California is not bike-friendly and I decided to look for a used car. I found a car I liked on CarGurus.com and scheduled a test drive it. But just a day before my visit, I received a text saying the car had already been sold. It was frustrating.

Therefore, I decided to visit CarMax, the used car dealership many people recommend. I was not expecting much, but to my surprise, the experience turned out to be refreshing.

The first thing I noticed was clean, bright, and organized. It felt like an IKEA store. In particular, the lighting gave the whole place a welcoming vibe. It made me feel freshly excited, which is not something I associate with used car shopping.

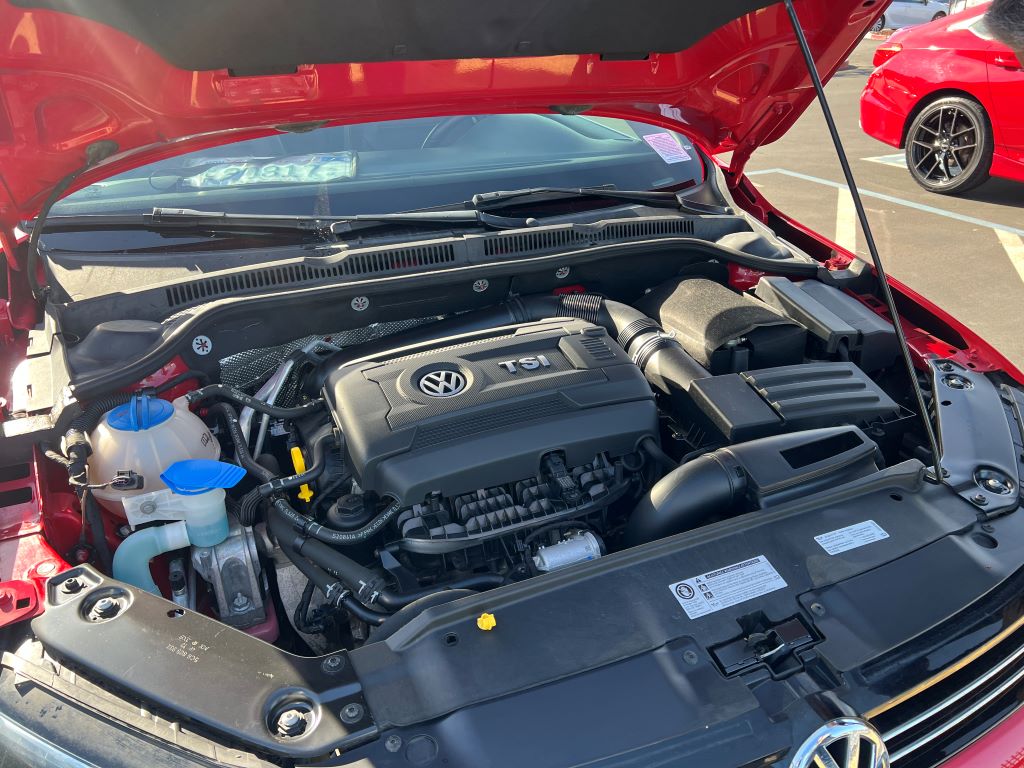

Secondly, the way salesperson worked with me was unexpected. At Bank of America, the teller kept the screen to themselves while I sat behind it. At Carmax, however, the salesperson shared his screen with me. He and I went through the car’s history, the price breakdown, and all the details together. It felt like we were on the same team, not buyer and seller. Interestingly, he was not knowledgeable about cars, but that helped me feel less intimidating and more relaxed. Sharing the screen was a simple but powerful gesture.

Finally, the cars and the prices were the same as advertised. When I arrived at the parking lot, the cars I came to test drive were there, just as promised, with no need for negotiation. It reminded me of WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get).

CarMax might be slightly pricier than other dealerships, but I am willing to pay a premium for the peace of mind it brings. The bright store design, transparent sales process, and WYSIWYG style inventory transformed a frustrating car buying experience into something positive.

***

Reference (bright store design for visitor experience)

Spence, C., Puccinelli, N. M., Grewal, D., & Roggeveen, A. L. (2014). Store atmospherics: A multisensory perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 31(7), 472–488.

Store atmospherics affect consumer behavior. This message has created a revolution in sensory marketing techniques, such that across virtually every product category, retailers and manufacturers seek to influence the consumer’s “sensory experience.” The key question is how should a company design its multisensory atmospherics in store to ensure that the return on its investment is worthwhile? This paper reviews the scientific evidence related to visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory aspects of the store environment and their influence on the consumer’s shopping behavior. The findings emphasize the need for further research to address how the multisensory retail environment shapes customer experience and shopping behavior.

***

Reference (transparent sales process for user experience)

Roten, Y. S., & Vanheems, R. (2023). To share or not to share screens with customers? Lessons from learning theories. Journal of Services Marketing, 37(1), 65–77.

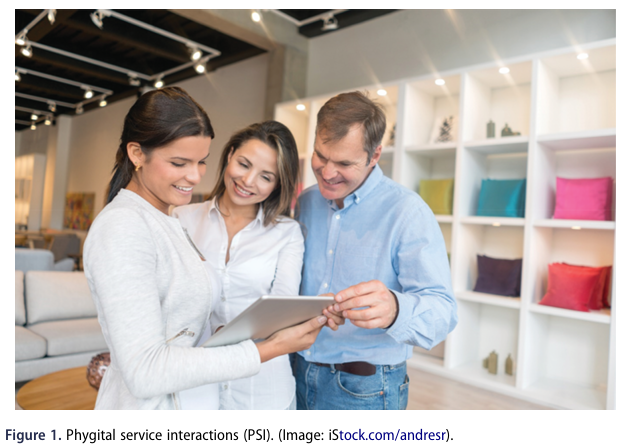

Purpose: Even as retailers add digital features to their physical stores and equip their service teams with digital devices, no research has addressed the implications of frontline employees (FLEs) sharing a screen side-by-side with customers as a contemporary service practice. This paper aims to identify the potential customer benefits of this service practice.

Design/methodology/approach: Noting the lack of theoretical considerations of screen-sharing in marketing, this paper adopts an interdisciplinary approach and combines learning theories with computer-supported collaborative learning topics to explore how screen-sharing service practices can lead to benefits or drawbacks.

Findings: The findings specify three main domains of perceived benefits and drawbacks (instrumental, social link, individual control) associated with using a screen-sharing service. These three dimensions in turn are associated with perceptions of accepted or unaccepted expertise status and relative competence.

Research limitations/implications: The interdisciplinary perspective applied to a complex new service interaction pattern produces a comprehensive framework that can be applied by services marketing literature.

Practical implications: This paper details tactics for developing appropriate training programmes for FLEs and sales teams. In omnichannel service environments, identifying and leveraging the key perceived benefits of screen-sharing can establish enviable competitive advantages for service teams.

Originality/value: By integrating findings of a qualitative research study with knowledge stemming from education sciences, this paper identifies some novel service postures (e.g. teacher, peer, facilitator) that can help maximise customer benefits.

***

Reference – (WYSIWYG-style inventory for customer experience)

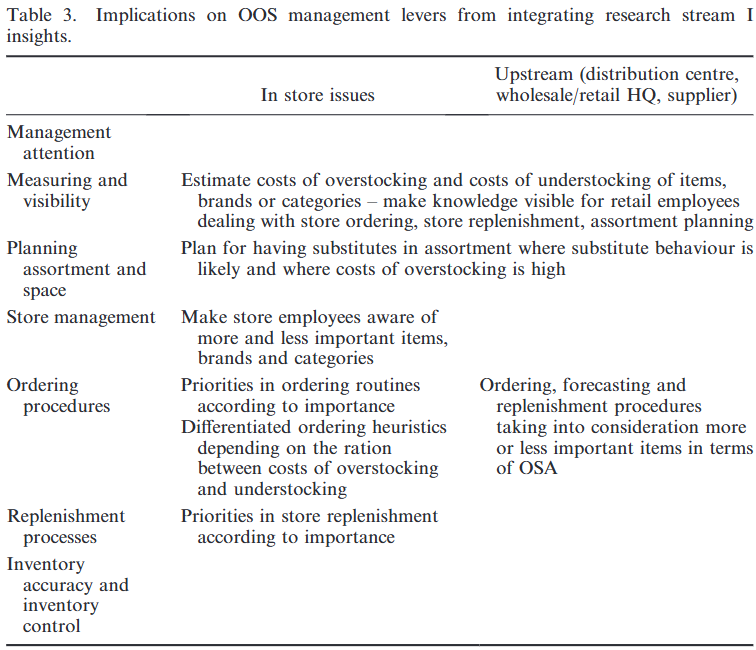

Aastrup, J., & Kotzab, H. (2010). Forty years of out-of-stock research–and shelves are still empty. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 20(1), 147-164.

This article examines 40 years of research conducted in the area of Out-of-Stocks (OOS). Two research streams originating from the Progressive Grocer (1968) study are reviewed. The first stream dealt with demand side issues and analysed consumer responses to OOS. The other dealt with supply side issues and analysed the extent and root causes of OOS situations as well as how to improve OOS. Four paradoxes are derived from the review and are discussed: 1) OOS rates largely seem to fall into an average level at about 7 to 8% despite 40 years of research; 2) only sparse attempts have been made to integrate the two research streams; 3) there is an emphasis on minimizing OOS rather than relying on basic trade-offs as addressed by Economic-Order-Quantity theory to optimize OOS levels; and 4) despite clear evidence of the store as the major contributor to OOS situations, the store has largely remained a ‘black-box’ in OOS research. Finally, the study suggests that OOS research can integrate the notions of the two streams by showing how the conditions for consumer responses can be translated into different degrees for costs of understocking taken from Economic-Order-Quantity theory. This will have important implications for the management of OOS.