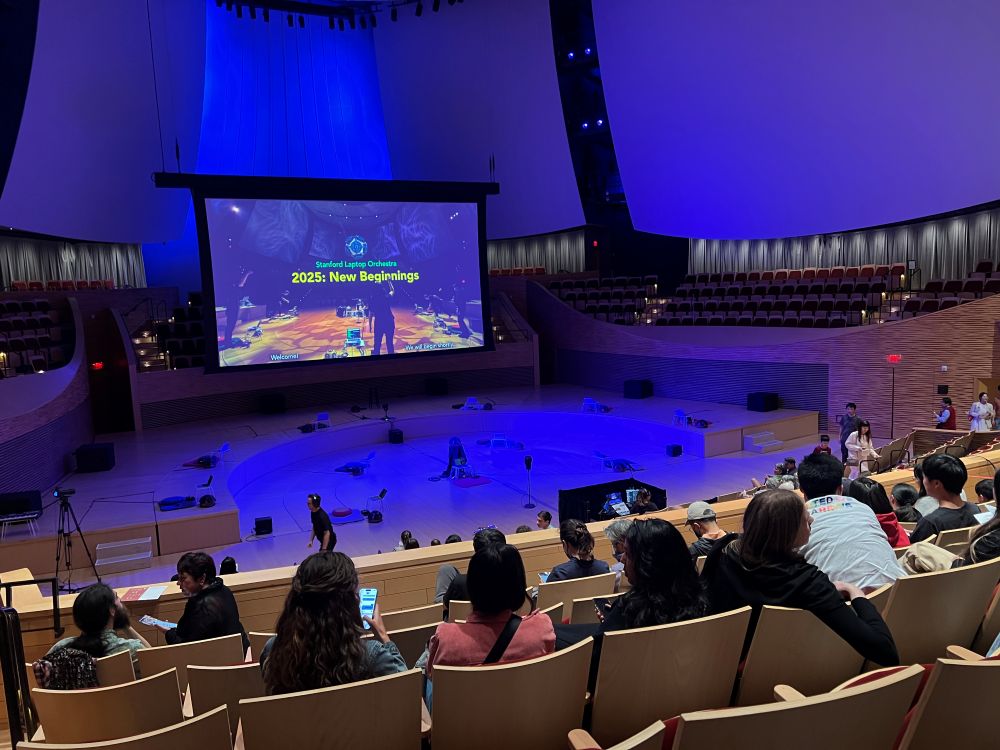

At Stanford University’s Bing Concert Hall, I experienced a performance by SLOrk, the Stanford Laptop Orchestra. Instead of traditional instruments like piano or violin, students used laptops, software, and motion-sensitive controllers. They sat on cushions arranged in a circle, manipulating sound with gestures and code.

I listened most attentively to one piece titled Bay Area Rain. It was inspired by memories of rainstorms. The music was chaotic and captured the feeling of rain.

What surprised me was not sound itself. The performers moved slowly, sometimes standing, sometimes kneeling. The lighting changed from purple to red. Everything was outside of what I imagined a concert to be.

I thought music made by computers could not have emotion. But after the concert, I felt strangely awake. The performance did not fit into any known category, yet powerful.

***

Reference

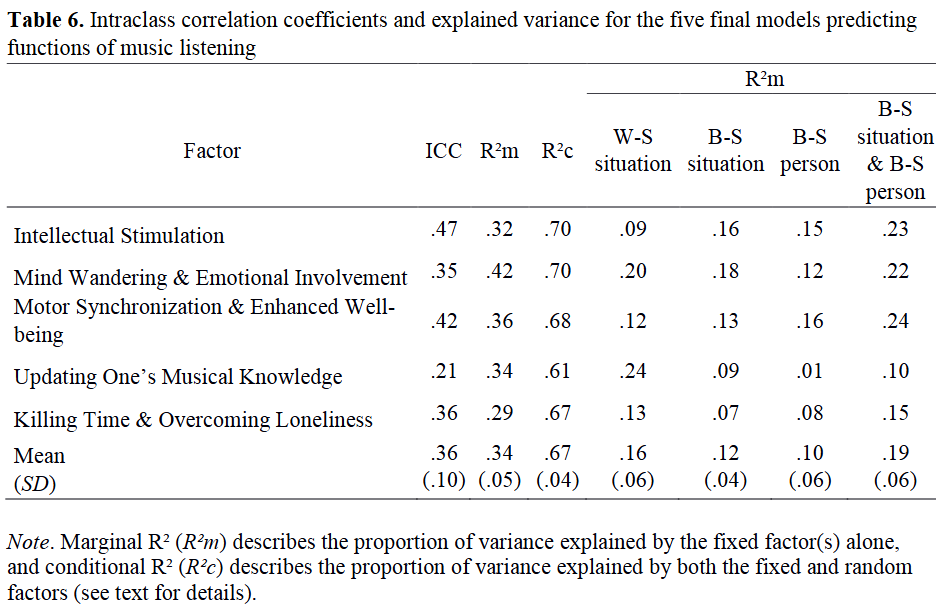

Greb, F., Schlotz, W., & Steffens, J. (2018). Personal and situational influences on the functions of music listening. Psychology of Music, 46(6), 763-794.

On the one hand, the majority of research on the functions of music listening focuses on individual differences; on the other hand, a growing amount of research investigates situational influences. However, the question of how much of our daily engagement with music is attributable to individual characteristics and how much it depends on the situation is still under-researched. To answer this question and to reveal the most important predictors of the two domains, participants (n = 587) of an online study reported on questions regarding the situation, the music, and the functions of music listening for three self-selected situations. Additionally, multiple person-related variables were measured. Results revealed that the influence of individual and situational variables on the functions of music listening varied across functions. The influence of situational variables on the functions of music listening outweighed the influence of individual characteristics. On the situational level, main activity while listening to music showed the greatest impact, while on the individual level, intensity of music preference was most influential. Our findings suggest that research on music in everyday life should incorporate both – individual and situational – variables determining the complex behavior of people interacting with music in a certain situation.