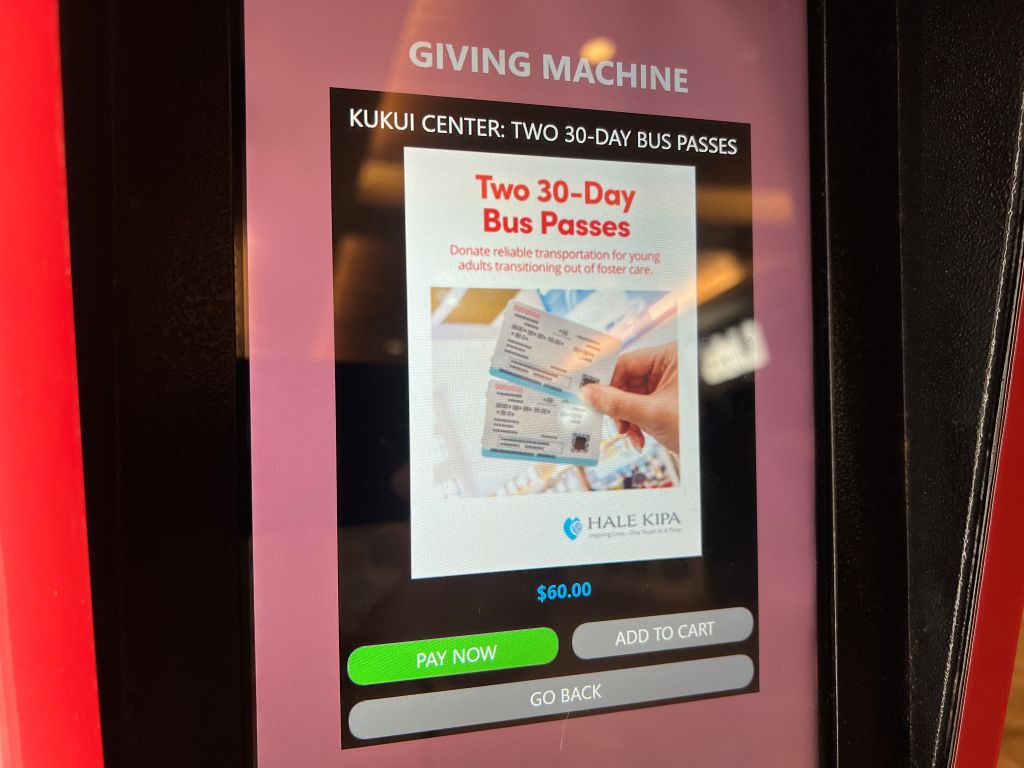

At the Ala Moana Shopping Center in Hawaii, a vending machine encourages donations. I do not know who designed this Giving Machine, but I am certain it is inspired by scientifically tested ideas in psychology and behavioral economics.

Before elaborating on three specific reasons, the key to its effectiveness lines in the vending machine itself. Unlike traditional charity appeals that vaguely describe where money goes, this machine allows donors see their choices clearly. The message on the machine also states: “100% of your donation goes to the charity cause of your choice.” This transparency reduces uncertainty.

However, visual clarity is just the beginning. Beyond visibility, three behavioral economics insights make this machine highly persuasive.

First, it offers multiple options, leveraging the power of choice. Donations range from $5 (sponsoring a meal) to $100 (after-school care). When presented with multiple options, people tend to focus more on the choice itself, making them more likely to choose at least one. By offering a structured selection, the machine nudges people toward making a donation rather than passing by.

Second, it shifts the decision from who to help to what to choose. Traditional charity appeals often focus on recipients such as disaster victims. This machine instead presents donors with tangible options such as bus passes, diapers, and hygiene kits, to name a few. This shift in framing nudges donors to engage more deeply by selecting specific solutions rather than simply reacting to an emotional appeal.

Third, the machine displays a pile of selected donations at the bottom. This is exactly an application of the goal-gradient hypothesis. People accelerate their efforts as they perceive themselves closer to a goal. Seeing donations accumulate creates an illusion of progress, encouraging more contributions.

A simple vending machine, yet a masterful execution of behavioral economics insights!

***

Reference 1

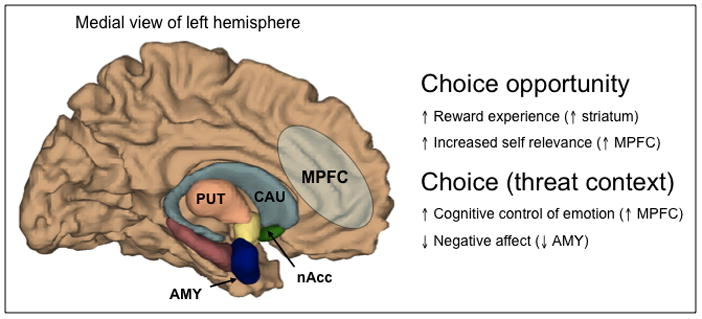

Leotti, L. A., Iyengar, S. S., & Ochsner, K. N. (2010). Born to choose: The origins and value of the need for control. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(10), 457-463.

Belief in one’s ability to exert control over the environment and to produce desired results is essential for an individual’s well-being. It has repeatedly been argued that perception of control is not only desirable, but is also probably a psychological and biological necessity. In this article, we review the literature supporting this claim and present evidence of a biological basis for the need for control and for choice—that is, the means by which we exercise control over the environment. Converging evidence from animal research, clinical studies, and neuroimaging suggests that the need for control is a biological imperative for survival, and a corticostriatal network is implicated as the neural substrate of this adaptive behavior.

***

Reference 2

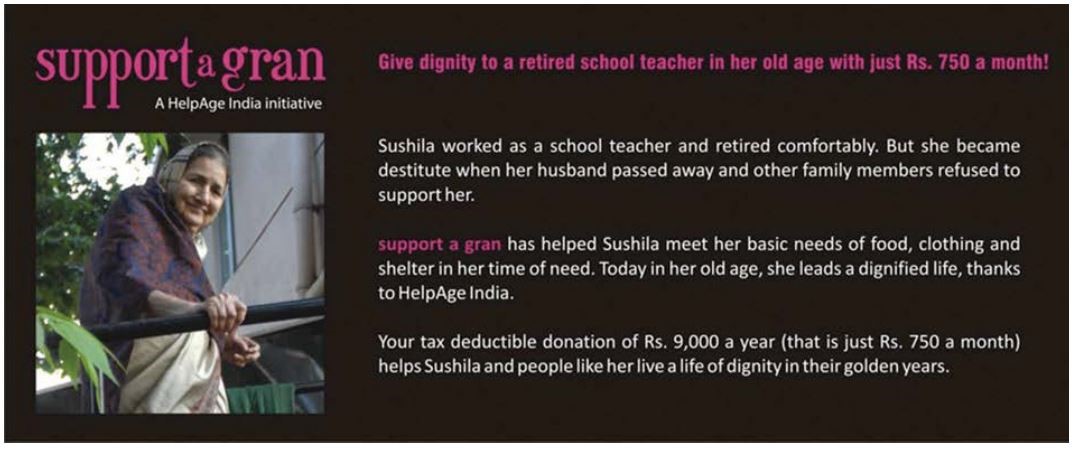

Sudhir, K., Roy, S., & Cherian, M. (2016). Do sympathy biases induce charitable giving? The effects of advertising content. Marketing Science, 35(6), 849-869.

We randomize advertising content motivated by the psychology literature on sympathy generation and framing effects in mailings to about 185,000 prospective new donors in India. We find a significant impact on the number of donors and amounts donated consistent with sympathy biases such as the “identifiable victim,” “in-group,” and “reference dependence.” A monthly reframing of the ask amount increases donors and the amount donated relative to daily reframing. A second field experiment targeted to past donors, finds that the effect of sympathy bias on giving is smaller in percentage terms but statistically and economically highly significant in terms of the magnitude of additional dollars raised. Methodologically, the paper complements the work of behavioral scholars by adopting an empirical researchers’ lens of measuring relative effect sizes and economic relevance of multiple behavioral theoretical constructs in the sympathy bias and charity domain within one field setting. Beyond the benefit of conceptual replications, the effect sizes provide guidance to managers on which behavioral theories are most managerially and economically relevant when developing advertising content.

***

Reference 3

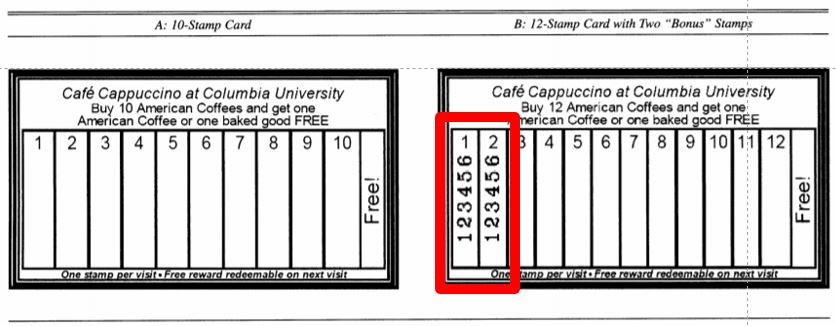

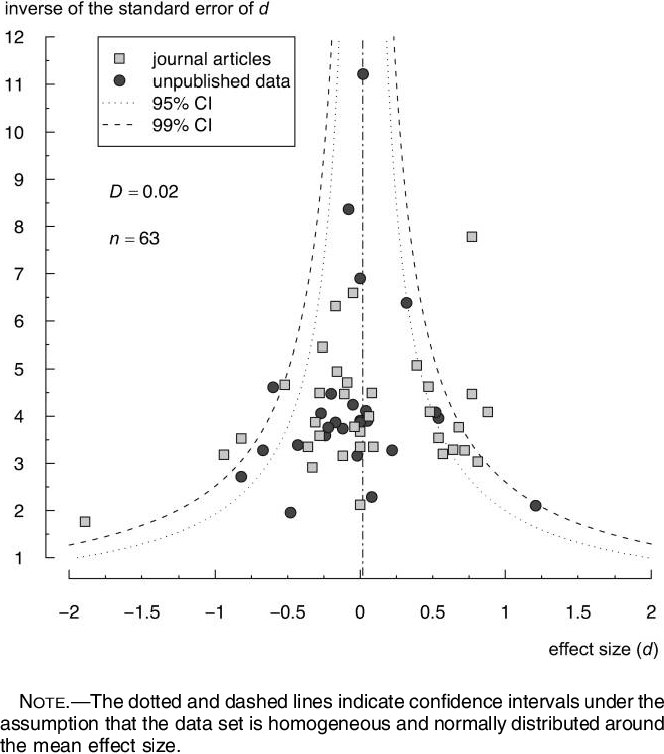

Kivetz, R., Urminsky, O., & Zheng, Y. (2006). The goal-gradient hypothesis resurrected: Purchase acceleration, illusionary goal progress, and customer retention. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(1), 39-58.

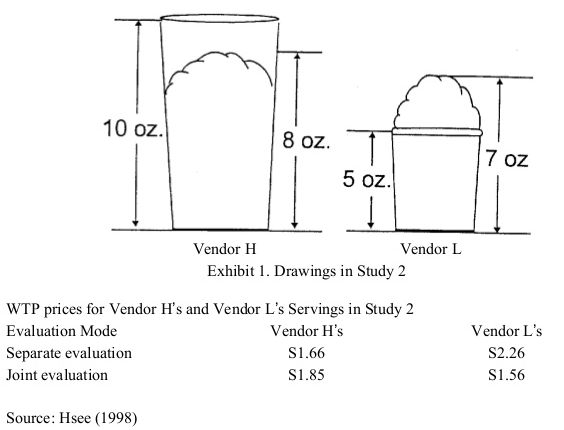

The goal-gradient hypothesis denotes the classic finding from behaviorism that animals expend more effort as they approach a reward. Building on this hypothesis, the authors generate new propositions for the human psychology of rewards. They test these propositions using field experiments, secondary customer data, paper-and-pencil problems, and Tobit and logit models. The key findings indicate that (1) participants in a real café reward program purchase coffee more frequently the closer they are to earning a free coffee; (2) Internet users who rate songs in return for reward certificates visit the rating Web site more often, rate more songs per visit, and persist longer in the rating effort as they approach the reward goal; (3) the illusion of progress toward the goal induces purchase acceleration (e.g., customers who receive a 12-stamp coffee card with 2 preexisting “bonus” stamps complete the 10 required purchases faster than customers who receive a “regular” 10-stamp card); and (4) a stronger tendency to accelerate toward the goal predicts greater retention and faster reengagement in the program. The conceptualization and empirical findings are captured by a parsimonious goal-distance model, in which effort investment is a function of the proportion of original distance remaining to the goal. In addition, using statistical and experimental controls, the authors rule out alternative explanations for the observed goal gradients. They discuss the theoretical significance of their findings and the managerial implications for incentive systems, promotions, and customer retention.