I was recently invited by Shelley Takahashi, Professor of Industrial Design at California State University Long Beach, to speak to junior students about sustainability.

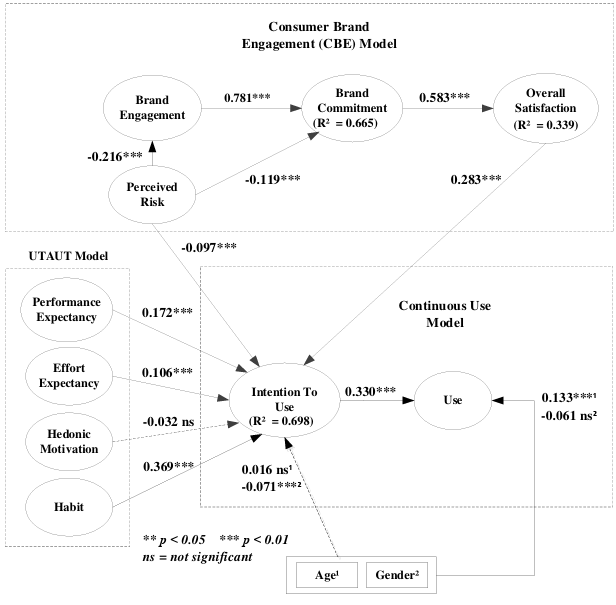

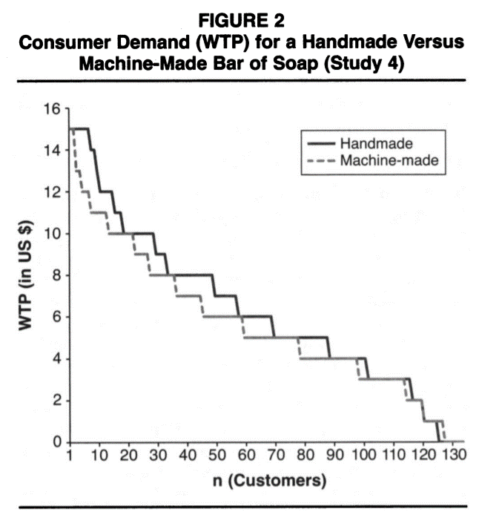

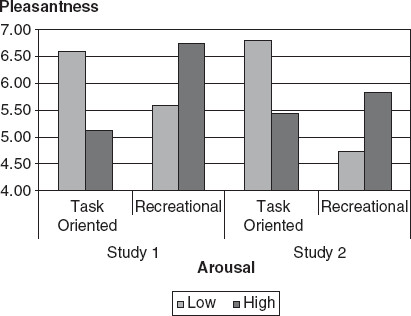

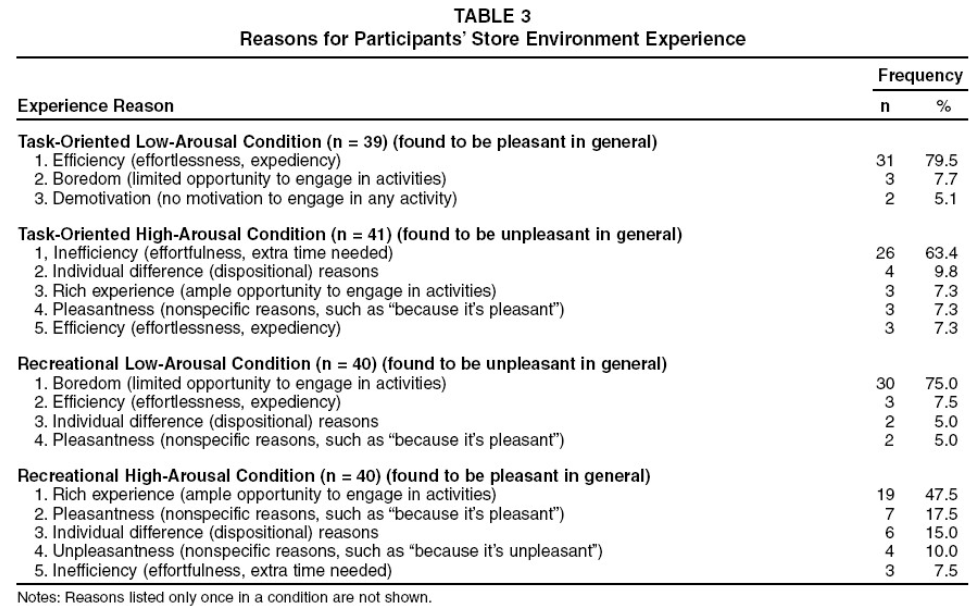

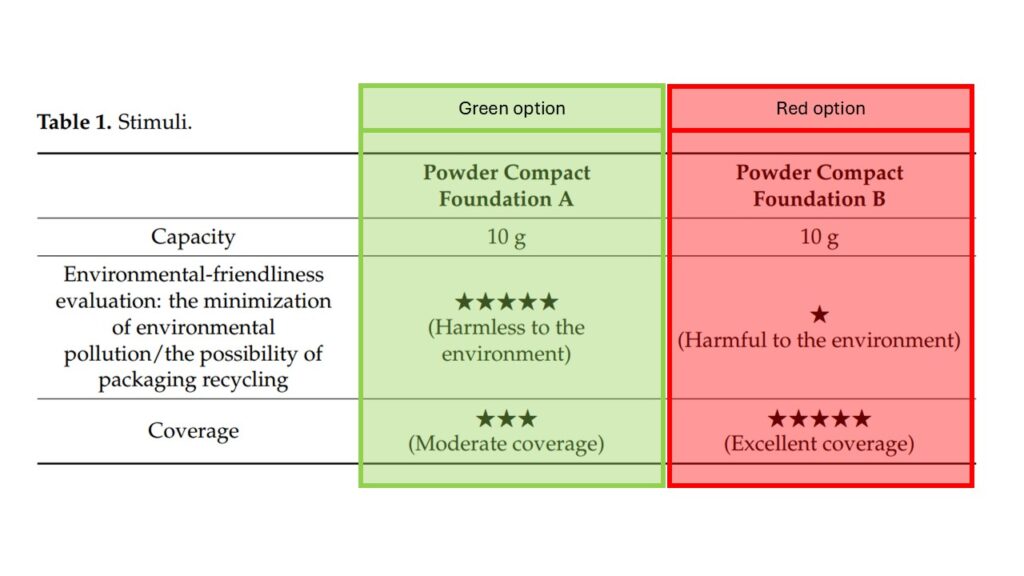

During this opportunity, I shared my research on green consumption conducted with Bohee Jung (Jung & Joo, 2021). We borrowed the concept of choice–preference inconsistency from consumer behavior research to test whether consumers over-choose green options even when they do not evaluate them highly.

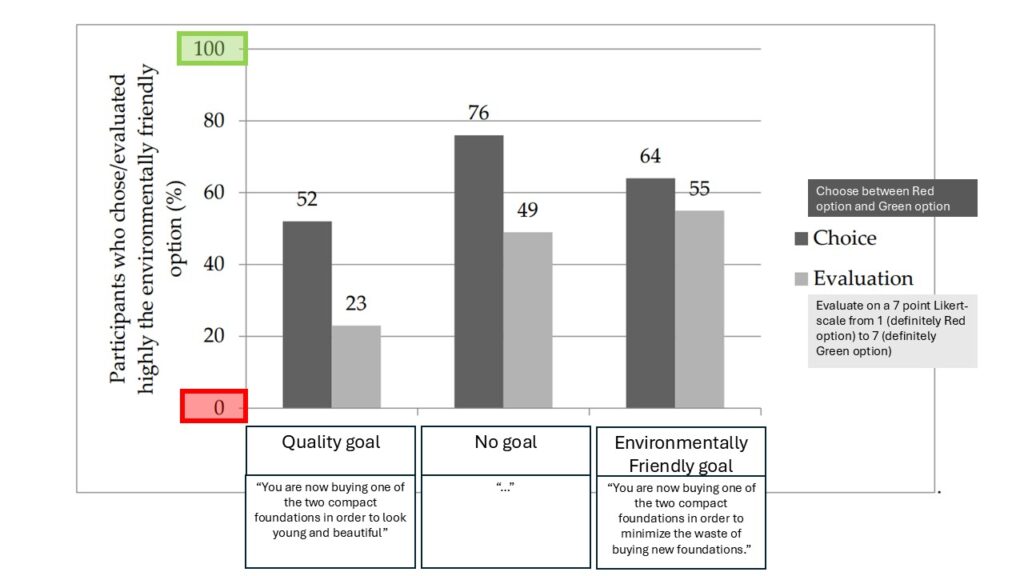

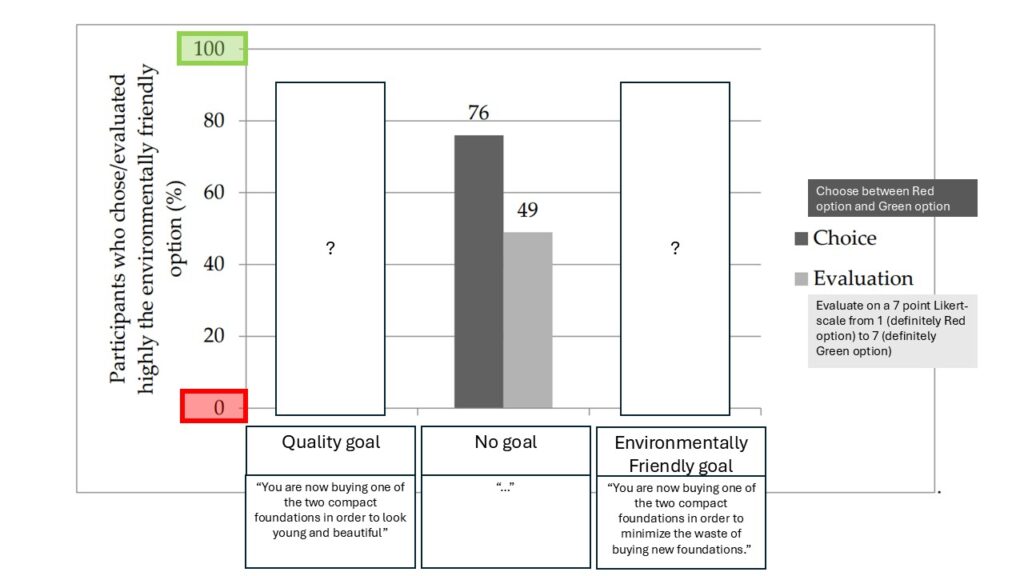

We found that while 76% chose the green option, only 49% actually rated it more favorably. A similar gap can be seen in real-world cases like the hype around Starbucks plastic reusable cups. Although companies are often accused of greenwashing, consumers themselves contribute by over-choosing green products they do not fully use.

***

Reference

Jung, B., & Joo, J. (2021). Blind Obedience to Environmental Friendliness: The Goal Will Set Us Free. Sustainability, 13(21), 12322.

In the past, researchers focusing on environmentally friendly consumption have devoted attention to the intention–action gap, suggesting that consumers have positive attitudes toward an environmentally friendly product even though they are not willing to buy it. In the present study, we borrow insights from the behavioral decision making literature on preference reversal to introduce an opposite phenomenon—that is, consumers buying an environmentally friendly product even though they do not evaluate it highly. We further rely on the research on goals to hypothesize that choice–evaluation discrepancies disappear when consumers pursue an environmentally friendly goal. A two (Mode: Choice vs. Evaluation) by three (Goal: Control vs. Quality vs. Environmentally friendly) between-subjects experimental design was used to test the proposed hypotheses. Our findings obtained from 165 undergraduate students in Korea showed that, first, 76% of the participants chose an environmentally friendly cosmetic product whereas only 49% of the participants ranked it higher than a competing product, and, second, when participants read the sentence “You are now buying one of the two compact foundations in order to minimize the waste of buying new foundations,” the discrepancy disappeared (64% vs. 55%). Our experimental findings advance academic discussions of green consumption and the choice–evaluation discrepancy and have practical implications for eco-friendly marketing.