I was recently invited to speak at the Duncan Anderson Design Lecture Series, hosted by Professor Wesley Woelfel at the Department of Design, California State University, Long Beach. Unlike my previous virtual talk, this time I traveled to Long Beach and delivered the lecture in person.

My presentation focused on an ongoing collaborative research project with Nayoung Yoon at Aalto University and Wonseok Choi at Project Rent. Nayoung contributes perspectives of brand managers and consumers and Wonseok provides practical knowledge gained from launching over 200 pop-up stores throughout Seoul.

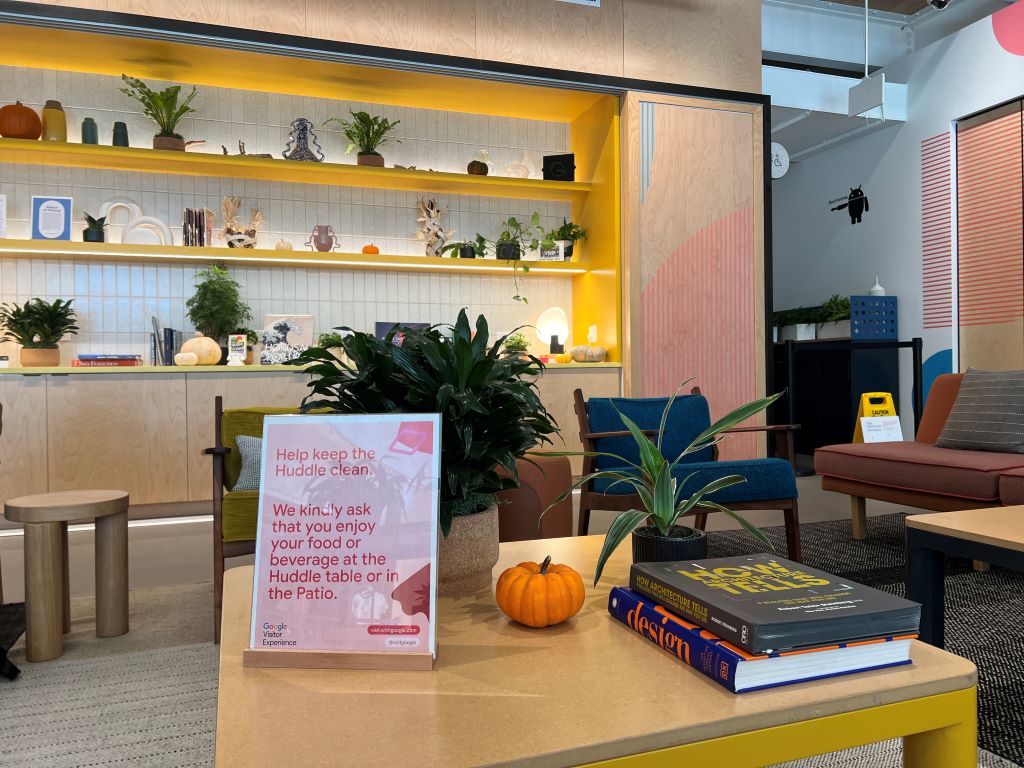

The lecture began with three landmark cases including Simmons Grocery Store. Following this, I presented four recent pop-up stores operated by Project Rent, each carefully designed around unique goals. Among them was the Ghana Chocolate House, an innovative pop-up store reshaping brand perception.

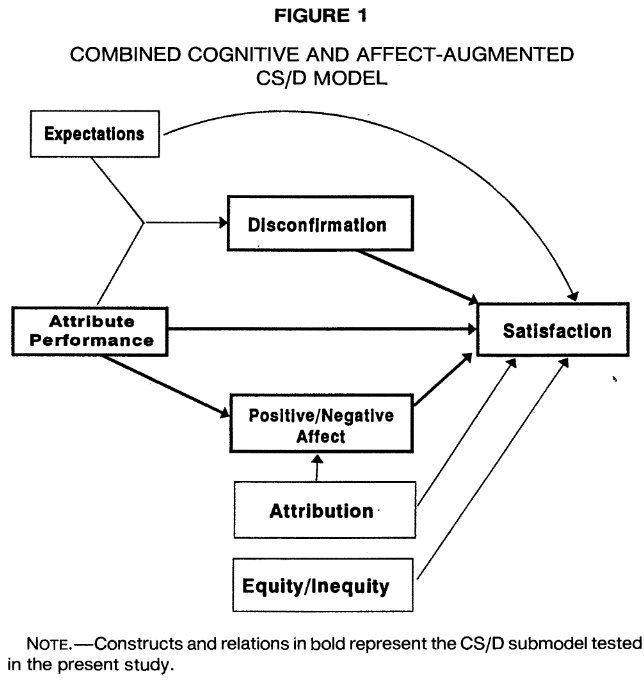

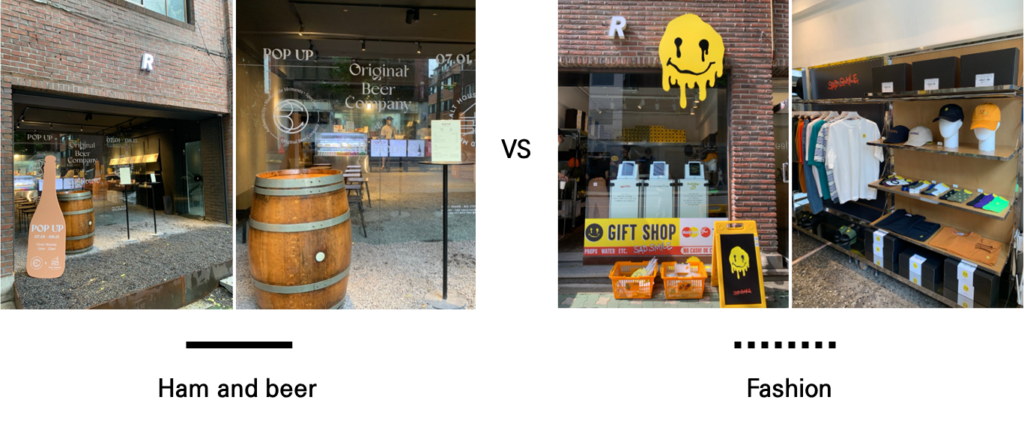

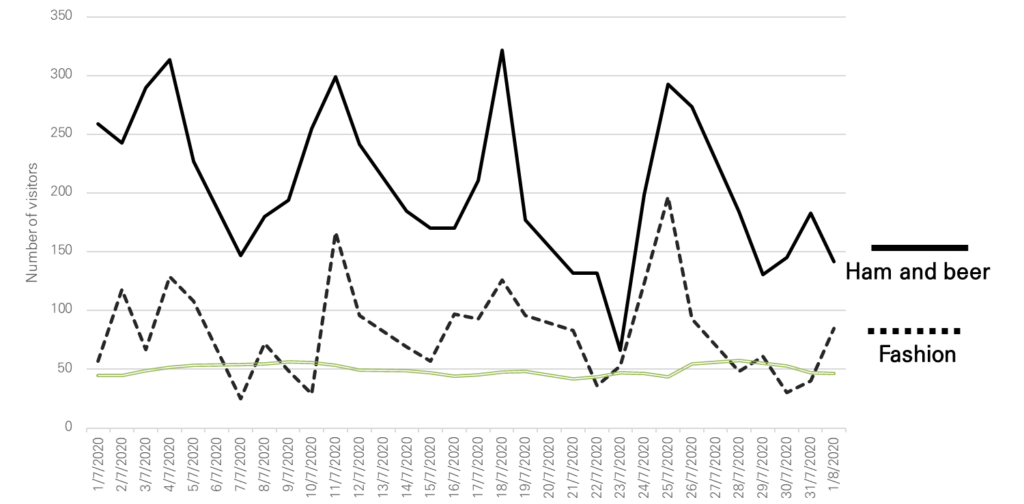

The audience paid attention to not only cases but also numbers. To illustrate this, I shared preliminary findings from data we collected during July 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in Seoul. The graph shows daily visitor counts for two pop-up stores, a ham and beer pop-up (solid line) and a fashion pop-up (dotted line), alongside daily COVID-19 case numbers (green line). During pandemic restrictions, the food and beverage pop-up consistently attracted more visitors than the fashion pop-up when operating. These findings, highlighting the appeal of experiential consumption, were presented by Nayoung in 2024.

We need to provide further insights into how brands can leverage pop-up stores.

***

Reference

Yoon, N., & Joo, J. (2024). Experience matters when not restricted: The impact of product type and COVID-19 restrictions on pop-up store visits. Proceedings of the European Marketing Academy, 53rd, (119359)

By taking empirics-first research approach, we study the effect of product type and COVID-19 restrictions on pop-up store visits. This quasi-experimental study uses store traffic and store-entry ratios of four pop-up stores displaying different product types (i.e., experience goods or search goods) at varying times (before or after the COVID-19 restrictions). Our research shows that pop-up store visits were higher when a store displayed experience goods than search goods before the COVID-19 restrictions. However, the store visits to experience goods pop-up stores plummeted after the imposition of restrictions, higher than search goods, suggesting the restrictions’ stronger detrimental effect on experience goods. Our findings advance research on consumer behavior relating to pop-up store products and the impact of mobility restrictions on store visits.