During my recent visit to the Farmers’ Market at the California Avenue, I met a unique and captivating fruit display by Sweet Tree Farms.

They presented six different fruits (lemon, apple, tangerine, pomegranate, pear, and orange) peeled, chopped, and neatly arranged in clean containers atop a bed of ice. Each container was paired with its whole fruit counterpart, visually comparing between the raw and prepared states of each fruit.

This creative presentation not only demonstrates the freshness of the fruits but also allows shoppers to imagine these fruits as part of their meals. It was shown that neatly organized and visually clear presentations increased consumers’ willingness to buy, at least, for some products.

***

Reference

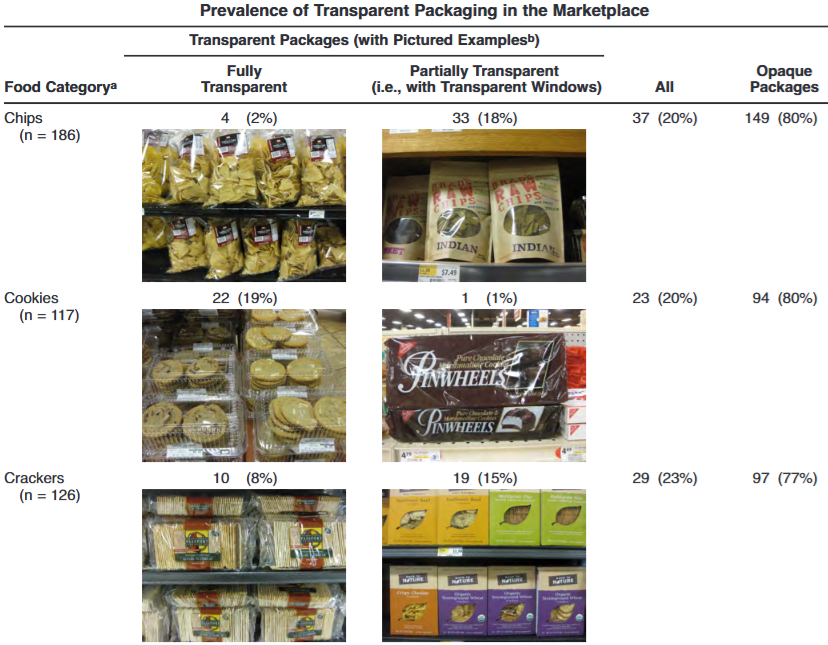

Deng, X., & Srinivasan, R. (2013). When do transparent packages increase (or decrease) food consumption?. Journal of Marketing, 77(4), 104-117.

Transparent packages are pervasive in food consumption environments. Yet prior research has not systematically examined whether and how transparent packaging affects food consumption. The authors propose that transparent packaging has two opposing effects on food consumption: it enhances food salience, which increases consumption (salience effect), and it facilitates consumption monitoring, which decreases consumption (monitoring effect). They argue that the net effect of transparent packaging on food consumption is moderated by food characteristics (e.g., unit size, appearance). For small, visually attractive foods, the monitoring effect is low, so the salience effect dominates, and people eat more from a transparent package than from an opaque package. For large foods, the monitoring effect dominates the salience effect, decreasing consumption. For vegetables, which are primarily consumed for their health benefits, consumption monitoring is not activated, so the salience effect dominates, which ironically decreases consumption. The authors’ findings suggest that marketers should offer small foods in transparent packages and large foods and vegetables in opaque packages to increase postpurchase consumption (and sales).