Boudin Bakery at Fisherman’s Wharf is well known for its sourdough bread. Many visitors stop by to enjoy clam chowder served in a sourdough bowl.

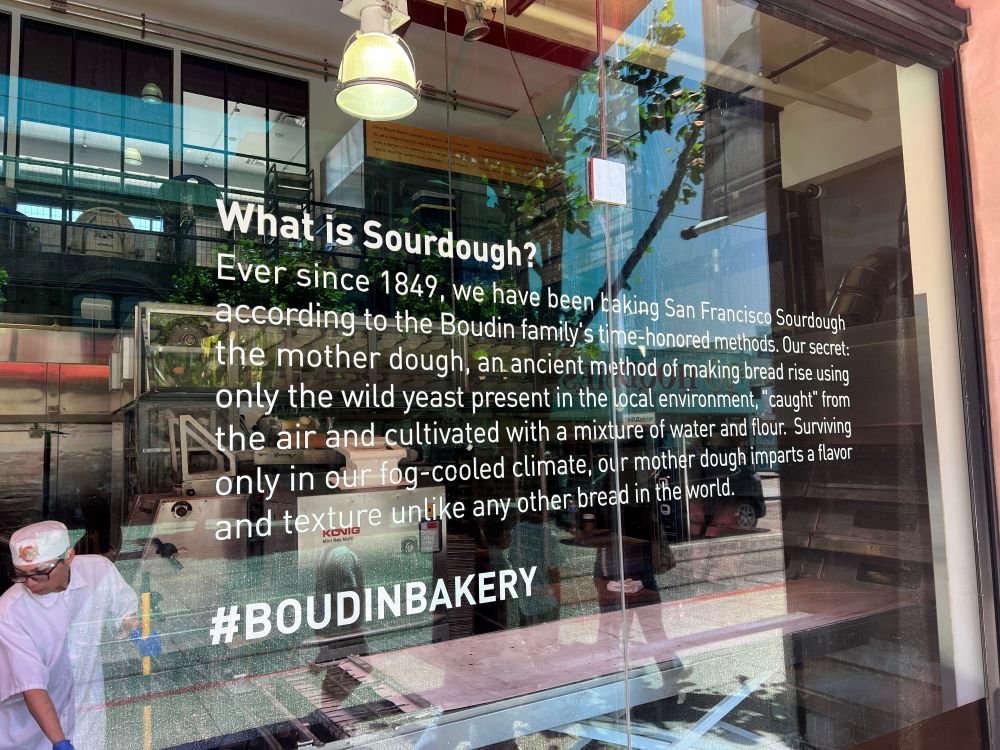

What is Sourdough?

Ever since 1849, we have been baking San Francisco Sourdough according to the Boudin family’s time-honored methods. Our secret: the mother dough, an ancient method of making bread rise using only the wild yeast present in the local environment, “caught” from the air and cultivated with a mixture of water and flour. Surviving only in our fog-cooled climate, our mother dough imparts a flavor and texture unlike any other bread in the world.

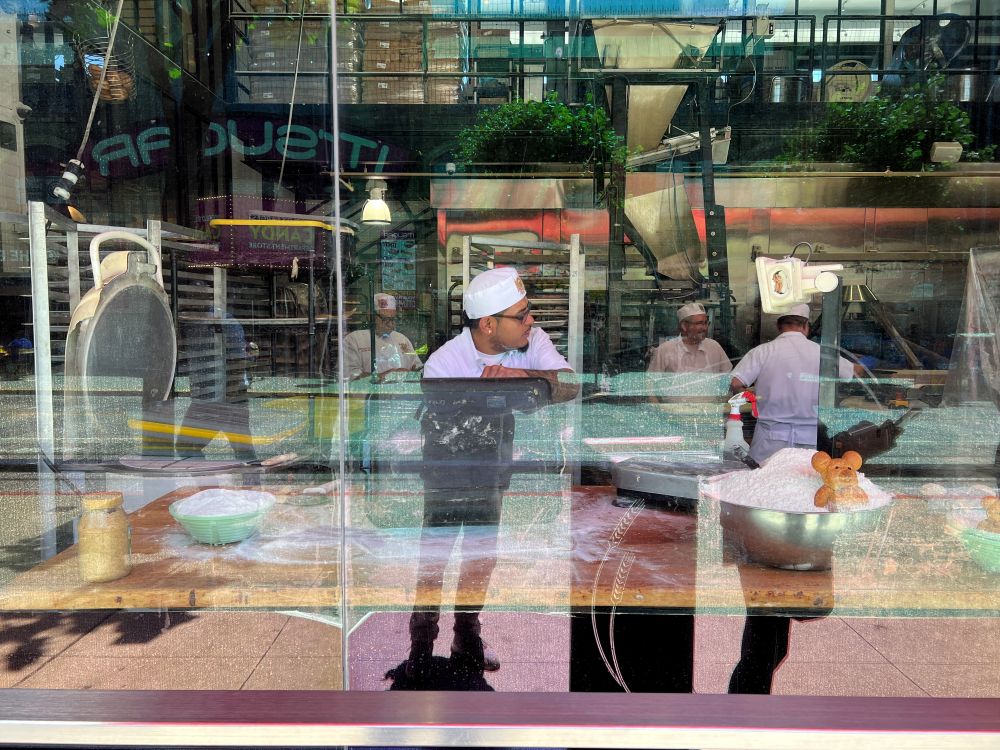

When I visited, I noticed many people were watching how the bread was made.

Inside the building, several bakers were mixing flour, shaping dough, and baking loaves behind large glass windows. Many people stood outside, quietly observing. They were interested in the process, not just the final food. I was curious about why people care about how something is made.

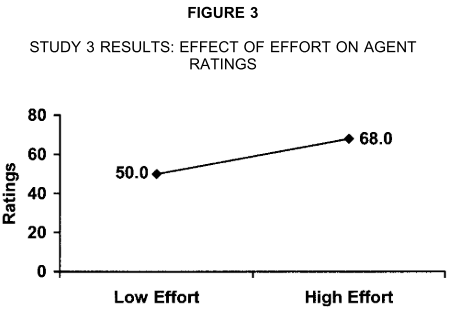

Usually, marketers focus on product benefits. However, consumers may pay greater attention to how a product is made. There could be two reasons. First, they may want to avoid harmful ingredients and look for safety. Second, they may want to give credit to those who work hard.

Regardless of the reasons, marketers should not focus only on product outcomes. They should also make the production process more visible and highlight the makers’ effort. Showing what happens behind the scenes can have a strong impact on how people see the product.

***

Reference 1

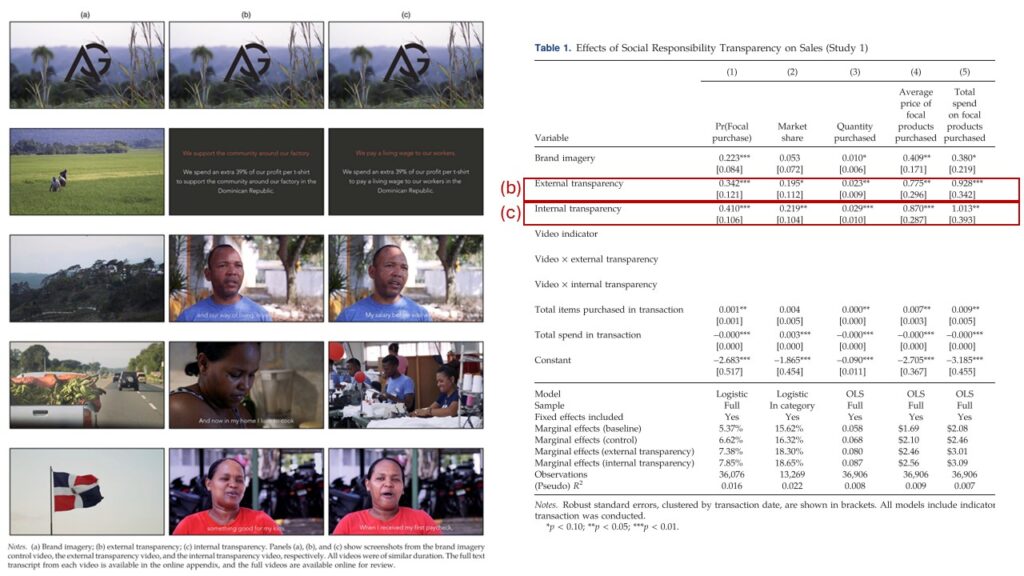

Buell, R. W., & Kalkanci, B. (2021). How transparency into internal and external responsibility initiatives influences consumer choice. Management Science, 67(2), 932–950.

Amid growing calls for transparency and social and environmental responsibility, companies are employing different strategies to improve consumer perceptions of their brands. Some pursue internal initiatives that reduce their negative social or environmental impacts through responsible operations practices (such as paying a living wage to workers or engaging in environmentally sustainable manufacturing). Others pursue external responsibility initiatives (such as philanthropy or cause-related marketing). Through two experiments conducted in the field and complementary online experiments, we compare how transparency into these internal and external initiatives affects customer perceptions and sales. We find that transparency into both internal and external responsibility initiatives tends to dominate generic brand marketing in motivating consumer purchases, supporting the view that consumers take companies’ responsibility efforts into account in their decision making. Furthermore, the results provide converging evidence that transparency into a company’s internal responsibility practices can be at least as motivating of consumer sales as transparency into its external responsibility initiatives, incrementally increasing a consumer’s probability of purchase by 6.40% and 45.85% across our two field experiments, conducted in social and environmental domains, respectively. Our results suggest that it may be in the interest of both business and society for managers to prioritize internal responsible operations initiatives to achieve both top- and bottom-line benefits while mitigating social and environmental harms.

***

Reference 2

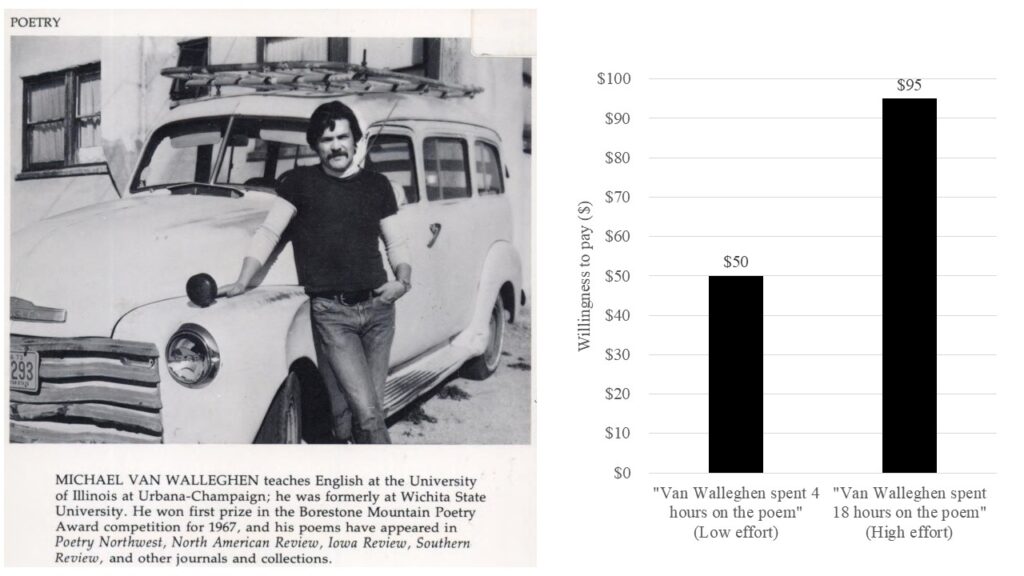

Kruger, J., Wirtz, D., Van Boven, L., & Altermatt, T. W. (2004). The effort heuristic. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(1), 91–98.

The research presented here suggests that effort is used as a heuristic for quality. Participants rating a poem (Experiment 1), a painting (Experiment 2), or a suit of armor (Experiment 3) provided higher ratings of quality, value, and liking for the work the more time and effort they thought it took to produce. Experiment 3 showed that the use of the effort heuristic, as with all heuristics, is moderated by ambiguity: Participants were more influenced by effort when the quality of the object being evaluated was difficult to ascertain. Discussion centers on the implications of the effort heuristic for everyday judgment and decision-making.

***

Reference 3

Morales, A. C. (2005). Giving firms an “E” for effort: Consumer responses to high-effort firms. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 806–812.

This research shows that consumers reward firms for extra effort. More specifically, a series of three laboratory experiments shows that when firms exert extra effort in making or displaying their products, consumers reward them by increasing their willingness to pay, store choice, and overall evaluations, even if the actual quality of the products is not improved. This rewarding process is defined broadly as general reciprocity. Consistent with attribution theory, the rewarding of generally directed effort is mediated by feelings of gratitude. When consumers infer that effort is motivated by persuasion, however, they no longer feel gratitude and do not reward high-effort firms.

***

Reference 4

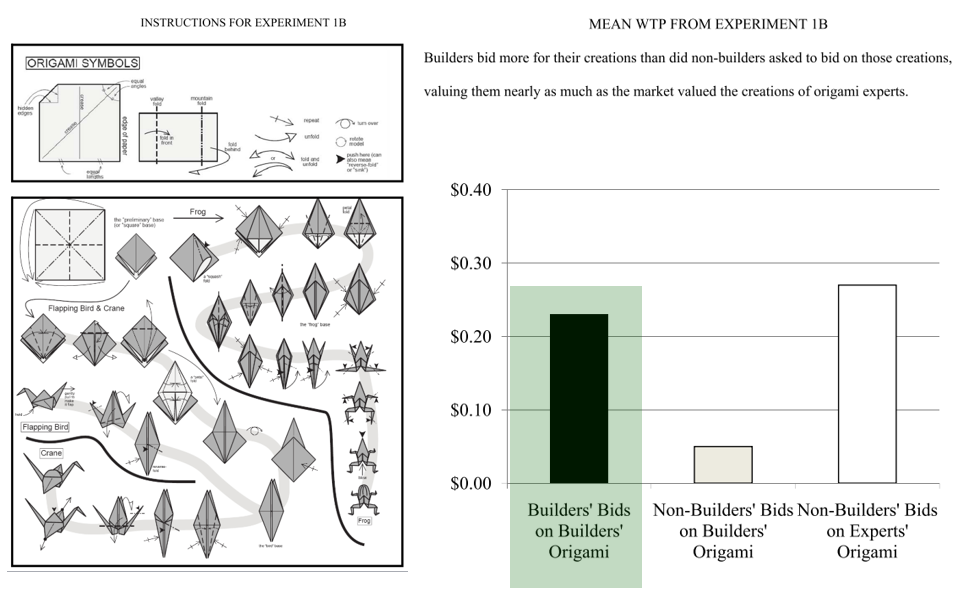

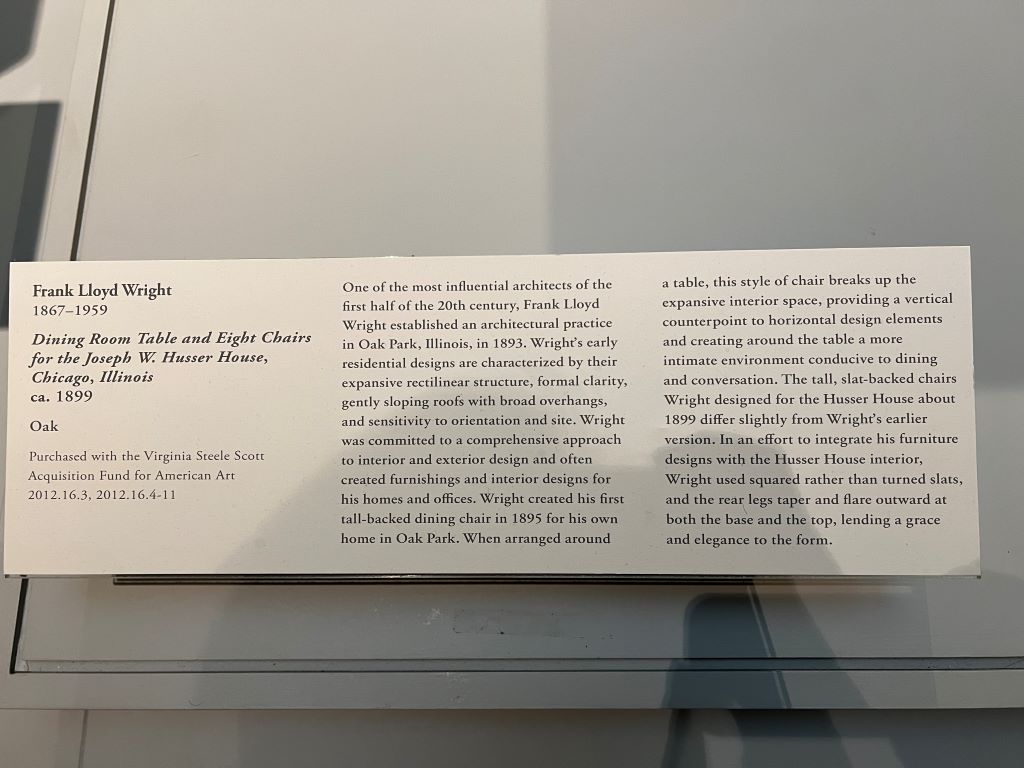

Norton, M. I., Mochon, D., & Ariely, D. (2012). The “IKEA Effect”: When labor leads to love. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(3), 453–460.

In four studies in which consumers assembled IKEA boxes, folded origami, and built sets of Legos, we demonstrate and investigate boundary conditions for the IKEA effect-the increase in valuation of self-made products. Participants saw their amateurish creations as similar in value to experts’ creations, and expected others to share their opinions. We show that labor leads to love only when labor results in successful completion of tasks; when participants built and then destroyed their creations, or failed to complete them, the IKEA effect dissipated. Finally, we show that labor increases valuation for both “do-it-yourselfers” and novices.