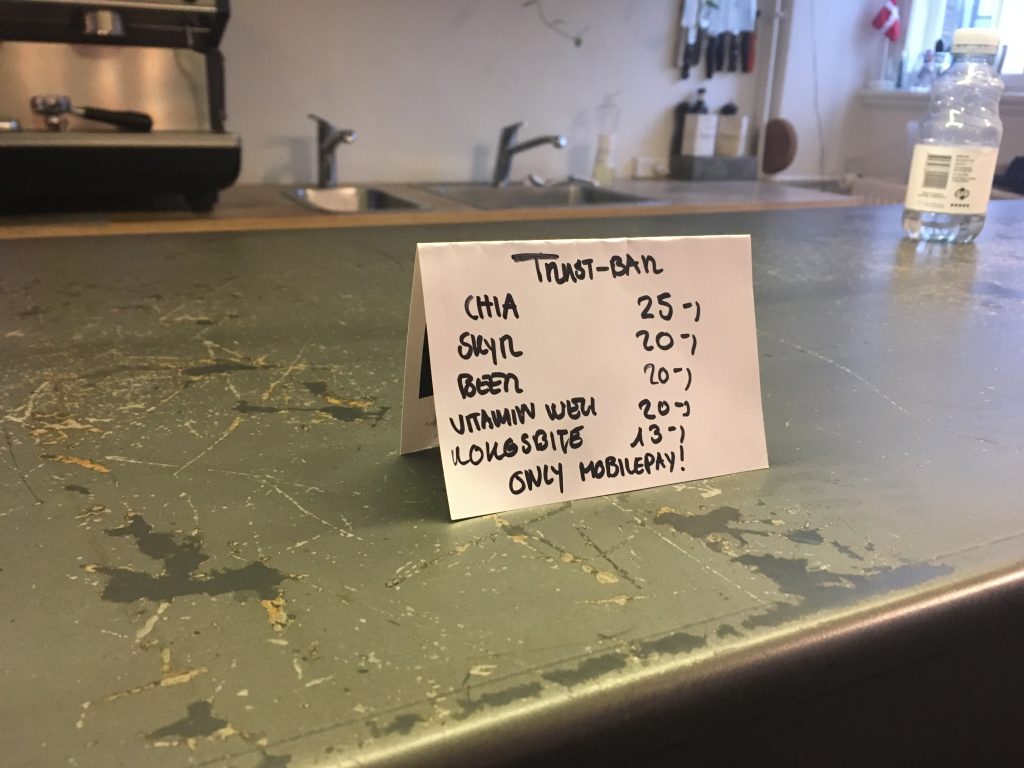

Nekkid Wings is a chicken wing restaurant in Seoul, Korea. Customers select one out of twelve flavors for a bucket of five wings. Some flavors are safe (e.g., classic buffalo) and others are risky (e.g., parmesan garlic). Most customers order multiple buckets and try safe and risky flavors together. The flavor names printed on the paper help customers focus on which flavor they are testing.

***

Reference

West, P. M., Brown, C. L., & Hoch, S. J. (1996). Consumption Vocabulary and Preference Formation. Journal of Consumer Research, 23(2), 120–135.

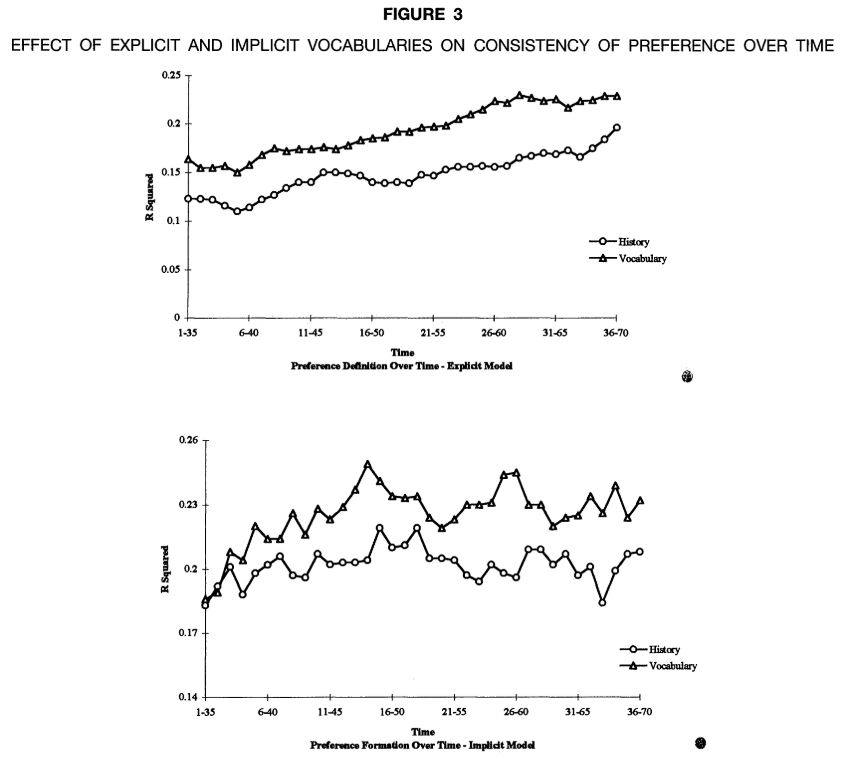

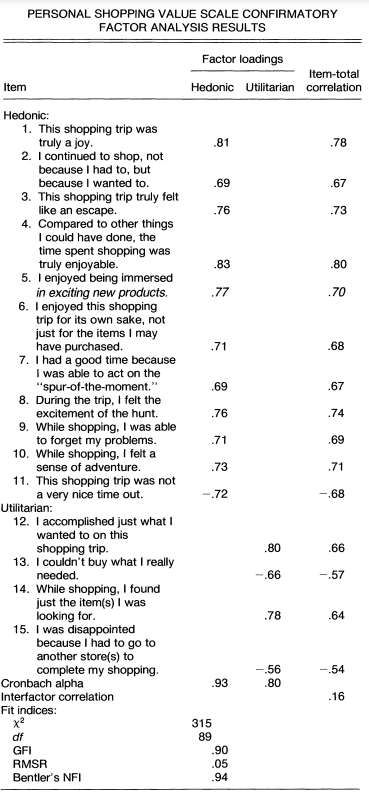

Consumers’ understanding of their own preferences can be aided by a “consumption vocabulary”—a taxonomy or framework that facilitates identifying the relation between a product’s features and one’s evaluation of the product. In the absence of such a vocabulary, consumers’ understanding of their own preferences will require more extensive experience and may never fully develop. The effect of such a vocabulary is tested in two experiments in which subjects provided with a vocabulary (1) exhibit better-defined and more consistent preferences than control subjects, (2) show improved cue discovery, and (3) show learning (i.e., increases in consistency over time). All results hold regardless of the functional form of the model used to assess subjects’ preference formation.