I recently visited Zentis Osaka and discovered a lesson in experience design hidden behind the door marked “Room 001.”

The typical hotel laundry room is a purely utilitarian space, equipped only with the essentials: washers, dryers, and an iron.

Zentis, however, focused not just on the chore itself, but on how guests spend time while waiting. They transformed the often-dreary waiting area into an unexpected, welcoming third place.

This space is like a residential lounge. It has rich leather chairs, a comfortable sofa, and a table. A bookshelf with selected books is there. Also, a premium coffee machine offers fresh coffee.

This hotel recognized the fundamental gap between laundry as a necessary chore and hospitality as a comprehensive experience. By intentionally elevating a mundane task, they turned the waiting time into a moment of relaxation.

***

Reference

Baek, J., & Choe, Y. (2025). Detrimental Impact of Waiting on Dining Experiences: Evidence from Online Restaurant Reviews. Asia Marketing Journal, 27(1), 39-47.

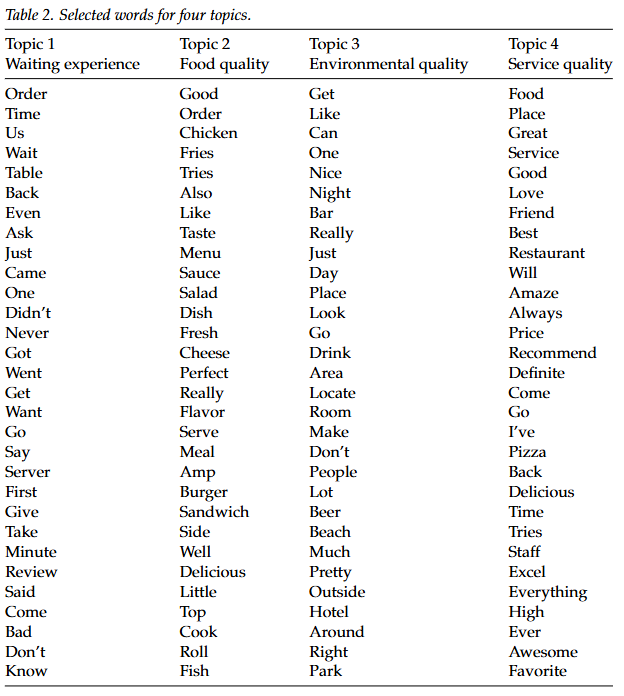

This study employs big data analytics to examine customers’ waiting experiences in restaurants, a critical component of the broader hospitality and tourism industry. Drawing upon a large corpus of online reviews, the analysis uses topic modeling to identify four salient themes that emerge—waiting, food, servicescape, and service quality—informing the way in which customers perceive and evaluate dining experiences. Two subsequent regression analyses reveal a significant negative relationship between waiting-related comments and overall review ratings, underscoring the disproportionate influence of waiting experiences in shaping customer satisfaction. These findings offer valuable insights for hospitality and tourism practitioners and researchers aiming to deepen their understanding of how waiting times and experiences can impact service perceptions and overall consumer evaluations in restaurant contexts.

The laundromat case at Zentis Osaka can be seen as an example of experience design that reconfigures the time spent waiting for laundry through spatial design. While most hotel laundry rooms focus only on functional efficiency, Zentis designed its laundry space as a lounge, allowing guests to perceive waiting time as a moment of rest. This approach does more than improve the user experience; it also brings strategic benefits to the hotel. Laundry is a service touchpoint where dissatisfaction can easily arise, yet Zentis transforms it into a distinctive experience, reducing negative perceptions and strengthening positive memories of the hotel.

This case interprets waiting as a physical experience that occurs during the laundry process—the time guests spend waiting for a cycle to finish. The refined and minimal design of the space aims to make this waiting time more comfortable. Rather than filling the area with various activities, the hotel provides a simple and calm environment, allowing guests to stay without feeling pressure to “do something.” This approach felt closely aligned with a design thinking perspective, as it redefines the problem not as laundry itself but as the discomfort experienced during the waiting process and addresses it through spatial experience.

However, this case led me to question whether laundry in a hotel context should truly be understood as an experience of waiting. Hotels are places where travelers temporarily stay and rest, often while exploring unfamiliar environments. In reality, many guests do not remain in the laundry room while their clothes are washing. Instead, they return to their rooms, organize photos from the trip, eat a meal, or walk around the neighborhood. From this perspective, the issue of hotel laundry is less about the length of waiting time and more about how the act of laundry itself is perceived.

In particular, doing laundry while traveling is perceived differently from everyday laundry. Language barriers, uncertainty about usage, and unfamiliar layouts make laundry an object of cognitive burden. The discomfort comes not from the duration of the process, but from hesitation and anxiety during the decision-making stage—whether to do laundry at all, where to do it, and how to do it.

This perspective originates from my own experience in Tokyo. During a long stay at an APA business hotel, laundry gradually became necessary, yet using an outside laundromat felt intimidating due to language and system barriers. While visiting the hotel’s large public bath on the top floor, I noticed washing machines located nearby with clear English instructions. I realized that I could complete laundry while bathing, returned to my room, brought my laundry, and finished both activities naturally within the same time frame.

>>https://www3.apahotel.com/hotel/syutoken/tokyo/tokyoojima/ <<

What made this experience comfortable was not that waiting itself was enjoyable, but that the cognitive burden of deciding how to do laundry was significantly reduced. By integrating laundry into an existing activity flow, laundry became a natural choice rather than a problem requiring deliberate effort. In this sense, the APA hotel case brought to mind the concept of nudge theory, as it subtly guided behavior by embedding laundry into an existing routine rather than explicitly instructing users.

From this comparison, Zentis and APA hotels address the same issue through different approaches. Zentis reconstructs the waiting time itself as an experience, while APA integrates laundry into existing activities so that it does not stand out as a separate task. Although neither removes waiting entirely, both succeed in preventing users from perceiving it as a problem.

Therefore, while I acknowledge the Zentis case as a strong example of redesigning waiting time, I believe that in a hotel context, laundry should also be interpreted through the lens of cognitive burden rather than waiting alone. For travelers, laundry is not a matter of how to spend time, but a matter of deciding whether and how to act. In this sense, customer experience design in hotels can be extended beyond enhancing waiting moments to supporting effortless decision-making.