The Institute of Design, Illinois Institute of Technology, and the Design & Emotion Society are pleased to invite you to participate in the 7th International Conference on Design & Emotion in Chicago. The International Conference on Design & Emotion is a forum held every other year where practitioners, researchers and industry leaders meet and exchange knowledge and insights concerning the cross-disciplinary field of design and emotion. The conference will offer workshops, research paper presentations, design case presentations, and poster presentations.

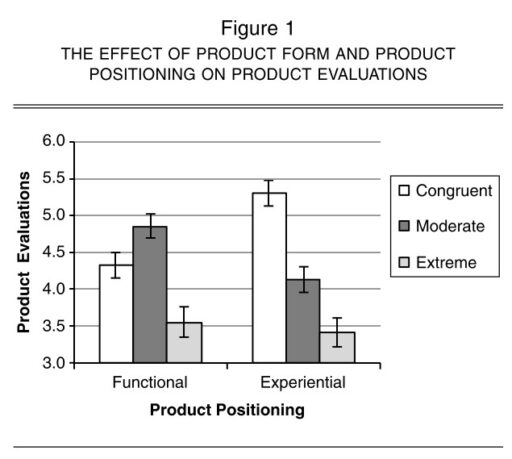

This conference covers various issues including Design for Environments, Service Design, Strategic Design and Business, and Foundation for Design and Emotion. I presented my work on context-dependent design evaluations.

I was pleased to have conversations with many creative designers as well as insightful design researchers. In particular, four presentation excited me. Two of them discuss new product development and the other two discuss product design.

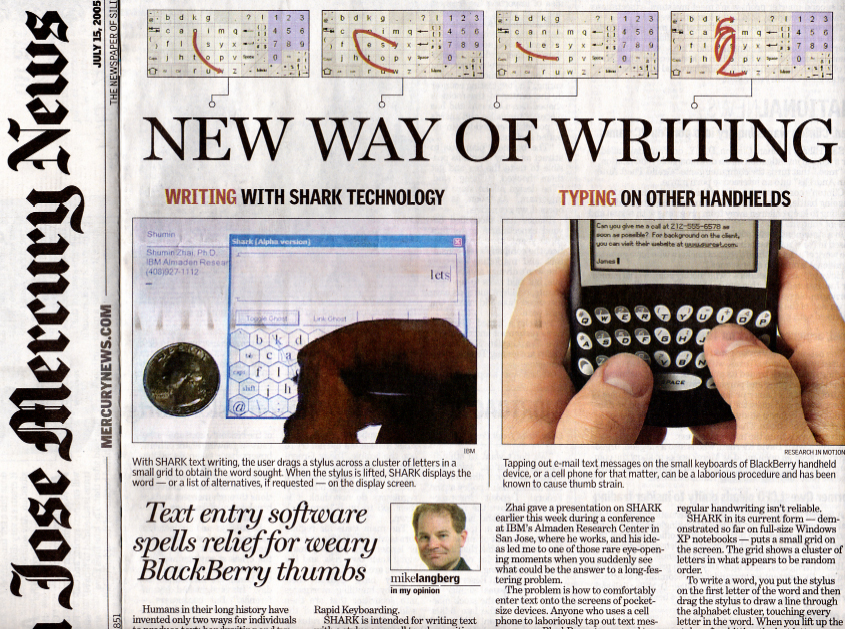

1. “Improvisational Comedy and Product Design Ideation: Making Non-Obvious Connections between Seemingly Unrelated Thing”

Barry Kudrowitz and David Wallace from MIT try to identify those who are good at developing new products. Inspired by the procedural similarity between making a comedy and developing a new product, they propose that comedians are good new product developers. Then, they support their hypothesis by demonstrating that the quantity and the quality of cartoon captions made by comedians are greater and better than those made by non-comedians.

2. “User Research Methods: Distinctive Need Expressions from an In-depth Interview and a Generative Method Market Research”

Hyesun Hwang and Ki-Ok Kim from Sungkyunkwan University compare two user research methods, in-depth interviews and generative methods (prototyping). They argue that the two methods collect different consumer needs. An empirical study suggests that the in-depth interview produces concrete, negative and past-oriented problems, whereas the generative method produces abstract, positive and future-oriented ideas.

3. “The Cute Look: Baby-Schema Effects in Product Design”

Linda Miesler from University of St. Gallen investigates whether face-like features of the car fronts (head lights and air intake) are processed analog to human faces (eyes and mouth). She demonstrates in an experiment that enlarging the headlights (“larger eyes”) and increasing the size of the air intake (“thicker lips”) led people to perceive the car fronts cuter.

4. “The Relationship between Eco Design and Emotional Experiences”

Heesook Jung from Seoul National University proposes that ecofriendly behavior requires effort and, therefore, some motivation such as playfulness should be employed to help consumers behave ecofriendly. She presents a case of Lohas, an ecofriendly Japanese bottled water. According to her, the sound that an empty bottle creates when squeezed leads consumers to behave more ecofriendly (e.g., squeezing bottles) (see Lohas commercial).