When I visited the Santa Cruz Wharf for the Woodies on the Wharf event, I saw a funny sign. It said:

Husband Daycare

Need time to yourself?

Need time to just relax?

Leave your husband with us!

Drop off as early as 6am Pick up at 3pm

This place is not a real daycare but a fishing and motorboat rental shop. Many men come here to enjoy fishing all day. But the sign is written for wives who could leave their husbands here and enjoy free time.

The same event, men fishing, can have two opposite meanings. One story is “men go fishing to have fun.” Another story is “wives get peace while husbands are at daycare.” Like Tom Sawyer convincing others to paint a fence for him, the value of fishing trip is constructed.

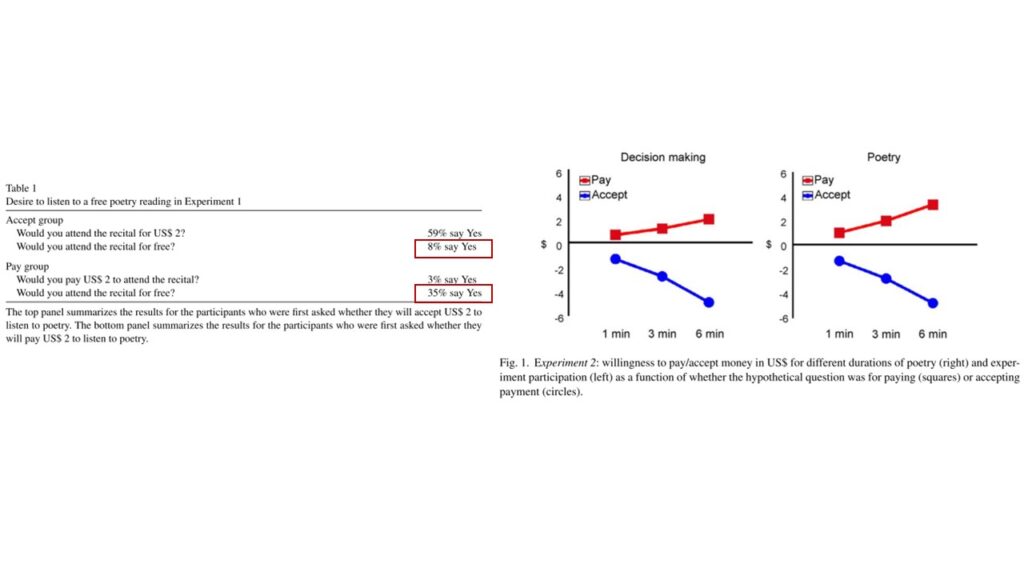

This idea was explained by a classic experimental study in which students were asked if they would attend a poetry recital for free. But before this, they received different questions. One group was first asked if they would attend to receive $2 (accept group). The other group was first asked if they would attend by paying $2 (pay group). Later, when both were asked if they would attend for free, only 8% of the accept group said yes, while 35% of the pay group said yes. This shows that value depends on how the event is framed.

We do not know the real value of an experience. Sometimes, we create that value based on the story we tell others.

***

Reference

Ariely, D., Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (2006). Tom Sawyer and the construction of value. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 60(1), 1-10.

This paper challenges the common assumption that economic agents know their tastes. After reviewing previous research showing that valuation of ordinary products and experiences can be manipulated by non-normative cues, we present three studies showing that in some cases people do not have a pre-existing sense of whether an experience is good or bad-even when they have experienced a sample of it.