Recently, I visited the Google Visitor Experience at the Googlplex. I went in expecting something amazing—maybe the chance to try out new techonolgy like self driving cars (like Waymo), virtual reality glasses (like Ray-Ban Meta Glasses), or advanced AI assistants (like Open AI). High expectations felt natural—it is Silicon Valley and Google, the place for extraordinary experiences.

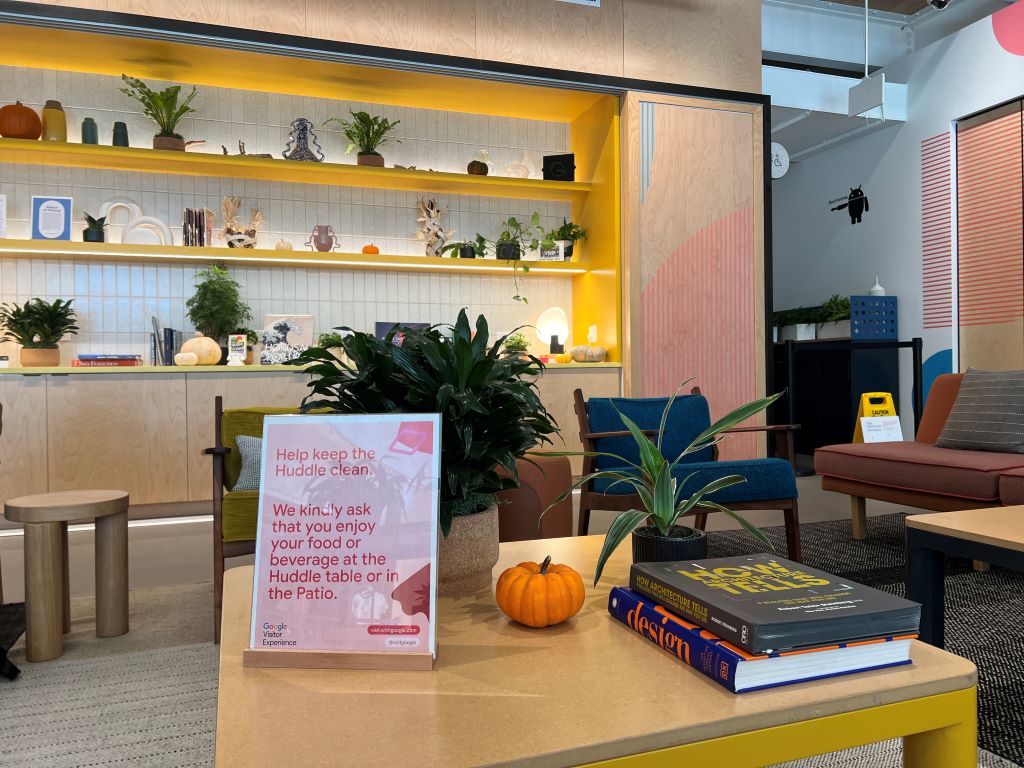

However, the reality was much simpler. The space named as “Google Visitor Experience” revolves around three main activities: browsing Google-branded merchandise in the store, enjoying a coffee at the café, and relaxing in a small public area called “Huddle.”

These activities felt quite ordinary, which was surprising. For me, and probably for many people in Asia, the word “experience” suggests something special—sophisticated and luxurious. But here at Google Visitor Experience, what I found was simplicity instead. This gap between what I expected and what I actually encountered made me think about the meaning of “experience.”

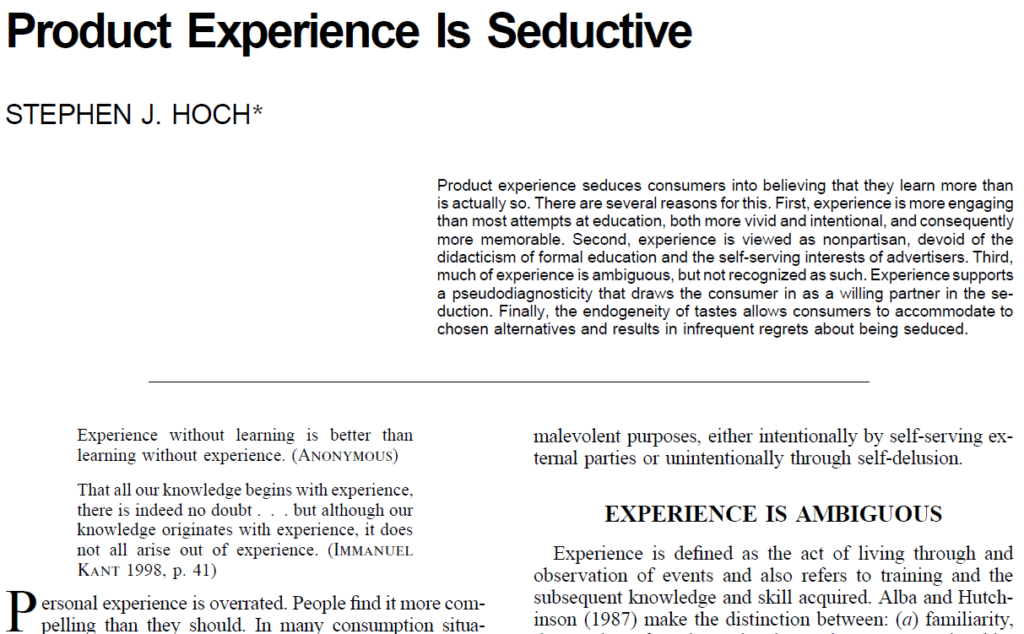

In consumer research, “experience” is hard to define and measure. Hoch (2002) points out that experiences is enticing but tricky to pin down, which often makes studying them less precise. My visit to the Google Visitor Experience reminded me that sometimes our expectations for an “experience” can be bigger than reality. This visit made me think more about how we define experiences.

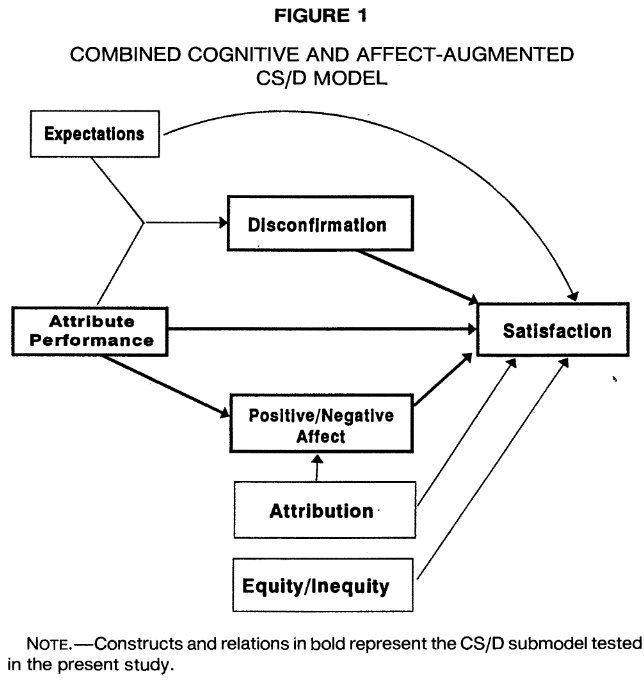

Now may be the time to define “experience” through the lens of satisfaction research suggested by Oliver (2014). Customer satisfaction hinges on the gap between expectation and reality, and experience should be understood in the same way—by studying both the anticipated and actual experience. A key challenge here will be managing experience expectations, similar to how we approach expectation management for satisfaction.

***

Reference

Hoch, S. J. (2002). Product experience is seductive. Journal of consumer research, 29(3), 448-454.

Product experience seduces consumers into believing that they learn more than is actually so. There are several reasons for this. First, experience is more engaging than most attempts at education, both more vivid and intentional, and consequently more memorable. Second, experience is viewed as nonpartisan, devoid of the didacticism of formal education and the self-serving interests of advertisers. Third, much of experience is ambiguous, but not recognized as such. Experience supports a pseudodiagnosticity that draws the consumer in as a willing partner in the seduction. Finally, the endogeneity of tastes allows consumers to accommodate to chosen alternatives and results in infrequent regrets about being seduced.

***

Reference

Oliver, R. L. (1993). Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. Journal of consumer research, 20(3), 418-430.

An attempt to extend current thinking on postpurchase response to include attribute satisfaction and dissatisfaction as separate determinants not fully reflected in either cognitive (i.e., expectancy disconfirmation) or affective paradigms is presented. In separate studies of automobile satisfaction and satisfaction with course instruction, respondents provided the nature of emotional experience, disconfirmation perceptions, and separate attribute satisfaction and dissatisfaction judgments. Analysis confirmed the disconfirmation effect and the effects of separate dimensions of positive and negative affect and also suggested a multidimensional structure to the affect dimensions. Additionally, attribute satisfaction and dissatisfaction were significantly related to positive and negative affect, respectively, and to overall satisfaction. It is suggested that all dimensions tested are needed for a full accounting of postpurchase responses in usage.