I drink wine often. It goes well with dinner, helps me read papers, and soothes me at night. In the past, I enjoyed numerous marriages of soil, weather, and grape variety. Now, my tongue is developed although I neither remember one nor am able to elaborate why I like one.

Recently, I went to Urban Break 2021 and saw a pop-up store of Babe Wine, a brand name of a canned wine. It attracted a crowd of visitors. Out of curiosity, I sampled a sip of Grigio, Rose, and Red. They differed from the wine I experienced before. They came out from icy-cold cans and had bubbles. I ended up failing to like this wine.

Despite of my disappointment, this canned wine attracts attention internationally. “From 2016-2020, BABE’s CAGR was nearly 2,000% according to IRI. These numbers quickly caught the eye of beverage giant Anheuser-Busch, who acquired Babe in 2019.” According to the article in Forbes, “Babe specifically focused on targeting the wine lover who cracked open bottles on the regular, but “couldn’t name a single brand,” says Ostrovsky.””

Why do people like a canned wine I do not? Indeed, I have a long history of prediction errors. On one hand, I once thought that BTS, Tiktok, and Instagram would fail to make a presence. On the other hand, I expected that Clubhouse, a social audio app, and Gathertown, a meta-verse service, would succeed in Korea. Not surprisingly, my predictions were proven to be incorrect.

Then, how could experts like me (e.g., wine lovers) predict whether a product is successful in the market when it is designed for novices (e.g., canned wine)? About 10 years ago, researchers at University of Oxford and New York University suggested that an accurate prediction of an extreme event is an indication of poor forecasting ability. This suggests that even experts who have forecasting abilities predict only non-radical events. Predicting the next hit is beyond our control.

***

Reference

Denrell, J., & Fang, C. (2010). Predicting the Next Big Thing: Success as a Signal of Poor Judgment. Management Science, 56(10), 1653–1667.

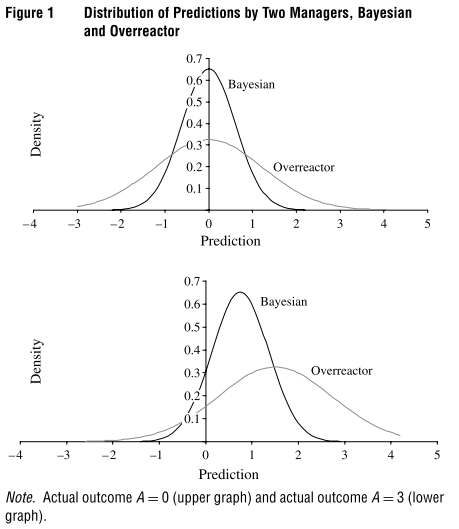

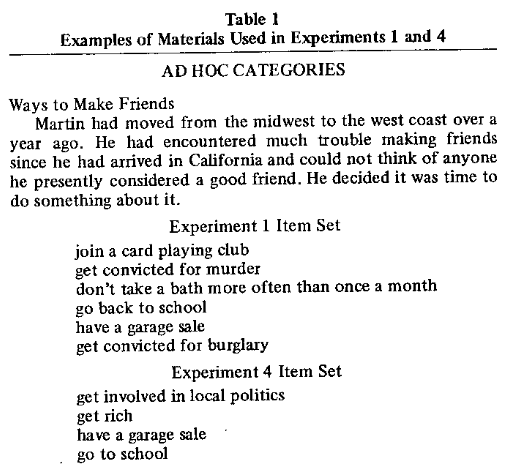

Successfully predicting that something will become a big hit seems impressive. Managers and entrepreneurs who have made successful predictions and have invested money on this basis are promoted, become rich, and may end up on the cover of business magazines. In this paper, we show that an accurate prediction about such an extreme event, e.g., a big hit, may in fact be an indication of poor rather than good forecasting ability. We first demonstrate how this conclusion can be derived from a formal model of forecasting. We then illustrate that the basic result is consistent with data from two lab experiments as well as field data on professional forecasts from the Wall Street Journal Survey of Economic Forecasts.