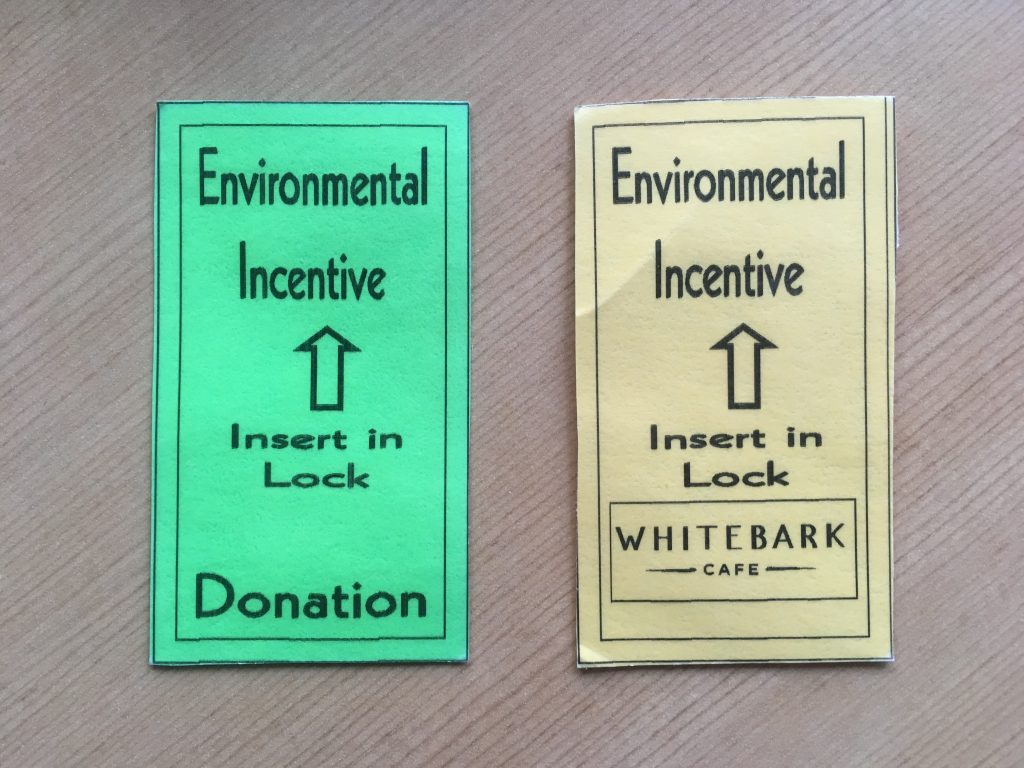

Banff Aspen Lodge has an interesting environmental incentive program. If guests stay two or more nights and prefer no housekeeping service in this hotel, it offers a choice of options for the guest’s consideration:

- Option 1: The hotel will make a donation of $4 on behalf of guests to the Banff Community Foundation, which supports environmental initiatives in their community. To select this option, guests insert the Green Card into the entry door lock.

- Option 2: Enjoy one complimentary beverage at the Whitebark Cafe, which is located in the lobby. To select this option, guests insert the Yellow Card into the entry door lock. A complimentary beverage coupon is delivered to the guest’s room.

I suspect someone carefully designed a choice architecture with a psychological intervention to nudge guests to choose “No” housekeeping service. This program will be effective because…

- Three options are provided (housekeeping vs. environmental 1 vs. environmental 2). It differs from the choice architecture commonly observed in the behavioral economics in which two competing options are provided. Having three options may relieve the guests’ burden, which decreases their intentions to defer choices.

- Only two environmental options are highlighted. As guests read and think about “how” to protect environment, the chance they select one of the two environmental options may increase.

- Two environmental options reflect the two motivations why people should behave environmentally friendly; helping others (charitable giving) and helping themselves (economic incentive).

- Finally, when guests select one environmental option, they do not speak or write down but simply insert a card into their own entry door lock. This simple behavior has no peer pressure.

This environmental incentive program might be more effective than making a commitment at check-in, a scientifically proven intervention in the prior marketing paper.

***

Reference

Baca-Motes, K., Brown, A., Gneezy, A., Keenan, E. A., & Nelson, L. D. (2012). Commitment and Behavior Change: Evidence from the Field. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5), 1070–1084.

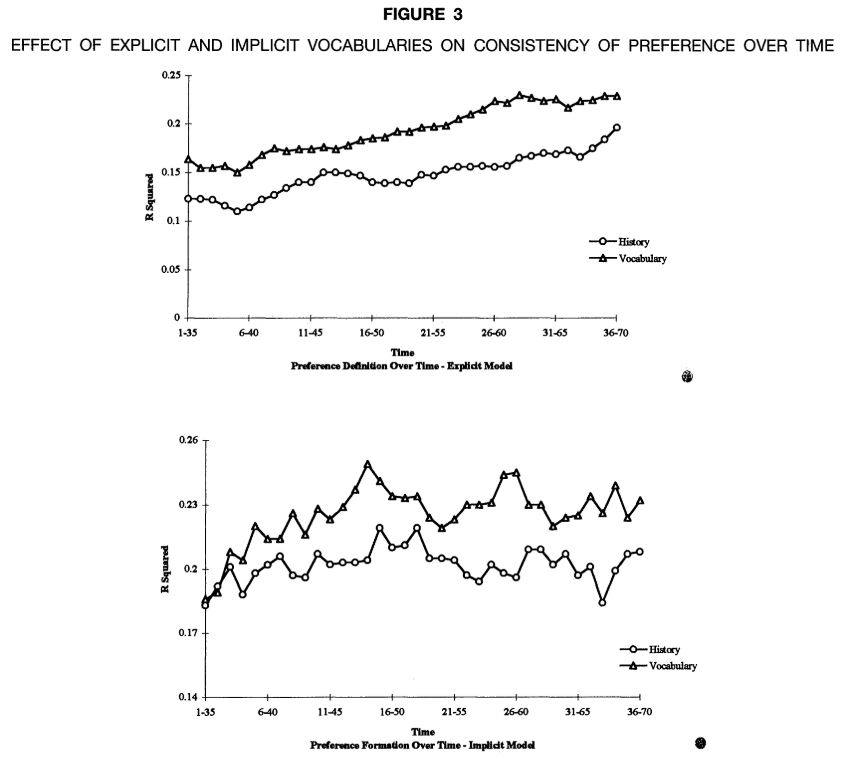

Influencing behavior change is an ongoing challenge in psychology, economics, and consumer behavior research. Building on previous work on commitment, self-signaling, and the principle of consistency, a large, intensive field experiment (N = 2,416) examined the effect of hotel guests’ commitment to practice environmentally friendly behavior during their stay. Notably, commitment was symbolic—guests were unaware of the experiment and of the fact that their behavior would be monitored, which allowed them to exist in anonymity and behave as they wish. When guests made a brief but specific commitment at check-in, and received a lapel pin to symbolize their commitment, they were over 25% more likely to hang at least one towel for reuse, and this increased the total number of towels hung by over 40%. This research highlights how a small, carefully planned intervention can have a significant impact on behavior. Theoretical and practical implications for motivating desired behavior are discussed.