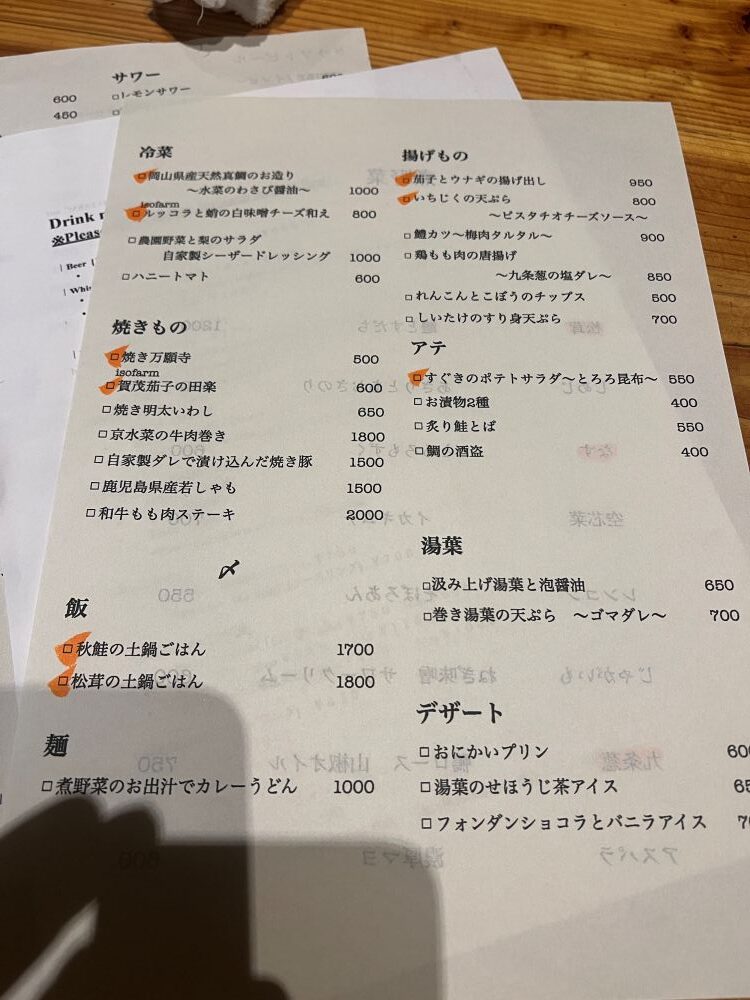

I recently visited D&Department Kyoto (ディアンドデパートメントプロジェクト), a store in Japan dedicated to enduring value. D&Department champions “Long Life Design,” promoting sturdy, regional, and sometimes used products.

One marketing lesson comes from the store’s special location inside Bukkō-ji Temple. When I walked from the temple’s old courtyard into the shop, every object instantly looked more valuable.

A simple cup, which might look just functional online, becomes a curated object filled with the temple’s sense of history. The environment transforms the act of shopping into a cultural thing. Even used items are valuable pieces of good design.

I think the physical store works as a contextual amplifier. It makes the perceived value of every item higher. The products work together, and their collective value is bigger than their individual parts. I saw the same phenomena at the Jeju café (http://designmarketinglab.com/archives/6550) and also at the Napa Valley winery (http://designmarketinglab.com/archives/7444).

Studies confirm the physical store is necessary for physical engagement with “deep products” like used items. The quality of the physical retail environment is a direct antecedent to the customer’s overall value creation and experience. This is particularly true for high-design goods that require multi-sensory inspection for customers to feel confident in their purchase.

***

Reference

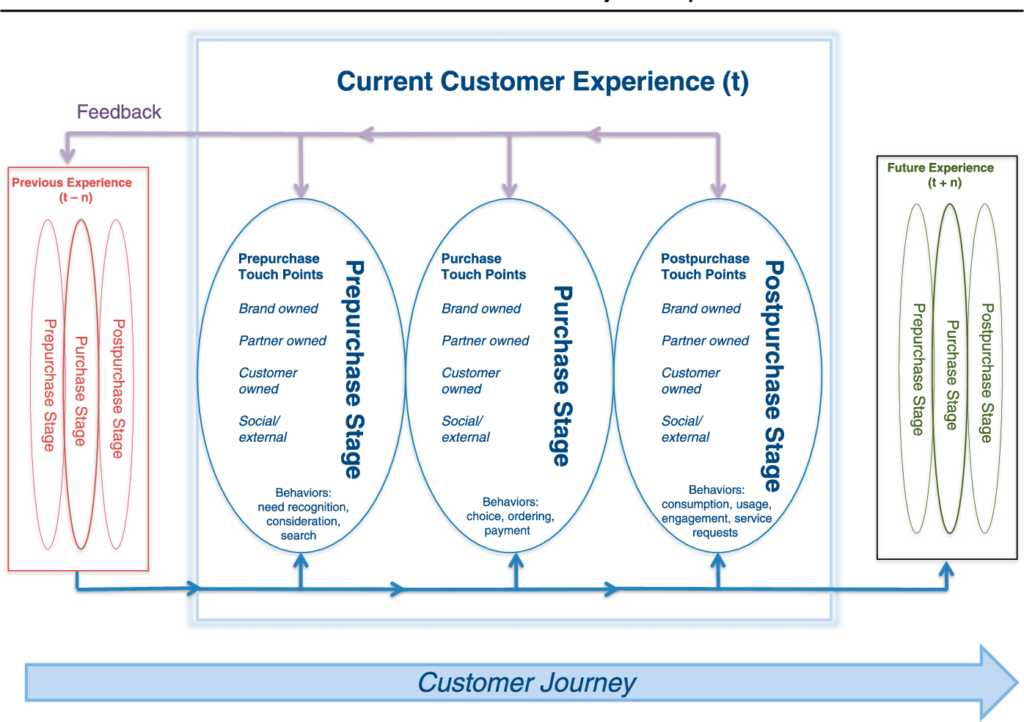

Verhoef, P. C., Lemon, K. N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2009). Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of retailing, 85(1), 31-41.

Retailers, such as Starbucks and Victoria’s Secret, aim to provide customers a great experience across channels. In this paper we provide an overview of the existing literature on customer experience and expand on it to examine the creation of a customer experience from a holistic perspective. We propose a conceptual model, in which we discuss the determinants of customer experience. We explicitly take a dynamic view, in which we argue that prior customer experiences will influence future customer experiences. We discuss the importance of the social environment, self-service technologies and the store brand. Customer experience management is also approached from a strategic perspective by focusing on issues such as how and to what extent an experience-based business can create growth. In each of these areas, we identify and discuss important issues worthy of further research.