Yoon, N., Park, W., & Joo, J. (2022). Dark side of cuteness: Effect of whimsical cuteness on new product adoption. In G. Bruyns & H. Wei (Eds.), [ _ ] With Design: Reinventing Design Modes (pp. 617–633). Singapore: Springer.

Abstract

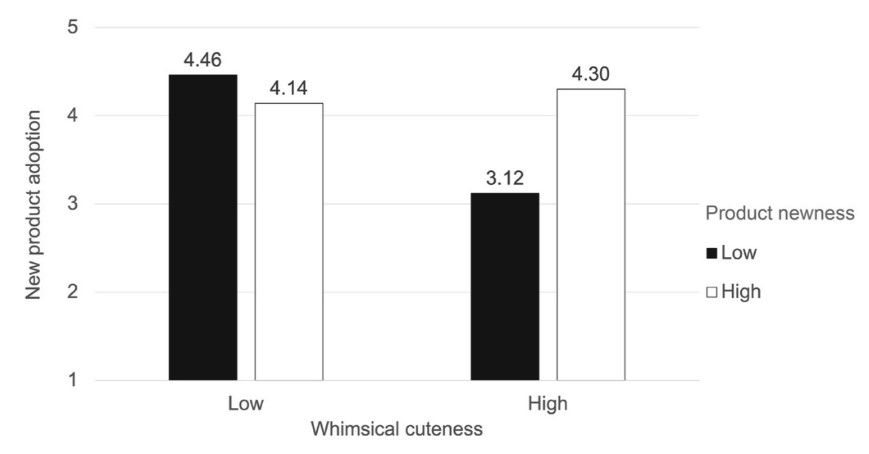

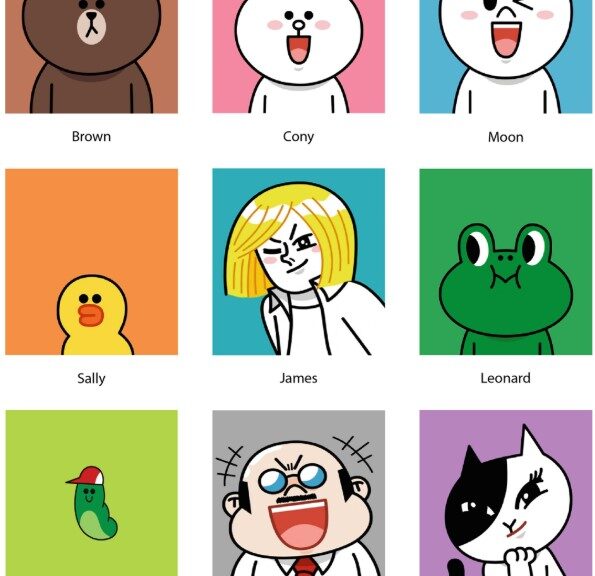

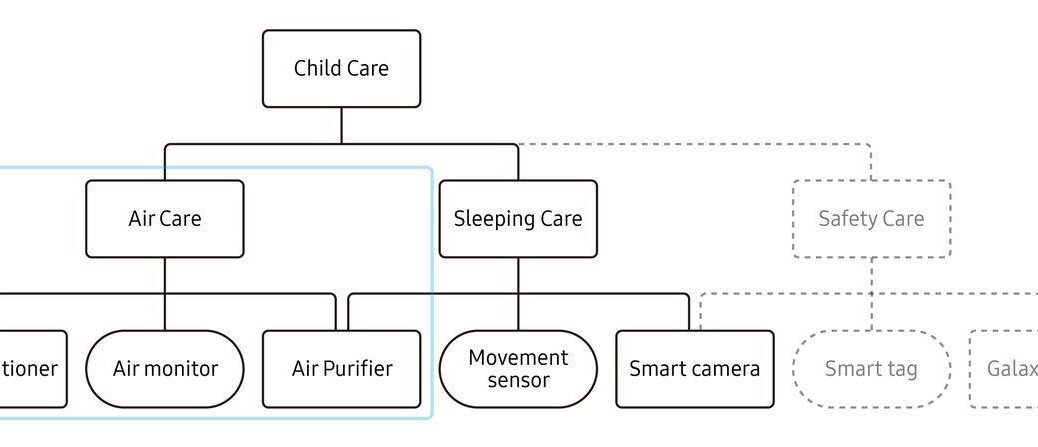

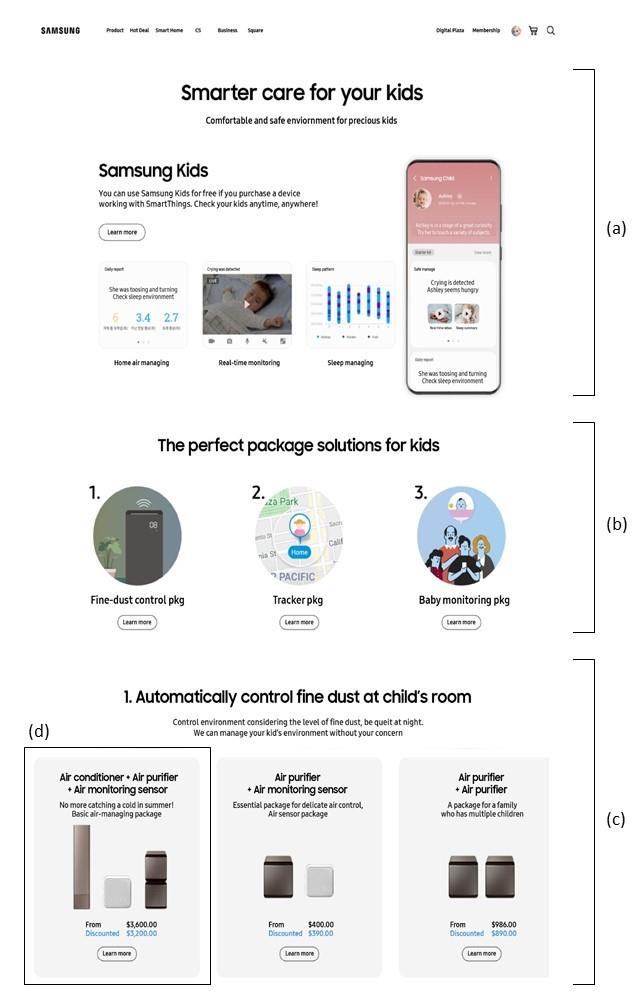

A wide range of businesses actively use cute characters such as the globally popular LINE FRIENDS characters for product design to increase consumers’ product adoption. Prior research has found that whimsical cuteness—which elicits fun and playful mental representations—can lead to higher product adoption. The effectiveness, however, has been investigated mostly in indulgent contexts. This article aims to uncover the opposite phenomenon, that is, whimsical cuteness could be detrimental for product adoption, in particular, in a non-indulgent context. In a pre-test, we measured the different types of cuteness of nine LINE FRIENDS characters, selecting one pair of characters differed only in terms of whimsical cuteness. Additionally considering product newness, the main study tested whether product adoption differed depending on the level of whimsical cuteness and product newness. The results demonstrate that participants were less likely to adopt a non-indulgent product when it was highly whimsically cute compared to less whimsically cute because the indulgence provoked by fun and playful mental representations conflicted against the restraint reinforced by a product for self-control. The adverse effect increases when the product has lower product newness whereas high product newness dampens the effect. The findings suggest that practitioners should carefully consider product nature and newness when applying whimsically cute features to product design and marketing promotions. This study has originality in that it is the first to demonstrate the adverse effect of whimsical cuteness on new product adoption and verify the moderating effect of product newness.

Keywords

Whimsical cuteness, New product adoption, Product newness, Self-control, LINE FRIENDS

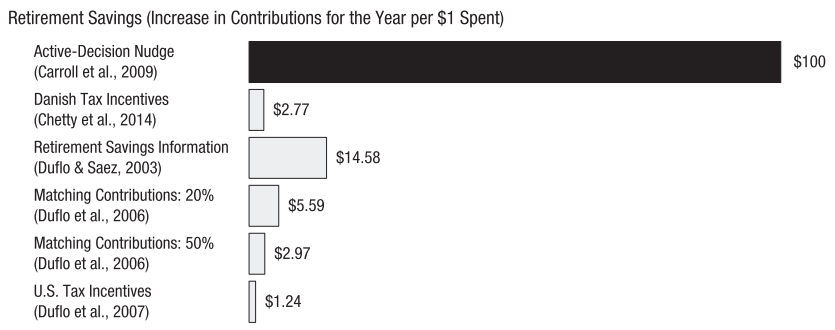

The key practical significance is that a product design which makes products seem whimsically cute has potentially detrimental effects on consumers’ product adoption, especially when the products are non-indulgent. Although nudge is an interesting lens for designers (Chen et al. 2019), our finding suggests that whimsical cuteness can have counter-nudging effects (Saghai 2013; Sunstein 2017) that make consumers not to adopt self-control products, contrary to the expectation of designers and marketers. For instance, cute characters with high whimsical cuteness might in fact hinder consumers’ adoption of products for self-control such as diet foods and time and study management products. Thus, practitioners should beware of using whimsically cute characters on products related to self-control (pg. 629).