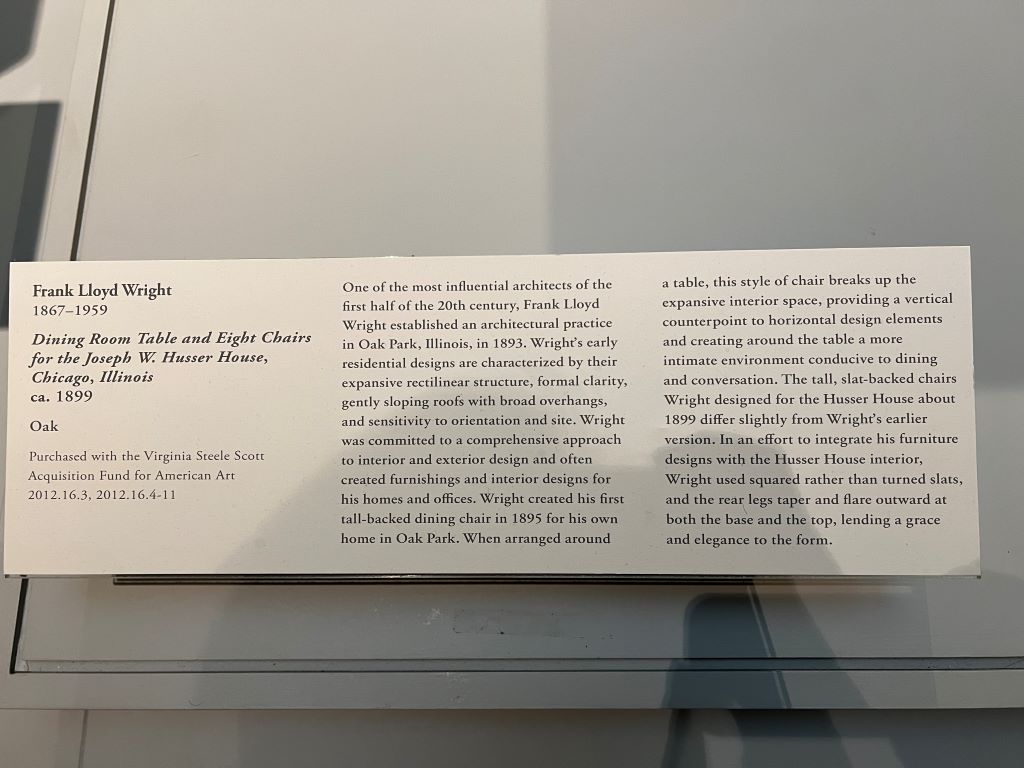

At the Huntington Art Museum in Los Angeles, I was captivated by a dining room table and chairs. They were not vibrant but organized. They were meticulously crafted. I could not take my eyes off these sophisticated colorful items.

Nearby, a reclining chair caught my attention as well. When I looked closer, I discovered these pieces were designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Suddenly, everything made sense to me. His furniture mirrored his architecture—minimalistic, harmonious, and timeless. His work, including the famous Fallingwater, follows these principles.

This experience reminded me of how knowing the creator enhances our appreciation of a product. When we learn who made it, we love it more. This idea was supported by a research about wine, showing that a wine named after the winery founder’s grandfather boosts consumer confidence. Even Apple, under Tim Cook, continues to build on this principle. We are deeply connected to the stories behind the objects.

***

Reference (Fallingwater at Wikipedia)

Fallingwater is, according to Wikipedia, a house designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1935. Situated in the Mill Run section of Stewart township, in the Laurel Highlands of southwest Pennsylvania, about 70 miles (110 km) southeast of Pittsburgh in the United States, it is built partly over a waterfall on the Bear Run river. The house was designed to serve as a weekend retreat for Liliane and Edgar J. Kaufmann, the owner of Pittsburgh’s Kaufmann’s Department Store.

After its completion, Time called Fallingwater Wright’s “most beautiful job” and it is listed among Smithsonian’s “Life List of 28 Places to See Before You Die”. The house was designated a National Historic Landmark on May 11, 1976. In 1991, members of the American Institute of Architects named Fallingwater the “best all-time work of American architecture” and, in 2007, ranked Fallingwater 29th on its “America’s Favorite Architecture” list.

Eight of Frank Lloyd Wright’s buildings – Fallingwater, the Guggenheim Museum, the Hollyhock House, the Jacobs House, the Robie House, Taliesin, Taliesin West, and the Unity Temple – were inscribed on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites under the title The 20th-century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright in July 2019. UNESCO stated that these buildings were “innovative solutions to the needs for housing, worship, work or leisure” and “had a strong impact on the development of modern architecture in Europe.”