Yoon, Y., Deng, R., & Joo, J. (2022). The Effect of Marketing Activities on Web Search Volume: An Empirical Analysis of Chinese Film Industry Data. Applied Sciences, 12, 2143.

Abstract

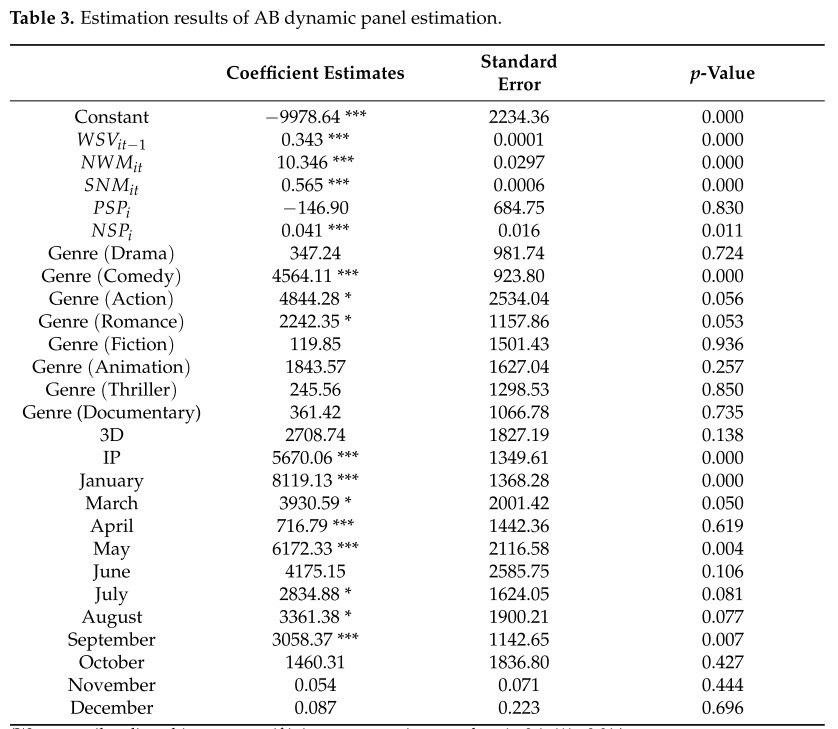

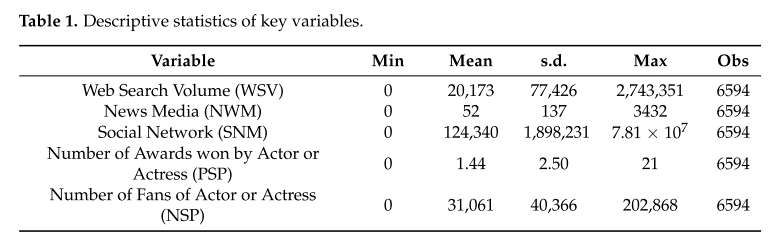

Prior research on consumers’ web searches primarily examined the effect of web searches on product sales or the characteristics of the web searchers. Differing from prior research, we investigate the effect of marketing activities on web search volume. We selected 314 movies released in China whose box office revenues were greater than RMB 10,000. Then, we collected data points on web search volume and marketing activities from the Baidu, Sina Weibo, and Douban platforms from the 3 weeks prior to the release of each movie. Marketing activity data points were derived from three sources: news media, social network marketing, and film stars. Our data analysis of 6594 observations revealed two major findings. First, news media, social network marketing, and the effect of film stars increased the web search volumes of the films. In particular, social network marketing had the strongest impact on the web search volume. Second, the previous‐day web search volume increased the present‐day web search volume without marketing activities, suggesting a spillover effect. We discuss the academic contributions and managerial implications of our findings in the context of online marketing and new product launches.

Keywords

web search behavior; film industry; news media; social network; star; new product