I once believed mini-mes are expensive because they are produced by cutting edge 3D printers, which differ from my 3D printer or a mere 3D food printer. A news article elaborates that human miniatures are not cheap.

Pinla3D scans its customers in-store and then gives them a choice of 3D model sizes. A 25cm (9.8-inch) figure costs RMB 3,580 (US$580), according to the store’s site. Three generations of one family can be immortalized in plastic at 1:9 scale for RMB 8,997 (US$1,470). That’s cheaper than we’ve seen it done by a Japanese startup site – with the added bonus that going in-person to the store will make the mini-me more accurate than submitting a bunch of photos to a website.

However, my belief was corrected when I visited Tianzifang in Shanghai, China. A series of mini-mes displayed outside a store cost only RMB 480 (US$ 68). I wondered how and why they are inexpensive.

The mystery was solved when I entered the store. These mini-mes were not produced by 3D printers. Instead, two people made mini-mes out of clay.

We tend to assign greater value to a product when it is made by human than when made by machine. It is called as “handmade effect.” Then, why did I observe a reverse handmade effect, that it, hand-crafted mini-mes are cheaper than the ones printed by 3D printers? I suspect the handmade effect is observed only when the people who make a product is clearly associated with the final product. If the association is not established so that buyers do not know who produce their purchased products, handmade effect disappears and buyers are not willing to pay more. If I come back to Shanghai, I suggest two mini-me makers to give their own name cards and personal stories to buyers!

***

Reference

Fuchs, C., Schreier, M., & van Osselaer, S. M. J. (2015). The Handmade Effect: What’s Love Got to Do with It? Journal of Marketing, 79(2), 98–110.

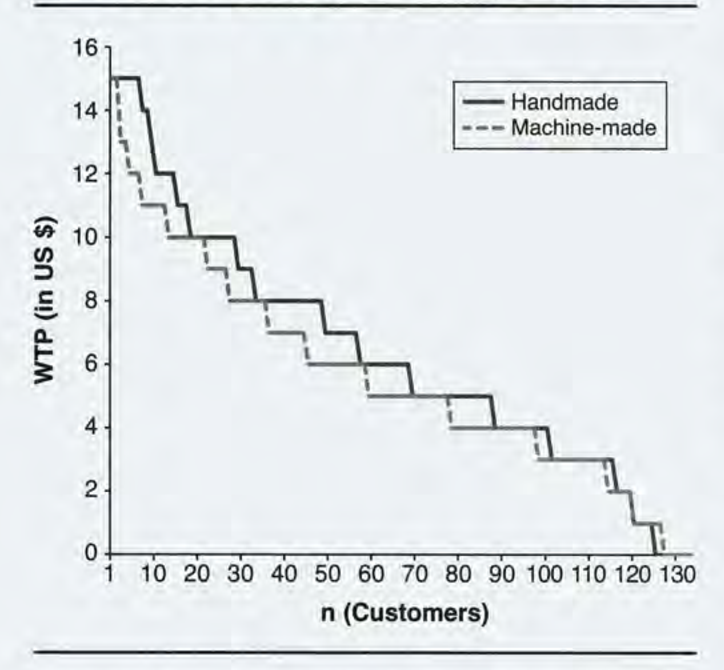

Despite the popularity and high quality of machine-made products, handmade products have not disappeared, even in product categories in which machinal production is common. The authors present the first systematic set of studies exploring whether and how stated production mode (handmade vs. machine-made) affects product attractiveness. Four studies provide evidence for the existence of a positive handmade effect on product attractiveness. This effect is, to an important extent, driven by perceptions that handmade products symbolically “contain love.” The authors validate this love account by controlling for alternative value drivers of handmade production (effort, product quality, uniqueness, authenticity, and pride). The handmade effect is moderated by two factors that affect the value of love. Specifically, consumers indicate stronger purchase intentions for handmade than machine-made products when buying gifts for their loved ones but not for more distant gift recipients, and they pay more for handmade gifts when purchased to convey love than simply to acquire the best-performing product.