Rebecca Ackermann wrote “Design thinking was supposed to fix the world. Where did it go wrong? An approach that promised to democratize design may have done the opposite.” In this MIT Technology Review article, she claimed that design thinking disappointed us.

But in recent years, for a number of reasons, the shine of design thinking has been wearing off. Critics have argued that its short-term focus on novel and naive ideas has resulted in unrealistic and ungrounded recommendations. And they have maintained that by centering designers—mainly practitioners of corporate design within agencies—it has reinforced existing inequities rather than challenging them.

Although design thinking *process* rarely produces market-shaking products, design thinking *training* shakes the way people think. When carefully customized, it encourages engineers to be customer-centric and think outside the box. More details about how LG Academy customized a design thinking training is available upon request.

Bertao, R. A., Jung, C. H, Chung, J., and Joo, J. (2023), Design thinking: a customized blueprint to train R & D personnnel in creative problem solving., Thinking Skills and Creativity, 48, 101253.

Abstract

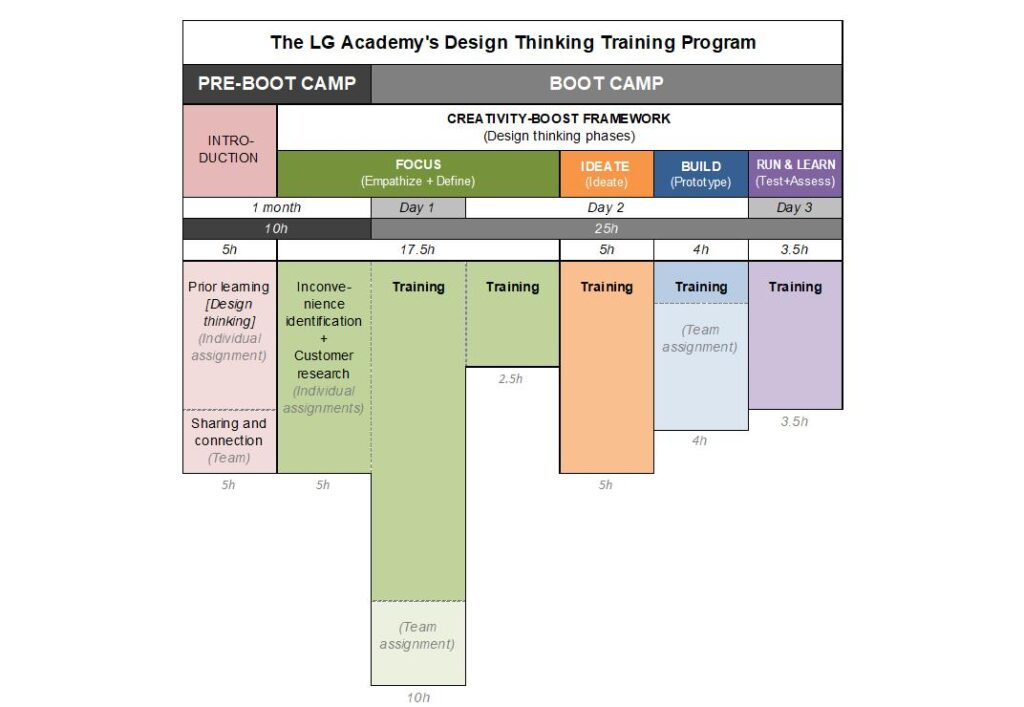

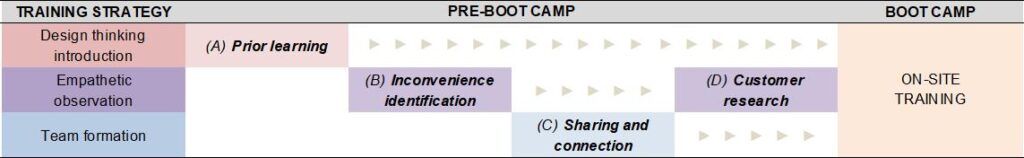

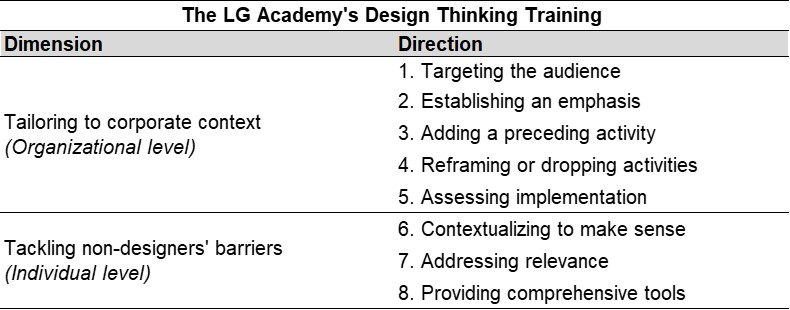

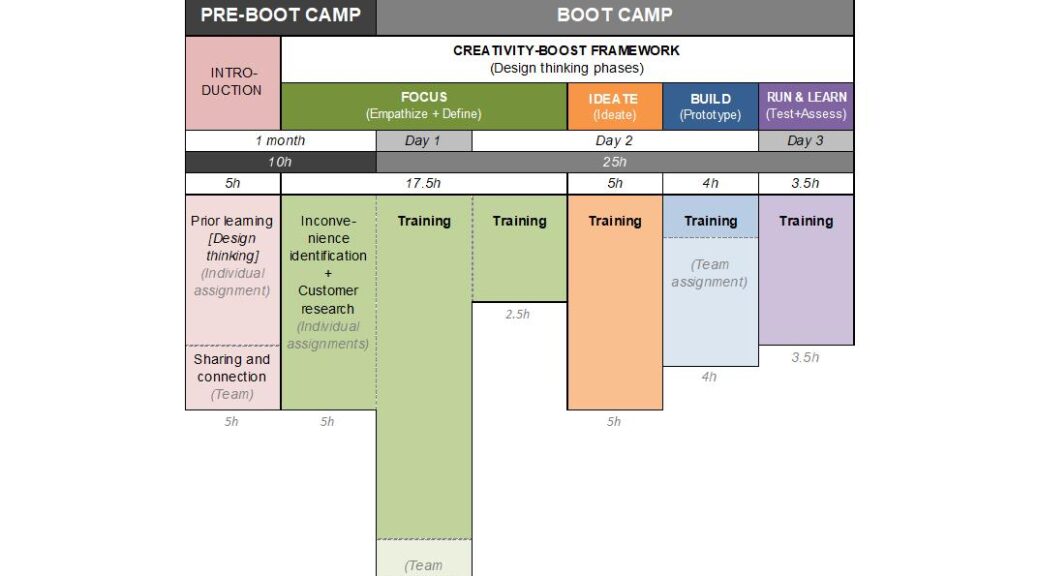

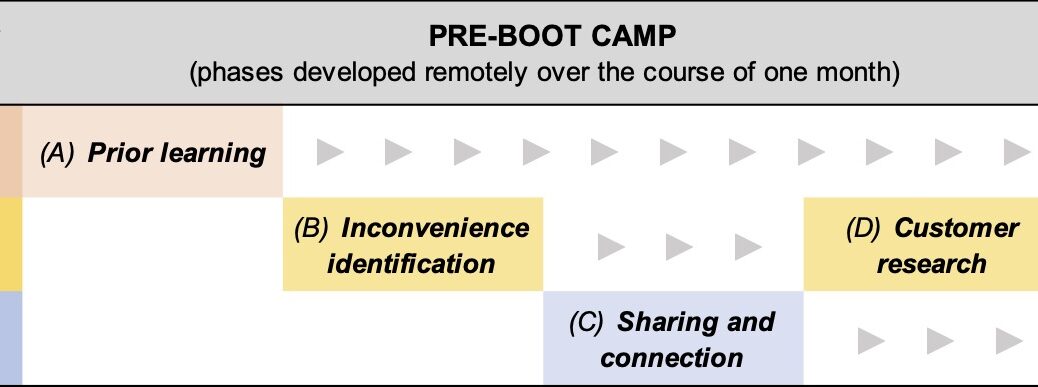

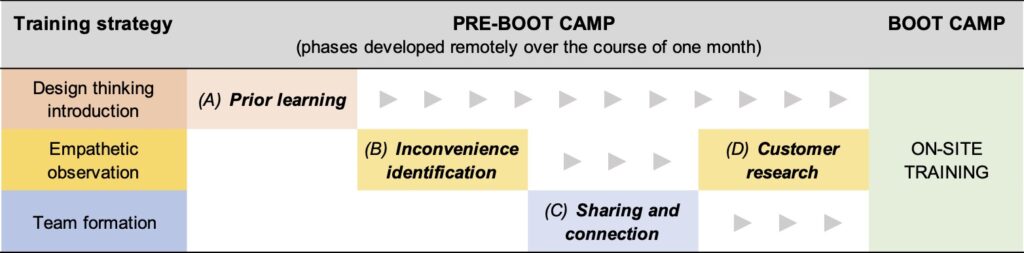

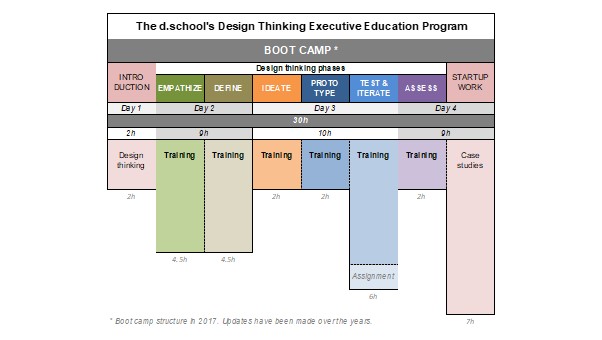

Organizations have sought to adopt design thinking aiming at innovation. However, implementing such a creative problem-solving approach based on designers’ mindsets and practices requires the navigation of obstacles. Corporate structure and culture hinder the adoption course, and cognitive barriers affect non-designer engagement. In this regard, training has been used as a means of easing the process. Although considered a crucial step in design thinking implementation, research on training initiatives is scarce in the literature. Most studies mirror that about d.school boot camp and innovative programs developed by companies globally remain unknown. This practice-oriented paper investigates a training blueprint tailored for LG Corporation in South Korea, targeting R & D personnel working in several affiliates that needed creative problem-solving skills to improve business performance. The study findings unveil a customized initiative that expanded the established boot camp model by adding preceding activities to increase learning opportunities and enable empathetic observation. Fundamentally, the customization strategy aimed to provide participants with customer-oriented tools to solve business problems. In addition, the training program reframed the design thinking steps in order to make it relevant for employees and foster corporate implementation goals. Ultimately, this case study supplies literature describing a training blueprint to disseminate design thinking considering two dimensions: individual adoption and organizational implementation challenges.

Keywords

design thinking, creative problem-solving, boot camp, training, customer orientation