At Prague, Czech Republic, visitors experienced riding a new tram called T3 Coupe in virtual reality.

The T3 tram is an iconic component of the Prague city scape. In collaboration with Anna Marešová designers, the Prague Public Transit Co. has created a new pleasure tram concept based on the tradition of the Tatra T3 tram, putting this legendary vehicle in an entirely new context while respecting its authentic looks. By opening the rear of the tram and combining original elements with modern technologies, the project has given rise to an old-timer that demonstrates how even public transit can deliver real luxury. Because the tram has only one set of doors, it’s been dubbed the T3 Coupé. This special tram preserves the romance of the 1960s and is a tribute to the designer of the original Tatra T3 tram – František Kardaus (1908–1986). The new T3 Coupé tram hits the streets in autumn 2018.

They sit on the chairs, wore Samsung Gear VR headset, and watched a 360 degree video as passengers. A driver and other passengers appeared in the video.

Before having enjoyed the virtual tram, I asked a lady about what is T3 Coupe, where to sit, and how to start the device. Interestingly, this human interaction made my non-real experience more real. It was ironic that I was more immersed into the virtual world because of my experiencing language barrier; she could not explain to me about T3 Coupe in English and I could not understand any Czech written on the ticket.

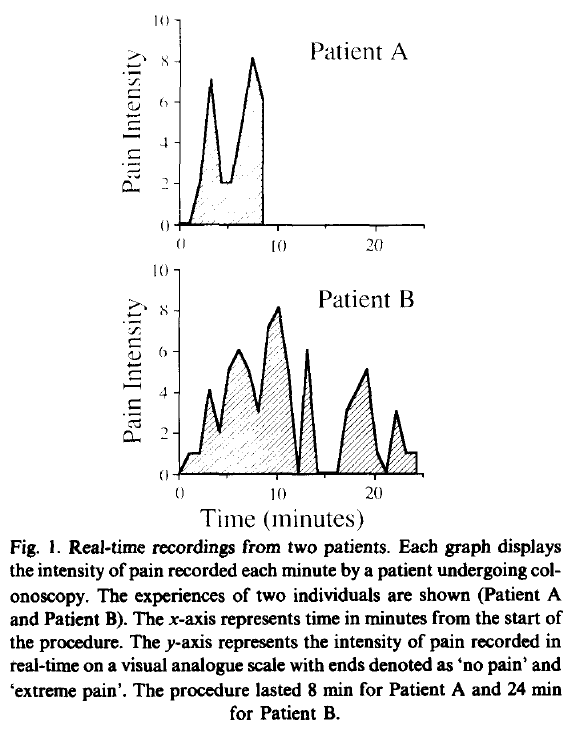

Peak end rule is probably one of the most well established psychological heuristic. Kahneman and his colleagues (1993) found that people tend to judge an experience based on how they felt at its peak and at its end. However, people might consider its beginning as well when the experience is virtual. Virtual experience might need to be carefully wrapped up by its beginning, its peak, and its end.

***

Reference

Kahneman, D., Fredrickson, B. L., Schreiber, C. A., & Redelmeier, D. A. (1993). When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End. Psychological Science, 4(6), 401–405.

Subjects were exposed to two aversive experiences: in the short trial, they immersed one hand in water at 14 °C for 60 s; in the long trial, they immersed the other hand at 14 °C for 60 s, then kept the hand in the water 30 s longer as the temperature of the water was gradually raised to 15 °C, still painful but distinctly less so for most subjects. Subjects were later given a choice of which trial to repeat. A significant majority chose to repeat the long trial, apparently preferring more pain over less. The results add to other evidence suggesting that duration plays a small role in retrospective evaluations of aversive experiences; such evaluations are often dominated by the discomfort at the worst and at the final moments of episodes.

One thought on “Language barrier makes virtual reality more real”