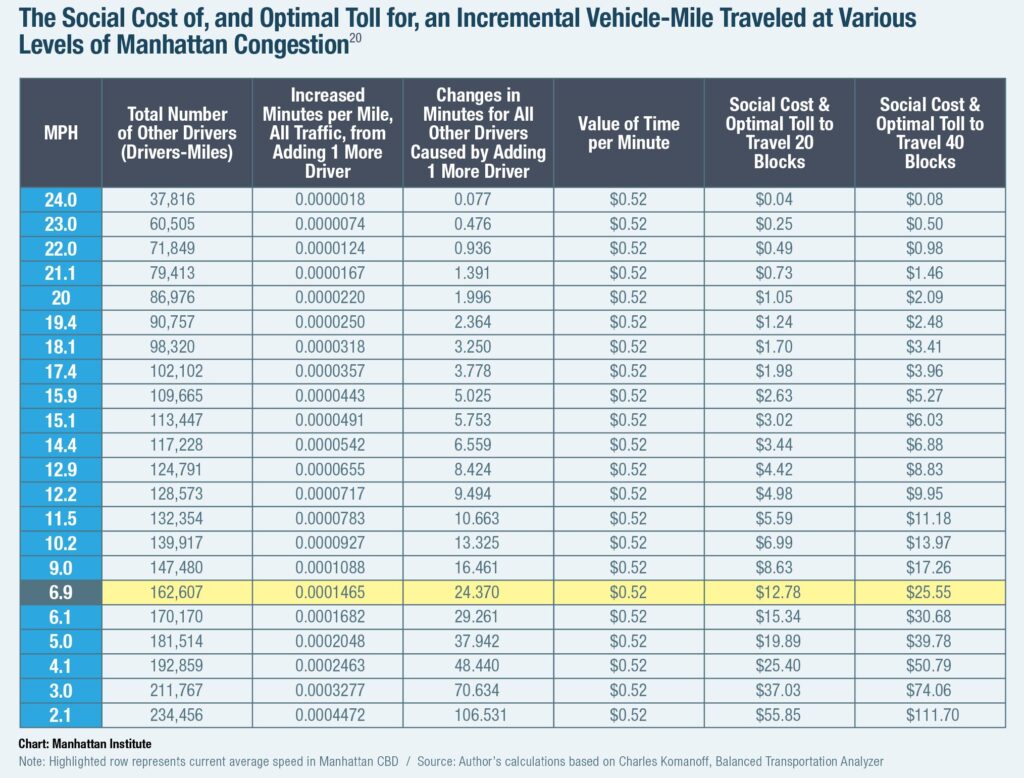

A recent drive on an express lane showed tolls as high as $9 to Broadway and $10 to I-380, depending on the real-time traffic conditions. The price for using the same road is not predetermined but decided on the spot.

Dynamic tolls or congestion pricing may adjust based on traffic volume, creating an anchor for drivers to evaluate the value of the express lane. If traffic is heavy, the higher toll can feel worth it when compared to the frustration of sitting in congestion.

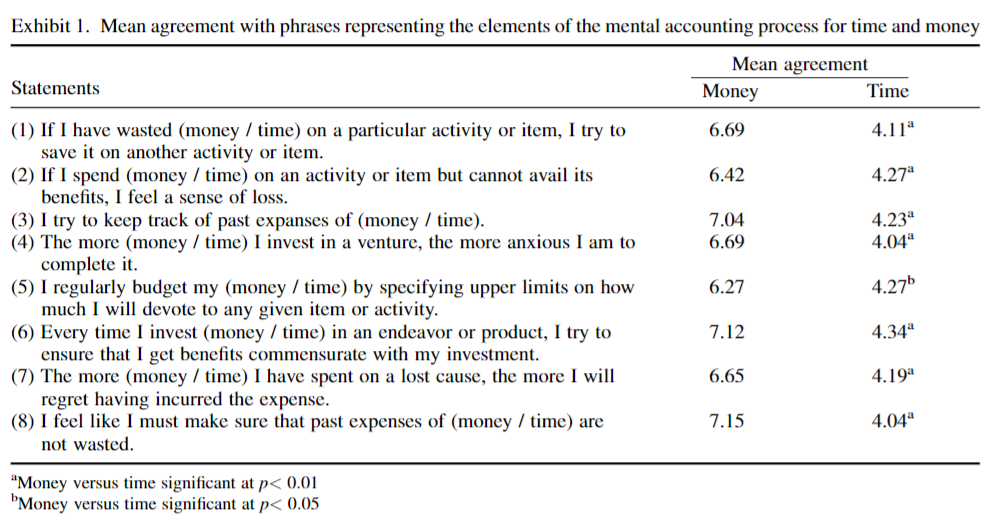

Mental accounting, the tendency to categorize resources such as money and time, is a key principle at work. The price is not just about the toll but about the potential loss of time stuck in traffic. During a stressful commute, paying $10 to save several minutes is appealing. The system uses behavioral cues to nudge drivers into seeing the express lane as a valuable, time-saving option. This differentiated road pricing taps into our varying perceptions of time.

***

Reference

Soman, D. (2001). The mental accounting of sunk time costs: Why time is not like money. Journal of behavioral decision making, 14(3), 169-185.

The sunk-cost effect, an irrational attention to non-recoverable past costs while making current decisions, has been documented widely in the domain of monetary costs. In this paper, I study the effect of past time investments on current decisions. In three experiments using choice situations, I demonstrate that the sunk-cost effect is not observed for past investments of time, but the effect reappears when the investments are expressed as monetary quantities. I further propose that this ‘pseudo-rationality’ is due to the fact that individuals lack the ability to account for time in the same way as they account for money. In two additional experiments, I facilitate the accounting of time and show that the irrational sunk-cost effect reappears. In a final experiment, I test my propositions in a setting where subjects make real investments of time and subsequently make real choices.