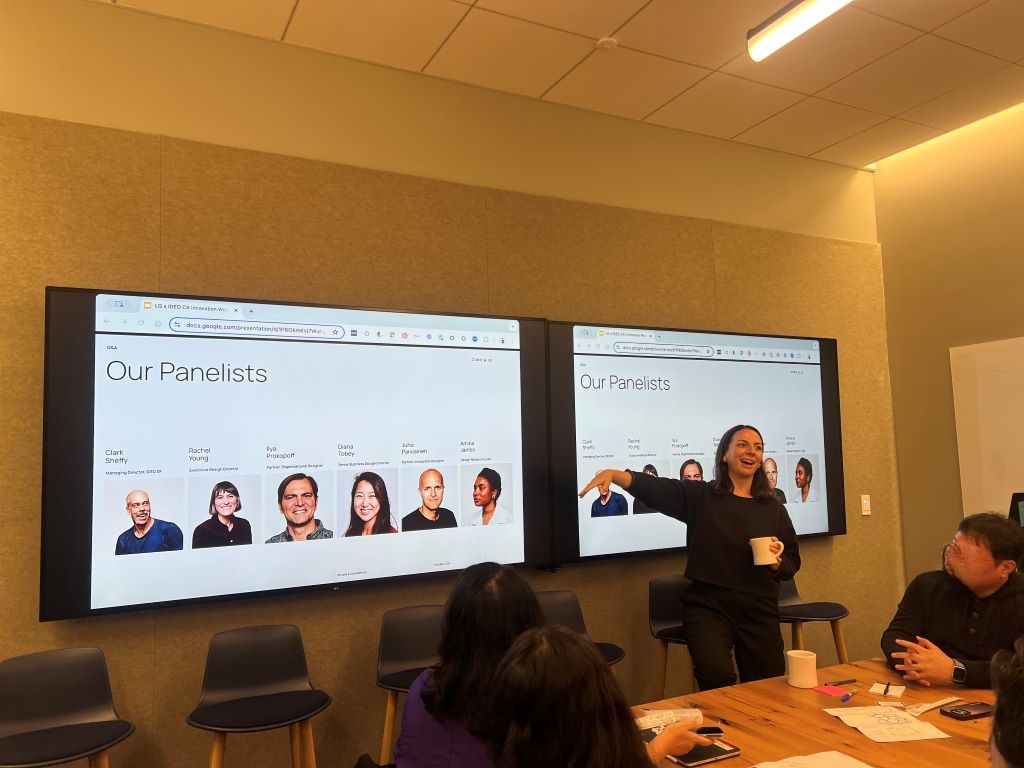

During a recent visit to IDEO‘s San Francisco office, I learned how design thinking can be harnessed in B2B contexts and the transformative potential of generative AI. IDEO’s approach highlighted how design thinking is not limited to extreme end-users but extends meaningfully to B2B industries. By embracing this methodology, companies can reduce development timelines while serving the needs of various stakeholders.

IDEO’s collaboration with Ford highlights how design thinking can adapt quickly to address B2B challenges. Ford identified a gap in van driver security due to the long product development cycles. In response, IDEO designed a van security solution within just 12 weeks, quick prototyping to expedite development. This solution ultimately led to the creation of the joint venture between Ford and ADT, which integrated sensors, cameras, and AI to detect window breakage or unauthorized access.

One particularly inspiring session was learning about the integration of generative AI into design thinking processes. Generative AI, such as ChatGPT, has opened new avenues for, so called, “synthetic research.” Generative AI enables the creation of hypothetical personas that bring fresh insight into understanding potential customer needs. Additionally, by using video prototypes developed through AI, designers can iterate on ideas faster and more creatively than traditional methods allow.

This visit enlightened me about the transformative potential of merging emerging technologies like generative AI with established design thinking frameworks. By continuously pushing the boundaries of design thinking, IDEO opens new possibilities for the B2B sector, fostering faster, tailored solutions to meet evolving needs.

***

Reference

Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard business review, 86(6), 84.

In the past, design has most often occurred fairly far downstream in the development process and has focused on making new products aesthetically attractive or enhancing brand perception through smart, evocative advertising. Today, as innovation’s terrain expands to encompass human-centered processes and services as well as products, companies are asking designers to create ideas rather than to simply dress them up.

Brown, the CEO and president of the innovation and design firm IDEO, is a leading proponent of design thinking—a method of meeting people’s needs and desires in a technologically feasible and strategically viable way. In this article he offers several intriguing examples of the discipline at work. One involves a collaboration between frontline employees from health care provider Kaiser Permanente and Brown’s firm to reengineer nursing-staff shift changes at four Kaiser hospitals. Close observation of actual shift changes, combined with brainstorming and rapid prototyping, produced new procedures and software that radically streamlined information exchange between shifts. The result was more time for nursing, better-informed patient care, and a happier nursing staff.

Another involves the Japanese bicycle components manufacturer Shimano, which worked with IDEO to learn why 90% of American adults don’t ride bikes. The interdisciplinary project team discovered that intimidating retail experiences, the complexity and cost of sophisticated bikes, and the danger of cycling on heavily trafficked roads had overshadowed people’s happy memories of childhood biking. So the team created a brand concept—“Coasting”—to describe a whole new category of biking and developed new in-store retailing strategies, a public relations campaign to identify safe places to cycle, and a reference design to inspire designers at the companies that went on to manufacture Coasting bikes.