At Oracle Park, I watched the San Francisco Giants play the San Diego Padres. Jung Hoo Lee, a former star in the Korean baseball league stole a second base that day.

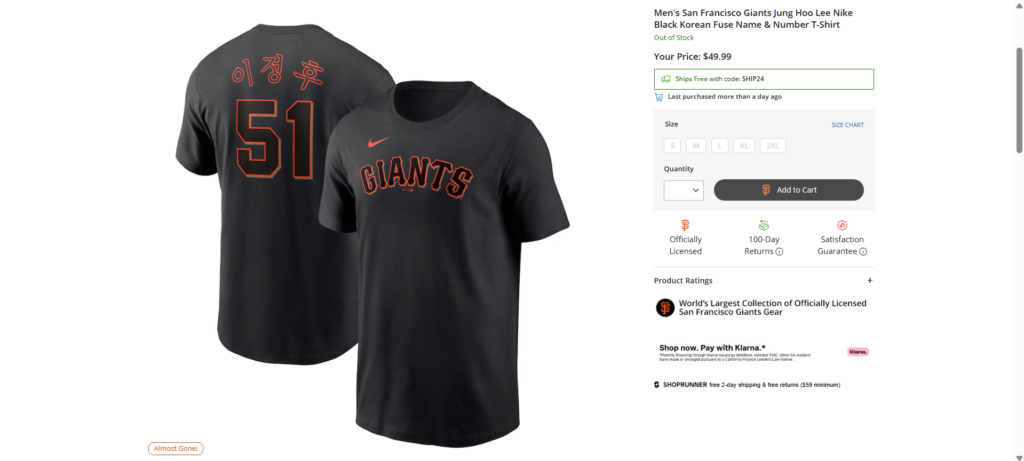

During a break in the game, I noticed a non-Korean person wearing a jersey with his name in Korean (이정후) printed in bold Korean letters on the back. It was not J. H. Lee.

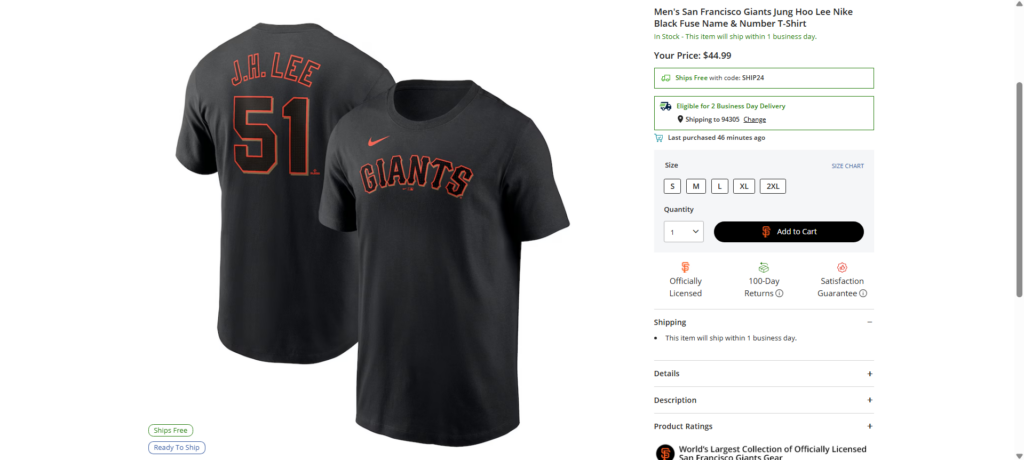

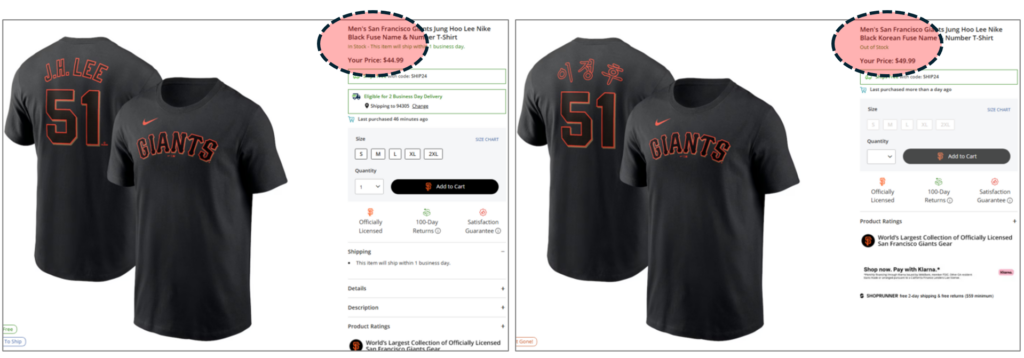

Later, back at home, I went to mlbshop.com out of curiosity. The official Nike t-shirt with “J. H. Lee” was priced at $44.99. But the same shirt, with “이정후” on the back, cost $49.99. It was five dollars more and sold out.

I checked the prices of other players’ shirts. Matt Chapman’s shirt also cost $44.99. Logan Webb’s was slightly cheaper at $39.99. Jorge Soler, who is no longer on the team, was listed for just $19.99. Among them, the version with Korean script was the most expensive.

From a marketing perspective, this price difference reflects the interesting psychology of fans. One reason could be uniqueness. Fans might want to be unique and choose the Korean version to feel rare. Another reason might be authenticity. Wearing the player’s name in his native language could feel more genuine. Finally, there might also be a sense of community. Wearing the Korean version might signal a shared cultural identity.

Fans often sacrifice convenience and pursue originality. They want to express identity, value, and/or a sense of belonging.

**

Reference

Smith, R. K., Vandellen, M. R., & Ton, L. A. N. (2021). Makeup who you are: Self-expression enhances the perceived authenticity and public promotion of beauty work. Journal of Consumer Research, 48(1), 102–122.

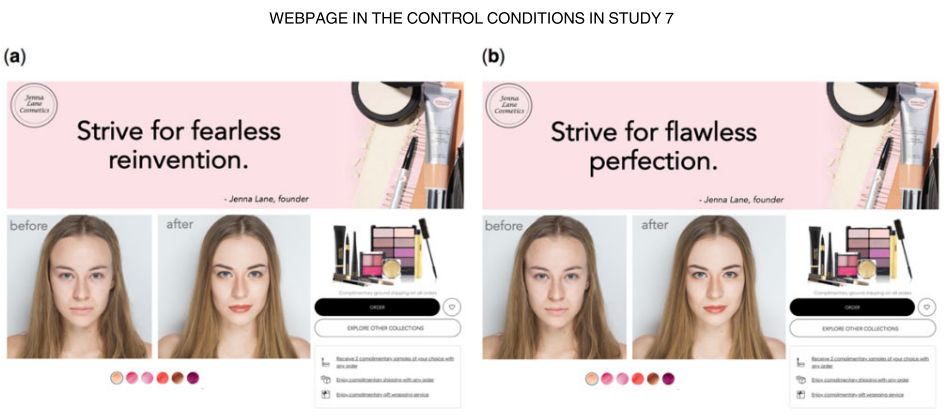

Although consumers put substantial effort toward their appearance, engaging in beauty work is often seen as inauthentic, posing challenges for beauty companies that increasingly rely on social media-driven product promotion where authenticity perceptions are consequential. This article draws on existentialist notions of authenticity (wherein the true self is created rather than innate) to explore how framing beauty work as self-expression alters others’ perceptions and, in turn, marketing outcomes. First, an archival analysis of Instagram posts demonstrates that rebranding beauty work as self-expression is positively associated with word-of-mouth about beauty products. Six studies then test how motivational information alters perceptions of people who engage in beauty work. Lowered authenticity perceptions arise from observers’ default assumption that beauty work is motivated by self-enhancement and serves primarily to conceal appearances. By contrast, self-expression enhances authenticity by leading others to see beauty work as a form of creation rather than concealment. This pattern extends to when people engage in a variety of beauty work transformations but not when beauty work is designed to restore appearances or is framed as connected to the innate self. These findings provide insight into judgments of authenticity and the management of a stigma associated with product use.