Most urban dwellers want authentic, natural goods. Unfortunately, growing plants or baking breads requires a significant amount of effort. Therefore, they often buy artificial ones instead.

Many artificial products are delicately crafted. I am often confused between an artificial product with a real one. See the two following pictures. The one above is the the real frozen beer in the plastic cup, and the one below is the artificial beer in the glass available at the Kirin Ichiban popup store.

In general, artificial products look too good to me. For example, artificial plants are cleanly green, artificial breads are beautifully baked, and artificial beers have a just right amount of foam. The more we are exposed to these perfectly beautiful artificial products, the more we will enjoy the visually best moment of each product and ignore the amount of effort to invest to enjoy it. Artificial products may lead people to discount the value of effort or labor, which is contrary to effort heuristic or IKEA effect.

**

Reference 1

Morales, A. C. (2005). Giving firms an “E” for effort: Consumer responses to high-effort firms. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 806–812.

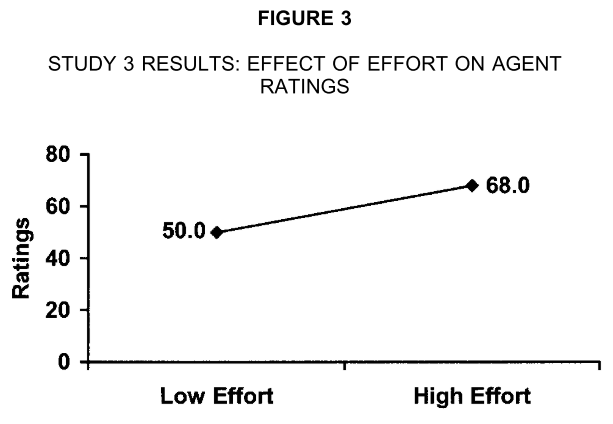

This research shows that consumers reward firms for extra effort. More specifically, a series of three laboratory experiments shows that when firms exert extra effort in making or displaying their products, consumers reward them by increasing their willingness to pay, store choice, and overall evaluations, even if the actual quality of the products is not improved. This rewarding process is defined broadly as general reciprocity. Consistent with attribution theory, the rewarding of generally directed effort is mediated by feelings of gratitude. When consumers infer that effort is motivated by persuasion, however, they no longer feel gratitude and do not reward high-effort firms.

**

Reference 2

Norton, M. I., Mochon, D., & Ariely, D. (2012). The “IKEA Effect”: When labor leads to love. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(3), 453–460.

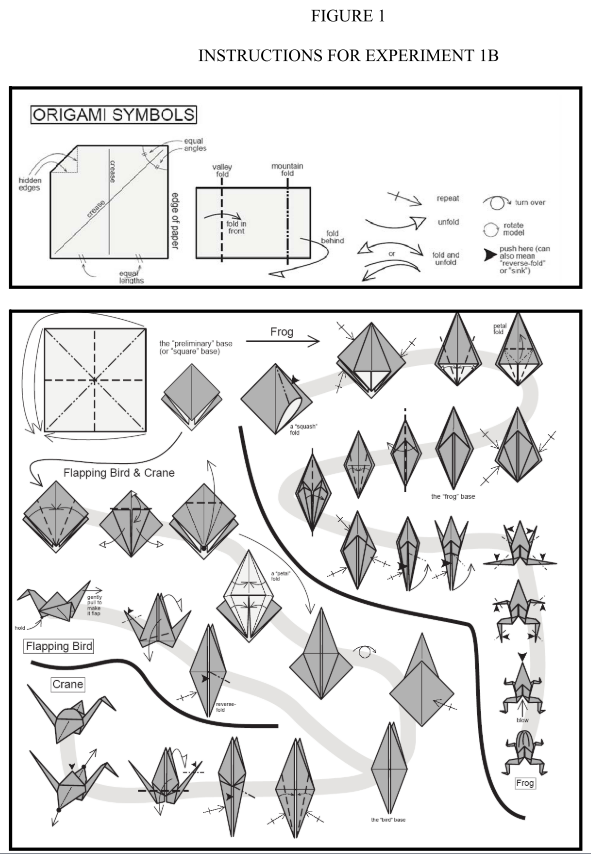

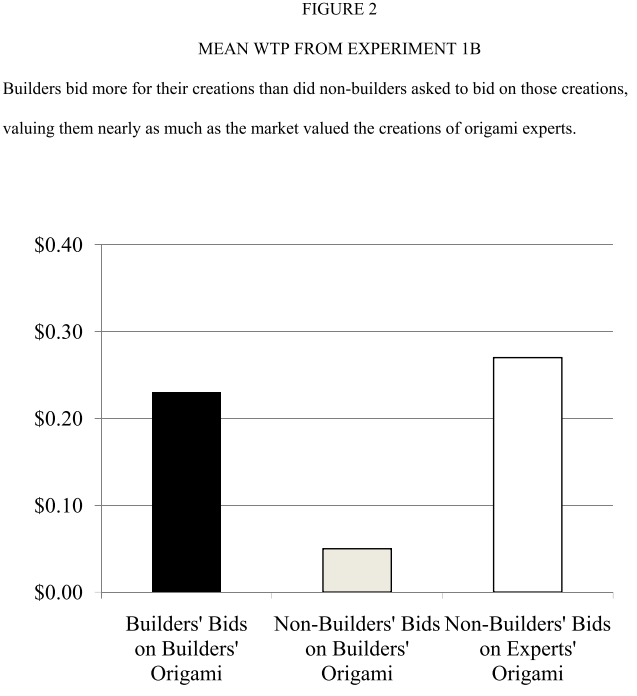

In four studies in which consumers assembled IKEA boxes, folded origami, and built sets of Legos, we demonstrate and investigate boundary conditions for the IKEA effect-the increase in valuation of self-made products. Participants saw their amateurish creations as similar in value to experts’ creations, and expected others to share their opinions. We show that labor leads to love only when labor results in successful completion of tasks; when participants built and then destroyed their creations, or failed to complete them, the IKEA effect dissipated. Finally, we show that labor increases valuation for both “do-it-yourselfers” and novices.