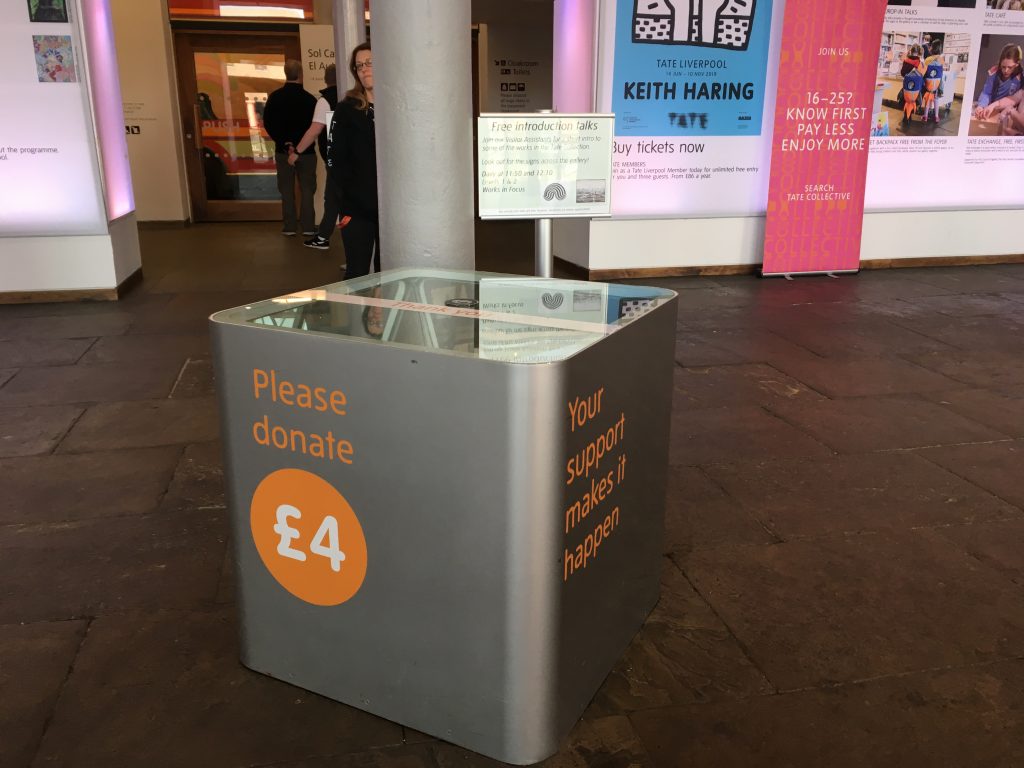

Starbucks Coffee Korea recently launched a set of limited edition Playmobil toy figures. Customers get one of six tall-size beverages with an accompanying Playmobil figure for $12.

Today at a nearby Starbucks, I found several customers paid extra to have a barista figure. Another Starbucks was crowded even though customers have to leave store shortly due to social distancing regulations. It suggests this campaign increases offline store traffic.

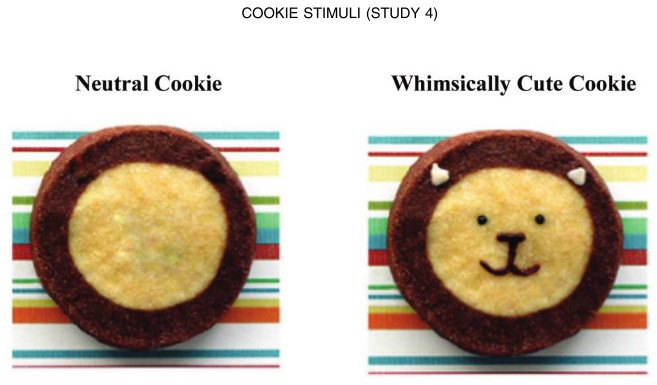

Why do adults like Starbucks toys? Although brand power and scarcity play key roles, a more deeply rooted reason is that Playmobil figures are whimsically cute. “Cute products (e.g., an ice-cream scoop shaped like a miniature person or a dress with tropical colors and pink flamingos) can have whimsical nature, which is associated with capricious humor and playful disposition. Whimsical cuteness is … associated with fun and playfulness.” (Nenkov and Scott 2014, pg. 327).

Interestingly, whimsically cute products do not necessarily appeal when they are designed for kids. Contrary to our belief, whimsical cuteness attracts adults. This argument is supported by the experimental findings obtained from a marketing paper.

***

Reference

Nenkov, G., & Scott, M. (2014). “So Cute I Could Eat It Up”: Priming Effects of Cute Products on Indulgent Consumption. Journal of Consumer Research,41(2), 326-341.

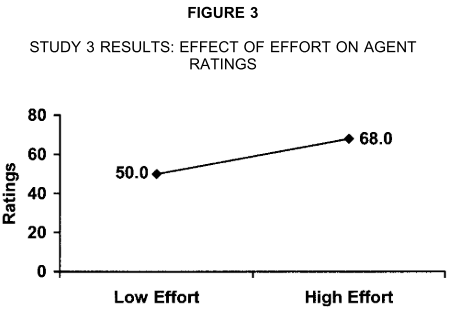

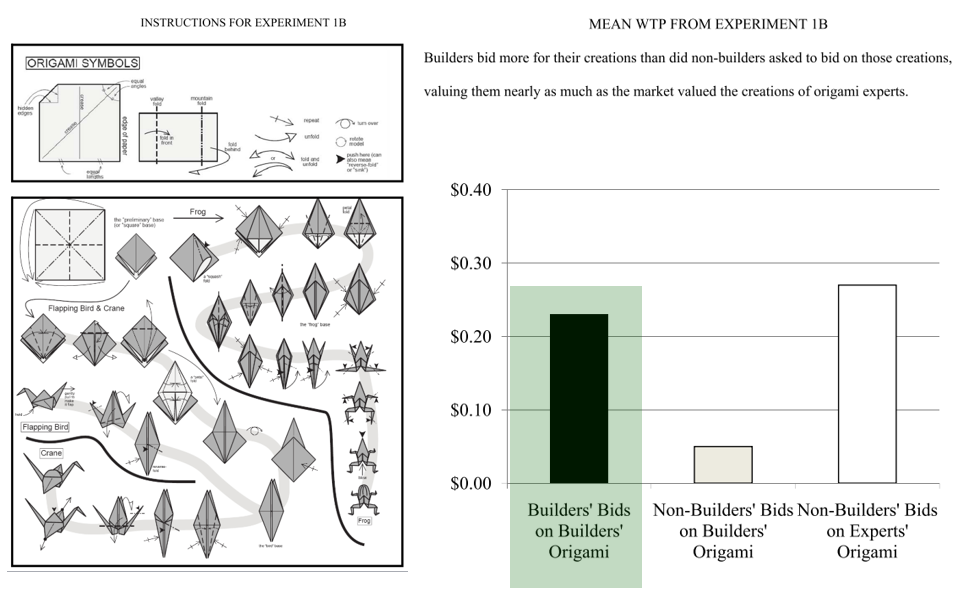

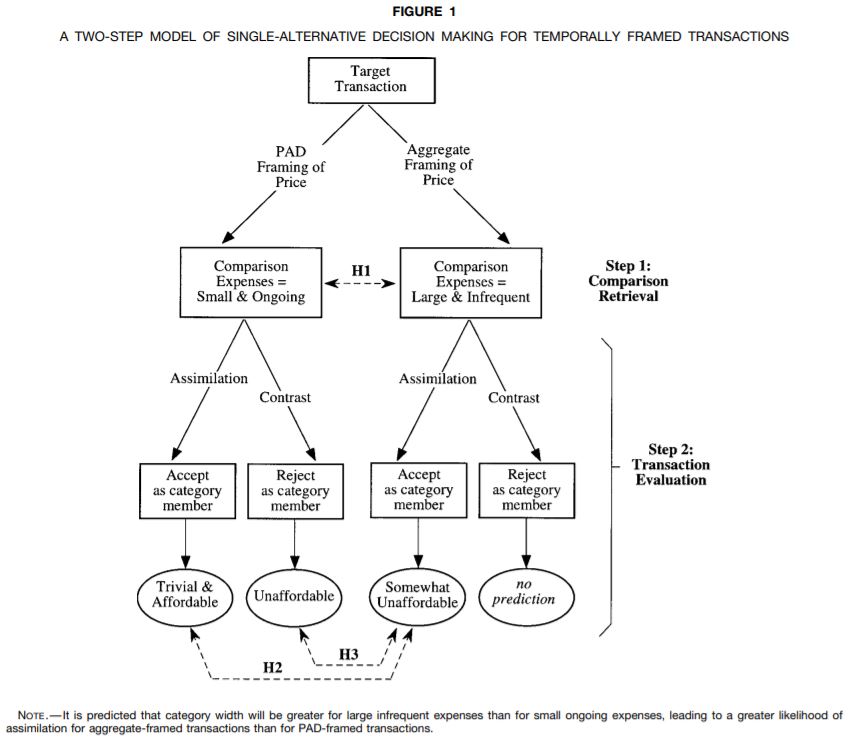

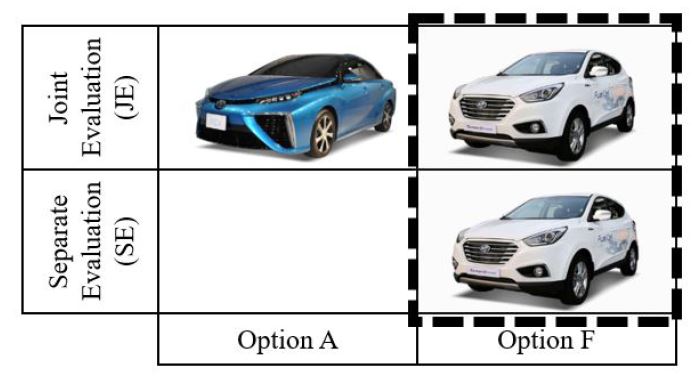

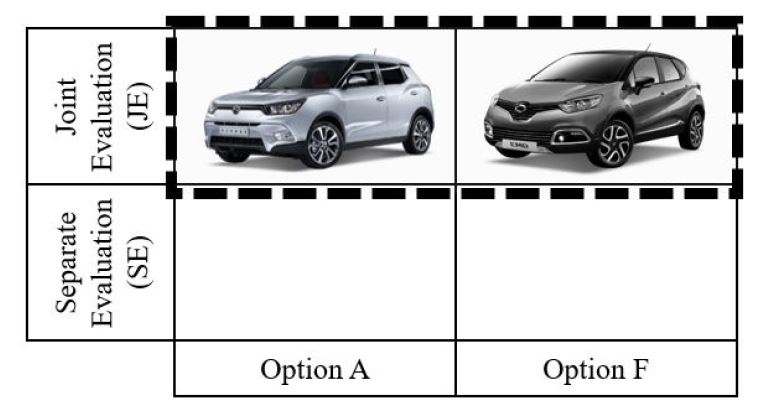

This article examines the extent to which consumers engage in more indulgent consumption when they are exposed to whimsically cute products and explores the process by which such products affect indulgence. Prior research on kindchenschema (baby schema) has found that exposure to cute babies or baby animals leads to more careful behavior (see the study by Sherman, Haidt, and Coan), suggesting restraint. The present research uncovers the opposite: consumers become more indulgent in their behavior after exposure to whimsically cute products. Drawing from research on cognitive priming, kindchenschema, anthropomorphization, indulgence, and regulatory focus, this research posits that exposure to whimsically cute products primes mental representations of fun, increasing consumers’ focus on approaching self-rewards and making consumers more likely to choose indulgent options. These effects do not emerge for kindchenschema cute stimuli, since they prime mental representations of vulnerability and caretaking. Four empirical studies provide evidence for the proposed effects and their underlying process.

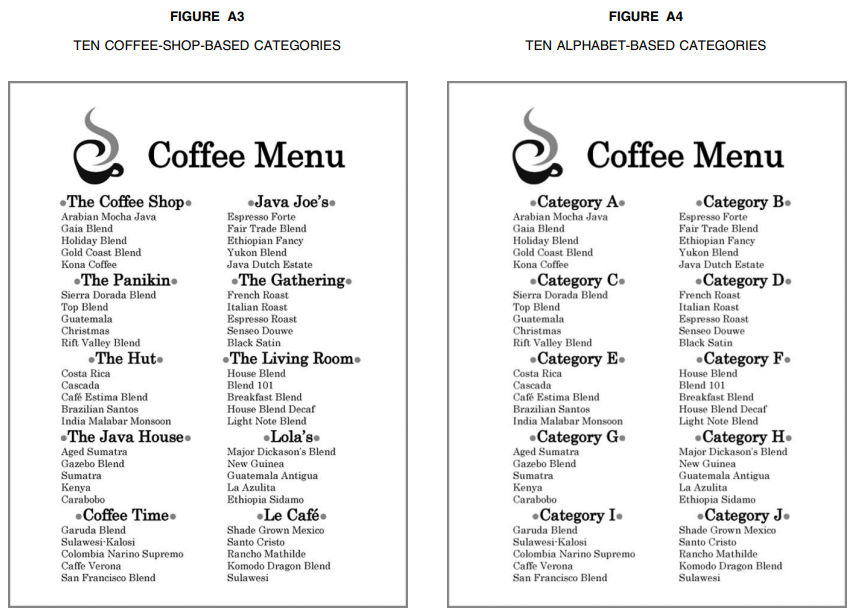

When two cookies were presented under “The Cookie Shop,” participants indicated significantly weaker preference for the healthy entree when they had earlier viewed the whimsically cute cookie than when they had viewed the neutral cookie. However, no such differences occurred when two cookies were presented under “The Kid’s Cookie Shop.”