It is Election Day, and these photos capture an intriguing scene for those who may wonder how American students engage in voting. Here, a line of students stretches out the door, each person waiting patiently to cast their vote—a sight that demonstrates just how seriously these young adults take their role in shaping the future.

Yet, some students saw the long queue ahead questioned: “Does my vote really matter?” and “Do I really make a difference?” These sentiments resonate with many, reflecting the common struggle between civic duty and individual doubt.

Ultimately, these snapshots remind me that, despite geographical and cultural differences, the act of voting holds a universal significance. Whether here in Stanford or in Korea, each vote really matters, which is why it is essential to inspire people to visit the voting centers and participate in the electoral process.

***

Reference

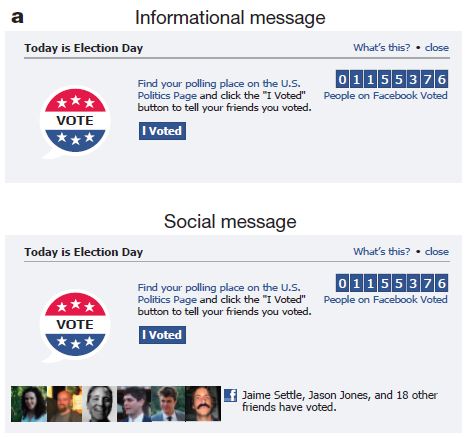

Bond, Robert M., Christopher J. Fariss, Jason J. Jones, Adam D. I. Kramer, Cameron Marlow, Jaime E. Settle, and James H. Fowler (2012), “A 61-Million-Person Experiment in Social Influence and Politicial Mobilization,” Nature, 489, 295-298.

Human behaviour is thought to spread through face-to-face social networks, but it is difficult to identify social influence effects in observational studies, and it is unknown whether online social networks operate in the same way. Here we report results from a randomized controlled trial of political mobilization messages delivered to 61 million Facebook users during the 2010 US congressional elections. The results show that the messages directly influenced political self-expression, information seeking and real-world voting behaviour of millions of people. Furthermore, the messages not only influenced the users who received them but also the users’ friends, and friends of friends. The effect of social transmission on real-world voting was greater than the direct effect of the messages themselves, and nearly all the transmission occurred between ‘close friends’ who were more likely to have a face-to-face relationship. These results suggest that strong ties are instrumental for spreading both online and real-world behaviour in human social networks.