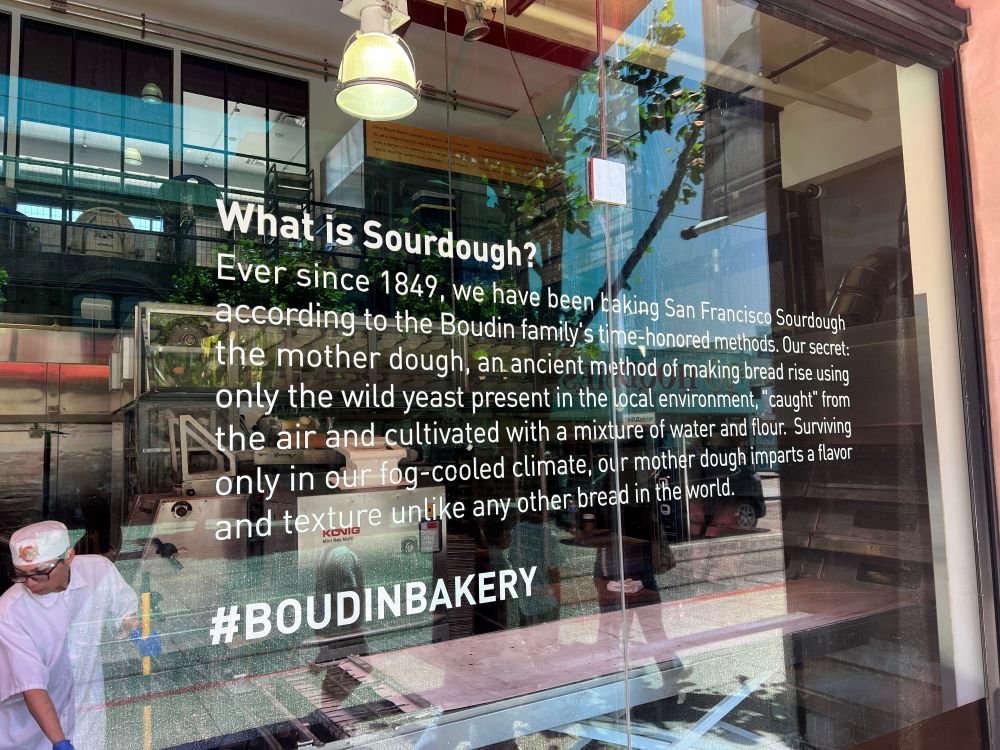

Boudin Bakery at Fisherman’s Wharf is well known for its sourdough bread. Many visitors stop by to enjoy clam chowder served in a sourdough bowl.

What is Sourdough?

Ever since 1849, we have been baking San Francisco Sourdough according to the Boudin family’s time-honored methods. Our secret: the mother dough, an ancient method of making bread rise using only the wild yeast present in the local environment, “caught” from the air and cultivated with a mixture of water and flour. Surviving only in our fog-cooled climate, our mother dough imparts a flavor and texture unlike any other bread in the world.

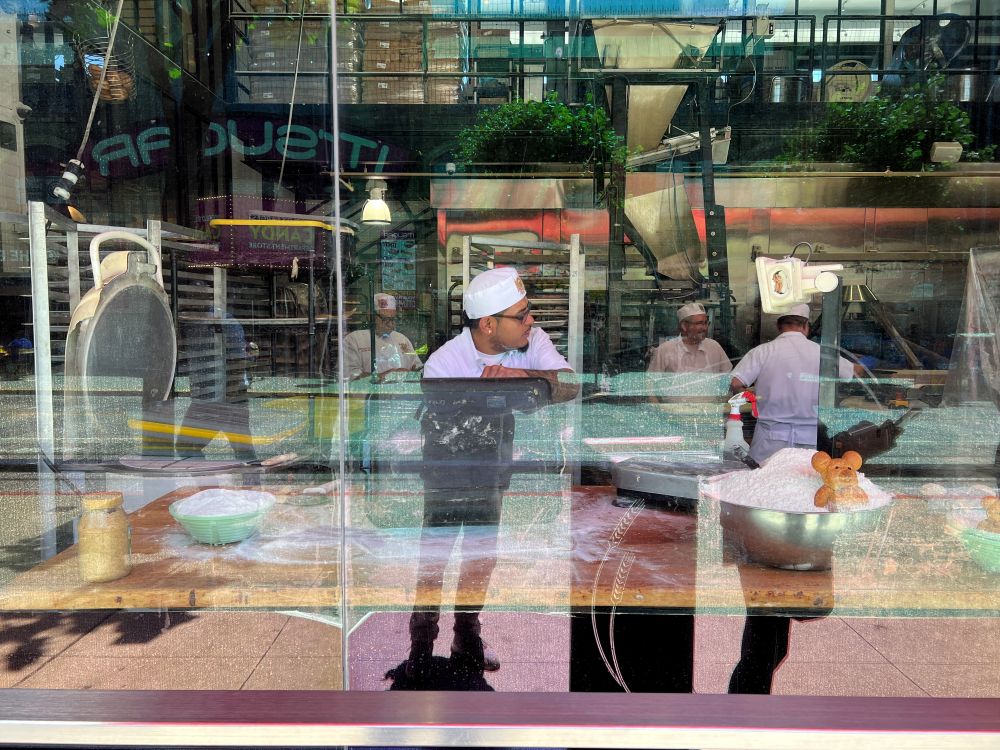

When I visited, I noticed many people were watching how the bread was made.

Inside the building, several bakers were mixing flour, shaping dough, and baking loaves behind large glass windows. Many people stood outside, quietly observing. They were interested in the process, not just the final food. I was curious about why people care about how something is made.

Usually, marketers focus on product benefits. However, consumers may pay greater attention to how a product is made. There could be two reasons. First, they may want to avoid harmful ingredients and look for safety. Second, they may want to give credit to those who work hard.

Regardless of the reasons, marketers should not focus only on product outcomes. They should also make the production process more visible and highlight the makers’ effort. Showing what happens behind the scenes can have a strong impact on how people see the product.

***

Reference 1

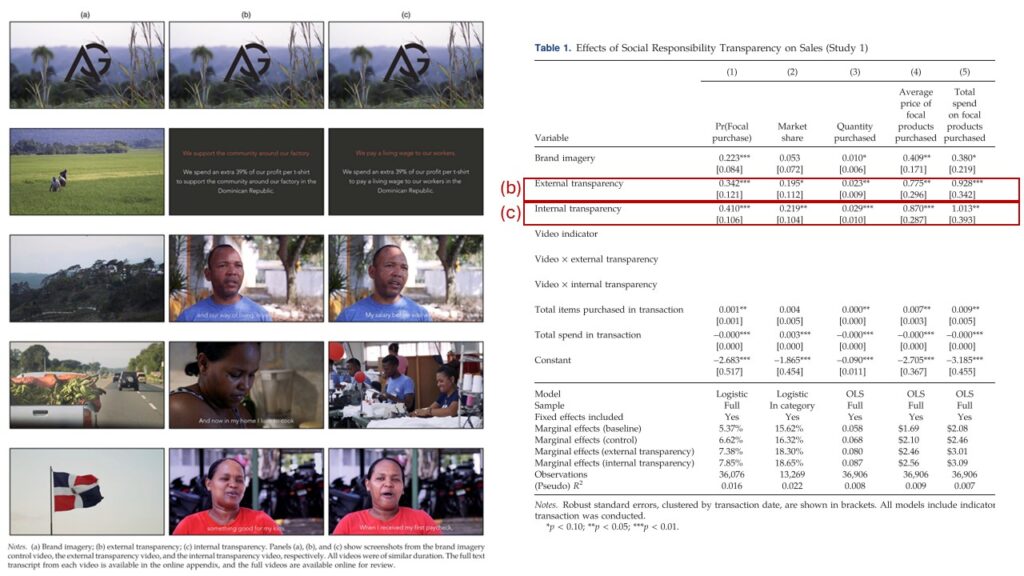

Buell, R. W., & Kalkanci, B. (2021). How transparency into internal and external responsibility initiatives influences consumer choice. Management Science, 67(2), 932–950.

Amid growing calls for transparency and social and environmental responsibility, companies are employing different strategies to improve consumer perceptions of their brands. Some pursue internal initiatives that reduce their negative social or environmental impacts through responsible operations practices (such as paying a living wage to workers or engaging in environmentally sustainable manufacturing). Others pursue external responsibility initiatives (such as philanthropy or cause-related marketing). Through two experiments conducted in the field and complementary online experiments, we compare how transparency into these internal and external initiatives affects customer perceptions and sales. We find that transparency into both internal and external responsibility initiatives tends to dominate generic brand marketing in motivating consumer purchases, supporting the view that consumers take companies’ responsibility efforts into account in their decision making. Furthermore, the results provide converging evidence that transparency into a company’s internal responsibility practices can be at least as motivating of consumer sales as transparency into its external responsibility initiatives, incrementally increasing a consumer’s probability of purchase by 6.40% and 45.85% across our two field experiments, conducted in social and environmental domains, respectively. Our results suggest that it may be in the interest of both business and society for managers to prioritize internal responsible operations initiatives to achieve both top- and bottom-line benefits while mitigating social and environmental harms.

***

Reference 2

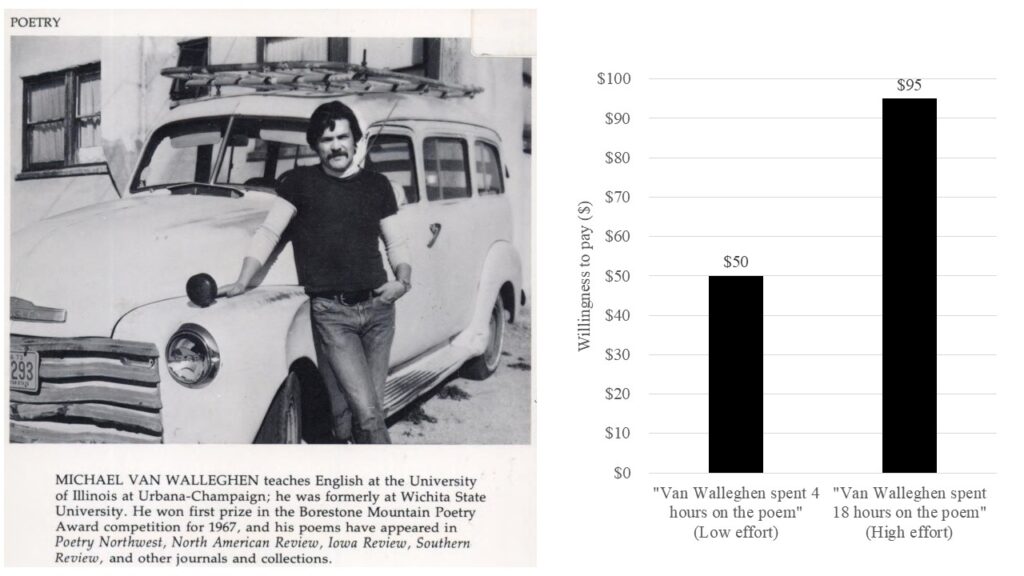

Kruger, J., Wirtz, D., Van Boven, L., & Altermatt, T. W. (2004). The effort heuristic. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(1), 91–98.

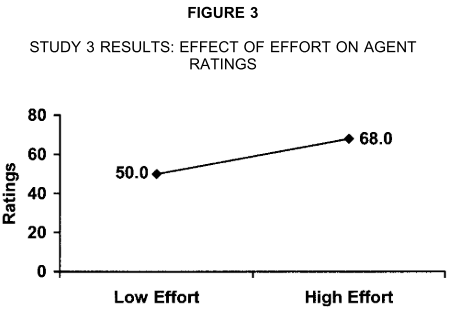

The research presented here suggests that effort is used as a heuristic for quality. Participants rating a poem (Experiment 1), a painting (Experiment 2), or a suit of armor (Experiment 3) provided higher ratings of quality, value, and liking for the work the more time and effort they thought it took to produce. Experiment 3 showed that the use of the effort heuristic, as with all heuristics, is moderated by ambiguity: Participants were more influenced by effort when the quality of the object being evaluated was difficult to ascertain. Discussion centers on the implications of the effort heuristic for everyday judgment and decision-making.

***

Reference 3

Morales, A. C. (2005). Giving firms an “E” for effort: Consumer responses to high-effort firms. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 806–812.

This research shows that consumers reward firms for extra effort. More specifically, a series of three laboratory experiments shows that when firms exert extra effort in making or displaying their products, consumers reward them by increasing their willingness to pay, store choice, and overall evaluations, even if the actual quality of the products is not improved. This rewarding process is defined broadly as general reciprocity. Consistent with attribution theory, the rewarding of generally directed effort is mediated by feelings of gratitude. When consumers infer that effort is motivated by persuasion, however, they no longer feel gratitude and do not reward high-effort firms.

***

Reference 4

Norton, M. I., Mochon, D., & Ariely, D. (2012). The “IKEA Effect”: When labor leads to love. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(3), 453–460.

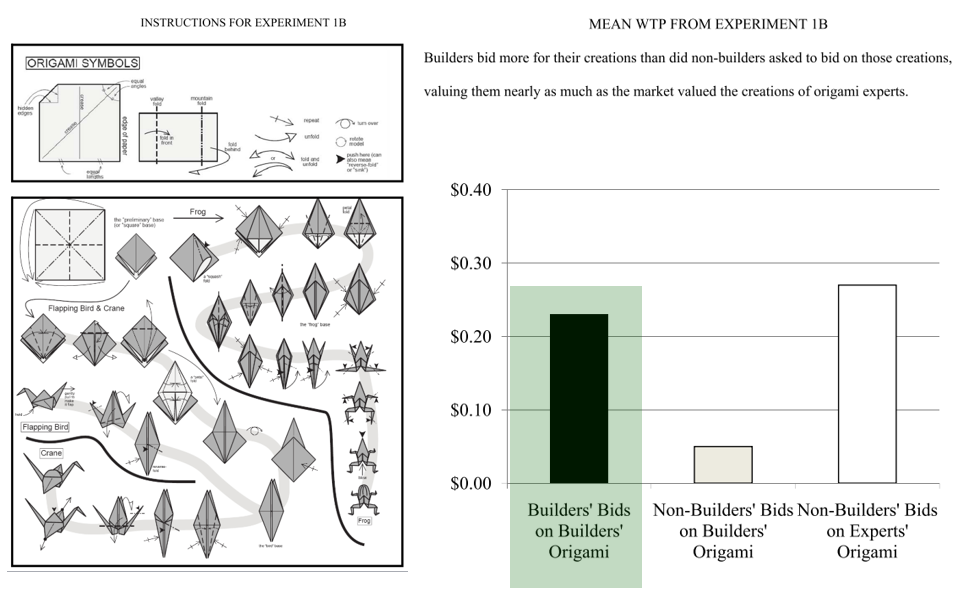

In four studies in which consumers assembled IKEA boxes, folded origami, and built sets of Legos, we demonstrate and investigate boundary conditions for the IKEA effect-the increase in valuation of self-made products. Participants saw their amateurish creations as similar in value to experts’ creations, and expected others to share their opinions. We show that labor leads to love only when labor results in successful completion of tasks; when participants built and then destroyed their creations, or failed to complete them, the IKEA effect dissipated. Finally, we show that labor increases valuation for both “do-it-yourselfers” and novices.

The article about Boudin Bakery at Fisherman’s Wharf draws attention to fascinating consumer behavior that goes beyond simply buying food. While the bakery is historically known for its distinctive sourdough bread made from a century-old “mother dough,” the article highlights something more intriguing: many visitors gathered outside large glass windows not to purchase bread, but to watch bakers mix flour, shape dough, and prepare loaves. People stood still, quietly observing every detail of the process. This scene suggests that consumers are not only interested in the final product; they are deeply drawn to how something is created. After reading the article, I began to reflect on this phenomenon more broadly and realized that I, too, often engage in similar behavior.

For example, when I scroll through social media, I frequently pause to watch videos of cooking, sewing, pottery making, woodworking, and DIY projects. Even when I have no intention of cooking that dish or making that craft myself, I still find the process deeply satisfying to watch. These videos are often relaxing, aesthetically pleasing, and surprisingly addictive. This personal experience made me even more curious about the behavior described in the article. Why do people, including myself, enjoy watching the process of something being made, even when the final product is not the main focus?

The article proposes two possible explanations that resonate with current consumer trends. First, observing a production process can function as a form of safety assurance. In a world where concerns about ingredients, hygiene, and ethical production are increasing, watching a product being made provides transparency. Seeing bakers handle dough openly or watching chefs prepare food in front of customers reduces uncertainty and helps consumers trust the product more. Transparency serves as evidence that nothing harmful or hidden is happening behind closed doors.

Second, watching a production process can increase appreciation of effort and craftsmanship. When consumers witness the physical labor, skill, and time invested into making something—whether it is bread, handmade clothing, or a piece of furniture—they develop greater admiration for the creators. This appreciation can create emotional attachment and a sense of authenticity that industrial mass production often lacks. In this way, the process itself becomes part of the product’s value.

Beyond the article’s explanations, my own experiences suggest an additional possibility: people may enjoy watching making-process videos simply because they are inherently satisfying and psychologically rewarding. The rhythmic movements, clear transformations (such as dough rising or fabric taking shape), and predictable sequences found in these videos can be pleasing to watch, similar to ASMR or “slow TV.” The process offers a sense of progress and completion, which may be calming or gratifying even when viewers are passive observers.

As consumers increasingly spend time watching behind-the-scenes content, cooking videos, crafting tutorials, and live production processes, marketers and researchers need to understand the underlying motivations for this behavior. The phenomenon is no longer limited to artisanal bakeries like Boudin; it is widespread across social media and modern retail environments. Therefore, the question becomes both relevant and necessary: Why do people like to watch the process of something being made? Exploring this question can offer valuable insight into consumer psychology, process transparency, and the emotional and cognitive benefits of observing creation.

The author explains that many consumers today care not only about the final product but also about how that product is made. This interest often comes from two main motivations: the desire to avoid harmful ingredients and ensure safety, and the desire to acknowledge and appreciate the effort of workers behind the scenes. The research further demonstrates that transparency into internal and external responsibility initiatives significantly influences consumer choice. I agree with the author’s argument and would like to provide two real-world examples that illustrate this point.

The first example is the Japanese omakase restaurant. Omakase means “I’ll leave it up to you,” representing a strong sense of trust between the customer and the chef. Customers sit at the counter and observe the chef preparing each dish in real time. This setup allows them to see the freshness of the ingredients, the chef’s craftsmanship, and the careful attention given to each step. The transparency of the cooking process not only enhances trust but also elevates the dining experience, giving it a luxurious and exclusive feeling. This is one of the reasons why people willingly choose omakase restaurants, even though they are often very expensive.

The second example is the Lotus Silk Product Shops in Inle, Myanmar. Visitors—both locals and foreigners—appreciate the beauty of the lotus silk scarves, clothing, bags, and other crafts, but they are equally fascinated by the production process. They can watch artisans extract fibers from lotus stems, twist them into threads, dye them, and weave them into fabric. Seeing the complexity and effort involved gives customers a deeper sense of authenticity, specialty, and value. In this case as well, transparency in the production process increases appreciation and strengthens the consumer’s overall experience.